The ‘Burbs (1989).

Most of us, if we live anywhere long enough, will get to know our neighbours, discovering quirks and idiosyncrasies that only become noticeable if you get to know them well enough or spy on them for long enough. Joe Dante’s 1989 comedy The ‘Burbs is a film about both of these things.

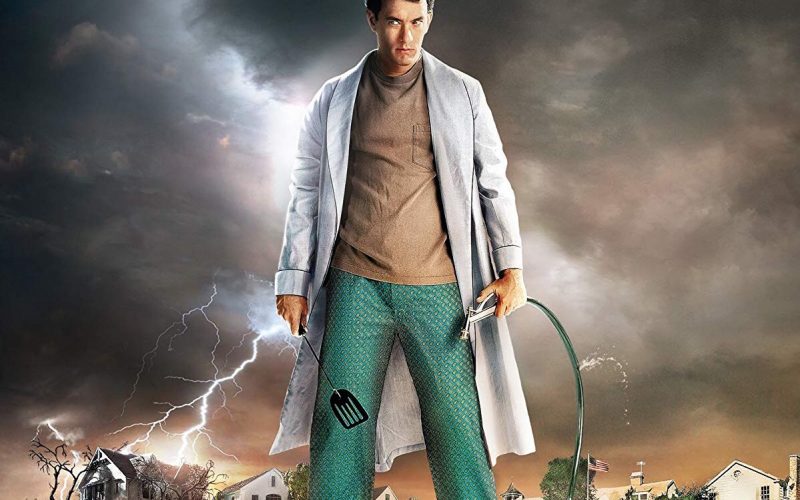

Tom Hanks, in one of his earlier roles before his ascendence from star to superstar in the early ‘90s, plays Ray Peterson, a man who wants nothing more than to spend his summer vacation pottering around the house, doing very little, watching the world go by. His wife, Carol (played by the late, great Carrie Fisher), understands that for her, the week is doomed and wants to get away to the country, but Ray is determined in his sedentary agenda.

Ray dreams of a quiet week but there are forces at play that will prevent this – his neighbours. Firstly there’s Art Weingartner (Rick Ducommun), the man child. Art is a bit of a bully, a loud mouth and day dreamer. You have to wonder what he does for a living to be able to afford to live in such a cosy cul-de-sac. We are introduced to him as he sneaks through a bush with a BB Gun, trying to dispatch some crows (in typical Art fashion, he misses). Luckily for Art, his wife is away – for now at least.

Then there’s Mark Rumsfeld (Bruce Dern), an ex-soldier who has retired to suburbia with his American flag and trophy wife Bonnie (Wendy Schaal, one of a plethora of Joe Dante regulars in front of and behind the camera). In his mind, Rumsfeld is still in the armed forces, and now lives a rather incongruous life in the suburban militia.

