8½ (1963).

Whenever a filmmaker is asked, ‘what is the greatest film ever made about film making?’, invariably one of the most common answers is Federico Fellini’s 1963 Masterpiece 8½. The reason for this is that it explores the very thing that most creative people are most troubled with – creative block. Where does inspiration come from? How is it shaped? How does it translate from something vague and undefinable and blossom into something inspiring to so many others? These are big and nebulous questions, yet they are fundamental to the art that we all love. They act as the starting point for Fellini with the search for inspiration becoming the inspiration itself.

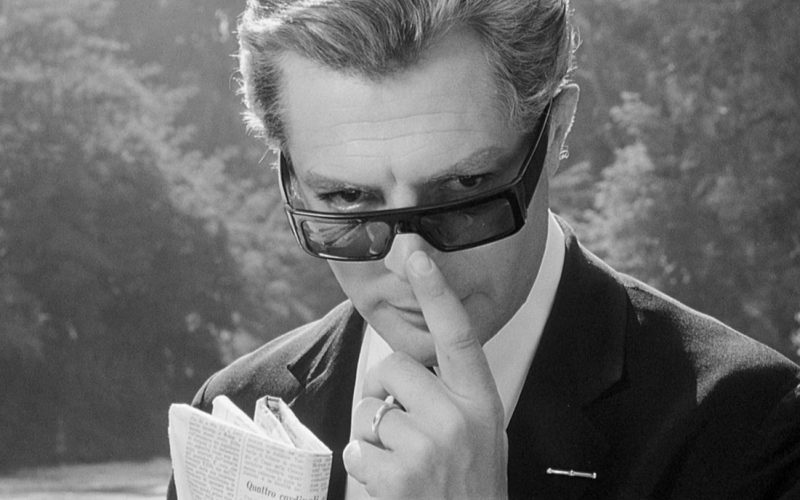

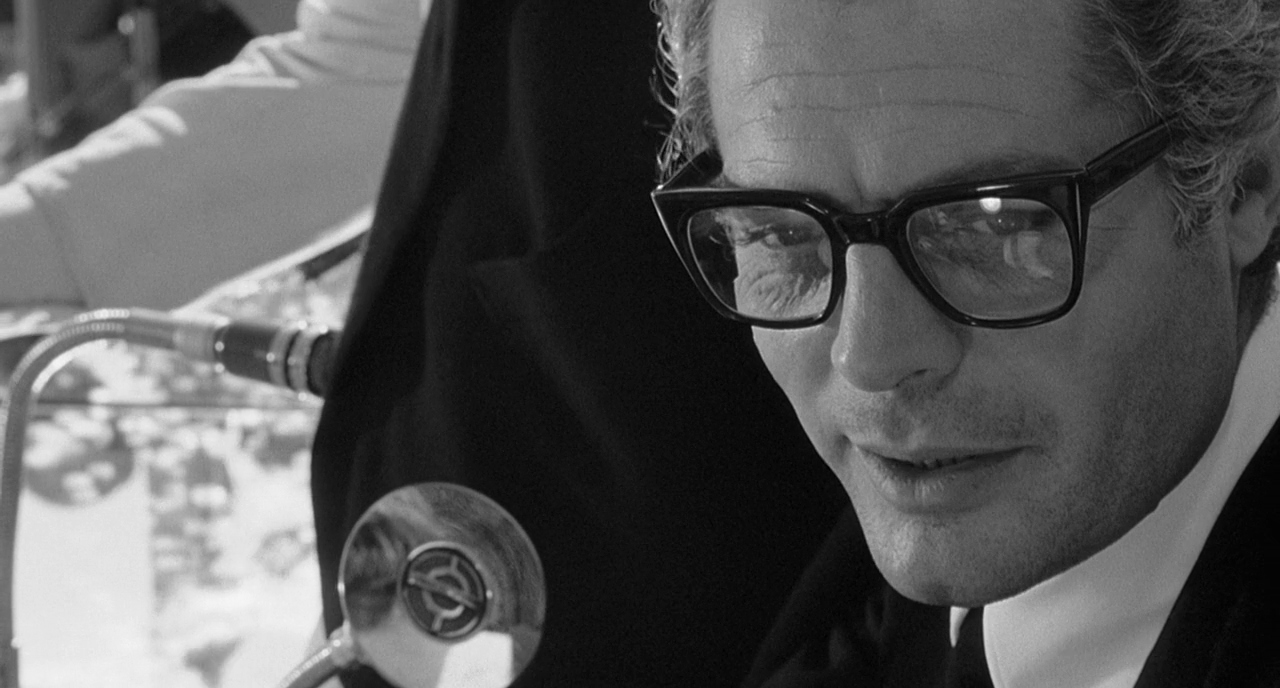

8½ is about filmmaker Guido Anselmi, played by Marcello Mastroianni, who is grappling with creativity as he attempts to begin work on a new film. He has writer’s block, a crisis of confidence, a tangled love life and a multitude of different personalities – writers, actors, producers, friends – all asking for help, input and guidance. Unfortunately, what they are looking for is what Guido is looking for in himself.

These feelings were actually the feelings of the director, Federico Felllini who, struggling to find the subject matter for his new film, turned the struggle into the film itself. It is a film about creativity and the process of making a film with Mastroianni playing the surrogate role of Fellini.

Such subject matter is deeply personal and can only be made into a very personal film, a glimpse into the mind of someone exposing his insecurities to the world. We see his dreams, an idealised childhood, the complicated relationship with his parents and the feelings of shame and guilt that his Catholic teachers made him feel after his first exposure to sexuality and the female form. Like the creative mind it regards, it’s a film that moves freely between reality and fantasy. The opening scene starts seemingly with the mundane – a load of cars parked on a ferry, their occupants looking bored and disinterested. But then suddenly Guido’s car begins to fill with smoke. He kicks the windows, calling for help. The other passengers however, just look on, some staring intently and others almost impassively. He escapes and starts to fly, there is string around his ankle and someone tries to drag him down, he tries to pull the string off but ends up falling to the ground. It is of course a dream, but it perfectly encapsulates Guido’s frustrations and worries about failure and the need to express himself freely.