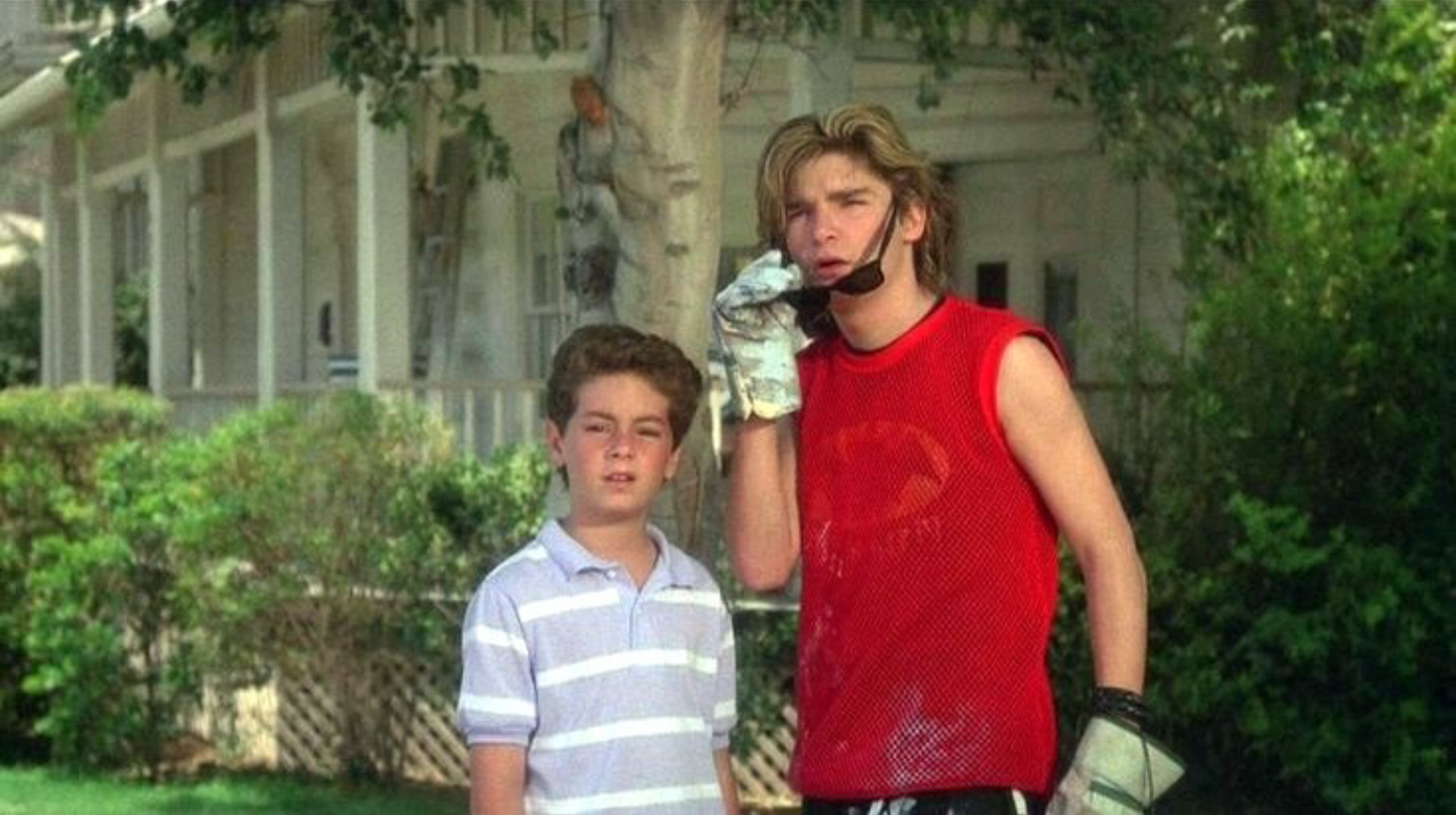

Next we have Ricky Butler (Cory Feldman) a stoner charged with painting his house while his parents are away. To Rick, life is a spectator sport and he has a front row seat to the events that will unfold in this idyllic cul-de-sac.

Gale Gorden (best known for playing Lucille Ball’s employer in the classic TV show, I Love Lucy) plays Walter, the old man with a perfect lawn whose eventual disappearance will act as the catalyst for the events that follow.

Finally there are the Klopeks (Henry Gibson, Brother Theodore and Courtney Gains) – the new neighbours from hell. They make strange noises late at night, they never speak to anyone and, possibly their worst crime of all, their lawn is a mess.

The ‘Burbs starts with questions which, in classic busy-body neighbour style, quickly become rumours and then outlandish accusations and recriminations. Who are the Klopeks? What happened to the previous owners, the Knapps? How come no one saw any removal vans when they moved out? Pretty soon, thanks mainly to Art’s overactive imagination, answers start to form: The Klopeks are serial killers or possibly devil worshipers, out for more blood.

To say that The ‘Burbs is a lot of fun is to understate the film to a colossal degree. It’s full of wonderfully colourful characters who are close enough to real to make them believable, yet far enough from reality to make them amusing, without ever falling into caricature. The three men at the heart of the film – Ray, Art and Rumsfeld – are children in adult bodies. They plough into the wildest mini adventures without thought of consequence, the streets and the gardens of Mayfield Place are their playgrounds and the military hardware that Rumsfeld owns and, reluctantly shares, are their toys.

This is not just subtext – the writer, Dana Olsen and director, Joe Dante, are well aware of this and play to it in some of the film’s funniest scenes. At one point Carol actually grounds Ray, and Art and Rumsfeld beg her to let him come out.

The women of The ‘Burbs are the adults – they are the ones who talk sense, who fight to keep their husbands on the straight and narrow, and who dispense both punishment and common sense when required. This is not to say that the film is being sexist and confining women to the role of mere bystanders for the sake of marginalising them. Yes, there is no doubt (like most Hollywood movies of the ‘80s) that the main focus of the film is the men, however, The ‘Burbs uses these tropes and stereotypes wonderfully. The women – represented by both Carol Peterson and Wendy Rumsfeld – are there to reflect the role of women, not in wider society, but in the household. They are the parents, the figures of authority that the ‘children’ need, they set boundaries and step in and act responsibly when required.