Throughout the film Guido is continually being pulled left and right. He can’t give the people what they want and neither can they give him what he needs. “Happiness consists of being able to tell the truth without hurting anyone” he says. Unfortunately, with all the pressures coming from so many different sides, this dream of happiness may just remain a dream for the time being.

His biggest problem however is that he doesn’t know exactly what he wants. He has an idealised vision in the form of Claudia Cardinale but that seems to be as far as he can get. She is his muse yet he wants to be inspired more than he actually is and the ideal that Cardinale represents is as ephemeral as everything else he is looking for.

When Fellini made 8½ he was coming off the huge success of La Dolce Vita, a film that marked his movement from neo-realism to a style of film making that can only be described as Felliniesque (the title itself refers to the fact that it was Fellini’s eighth and a half film – he had previously directed seven films and had contributed to one other). It seems that he was having trouble defining what this new approach was to be, so he creates something which becomes a stroke of genius – he turns this struggle into the film itself. He even anticipates his critics to this approach when his writer states “the film [is] a series of complete senseless episodes [that] doesn’t have the advantage of the avant-garde films, although it has all of the drawbacks.”

8½ has been described as one of the greatest films about film making ever made and whilst I would suggest this could be true, it is not the first film to chronicle the making of a film focusing on the method and sometimes the madness of the process. Dziga Vertov’s 1929 film, Man With a Movie Camera may hold this distinction. In 2002 writer Charlie Kaufman and director Spike Jonze used the same process in his film Adaptation starring Nicolas Cage (playing two different brothers) and Meryl Streep. The difference however, was that 8½ is a not artifice, a coat hanger to prop up a fictionalised story – it really is the dramatised version of the creative process.

A beautiful and quite mesmerising film, 8½ is energetic, poetic, amusing and above all, very entertaining. The performances are spot on, especially Mastroianni who could have played it all dour and depressing but instead captures the characters angst with a light touch that makes him very attractive, despite his travails. The photography is stunning and the technique is spot on.

The only thing that could have made it perfect, especially in the ‘art imitating life imitating art’ way, is if it’s IMDb rating were 8.5. Instead it has to do with an 8.1.

Film ‘89 Verdict – 9/10