The most obvious example of this is when, frustrated by the various failed attempts to instigate contact with the Klopeks, the women round the men up, prepare brownies and put a welcoming committee together. This scene also provides us with the first opportunity to meet the neighbours. The Klopeks are made up of three generations of men. They live in a house that would double nicely as the Addams Family residence. It is notable that there is a distinct lack of the ‘female touch’ in their home. It is untidy, dusty and lacks any personal touches (apart from one very dubious painting). The frames on the sideboard still have the generic photos that they had when they were bought (cue Hans’ oft-quoted line, “It caaame with the fraaame”). The theme of the men as errant children and the women as responsible adults is continued here. If there was a woman in their lives, the Klopeks would probably look after the place, and themselves, better.

Of course, the more mysterious the Klopeks seem to be, the more determined the neighbours are to ‘out’ them and the more outrageous the humour becomes, culminating in the moment when they push too far and the only choice they have is to dig deeper (literally).

It could be argued that if there is one weakness with The ‘Burbs, then it’s the climax. For a film that focuses on and derives humour from the escalating antics of a group of neighbours, the ending may come as a bit of a cop out especially as the allegory – that the real freaks of suburbia lie behind the white picket fences and the wonderfully manicured lawns – is somewhat jettisoned in order to maintain Hanks’ good guy image. Yes, Art and Rumsfeld are the real freaks but ultimately their paranoia and childish imaginings are revealed to be correct. The alternative ending which can be found on the Blu-Ray and YouTube is in some ways more satisfying yet the ending we have has so much energy and excitement that any flaw is minimalised. One moment from the alternative cut I would have loved to see included in the final version has to be the Rumsfelds retreating into their house after all the excitement (Rumsfeld: “A bit of the old debriefing, pal”, before sweeping Bonnie off her feet and carrying her across the threshold!) as it is both amusing and also gives us a glimpse into the private life of this oddly matched couple.

Screenwriter Dana Olson based the cul-de-sac of Mayfield Place on experiences from his own childhood. He was struck by how a quiet neighbourhood in which very little seemed to happen could occasionally reveal a sordid underbelly of murderers and psychos. He approached The ‘Burbs, as ‘Ozzie and Harriet meets Charles Manson.’

Another obvious influence is the Hitchcock film Rear Window in which nosy neighbour, James Stewart, begins to suspect that one of his neighbours may have murdered his wife (you can read our in-depth essay on Rear Window here).

The script was sent to Imagine Films where producer Brian Grazer immediately thought it would be perfect for Joe Dante who, from a box office and media appreciation point of view, has always had an up and down career. In the few years before directing The ‘Burbs he had made the massively successful Gremlins (his third feature) followed by the crushing disappointment of Explorers and the mildly successful Innerspace. To fans of Dante, these films are all of a particular standard and their respective stories are told in a singular voice so that they have now become cult classics, but to the world at large they are either not taken very seriously or have been forgotten altogether. The ‘Burbs continued his off-center look at the American small town community. Like Gremlins and Explorers and both Matinee and Small Soldiers, The ‘Burbs looks beyond the white picket fences and the beautifully manicured lawns to highlight the absurd.

In many respects Dante resembles David Lynch in his pursuit of exposing this underlying darkness but whereas Lynch seems to want to peel away the facade because he has a certain disdain for it all, Dante seems to love it and wishes to celebrate it. It’s as if nostalgia is just as important as the darkness behind it. This is why The ‘Burbs works so well.

Nostalgia plays a big role in Dante’s films and often acts as the foundation upon which his movie will be built. Gremlins, for example, used Thorton Wilder’s Our Town and It’s a Wonderful Life on which to wreak havoc. Indeed, the town in Gremlins – Kingston Falls – sounds remarkably like the Bedford Falls of Frank Capra’s film. The ‘Burbs is one of the more contemporary of Dante’s films, although, like the technologically futuristic setting of Innerspace, it feels like it’s from another era, and this feeling is only emphasised now that the film is almost 30 years old.

There’s another admittedly tenuous link with It’s A Wonderful Life. By the time Hanks was cast as Ray Peterson, he was already building a reputation as a likeable and bankable star and very soon comparisons with everyone’s favourite everyman, James Stewart began to emerge. This comparison was used very effectively in The ‘Burbs cementing the link even further.

Hanks is at his very best here and it’s obvious that he had fun making the film and bought into the film’s philosophy. In the book, The Films of Tom Hanks (1996 – by Lee Pfeiffer and Michael Lewis) Hanks is quoted as saying “What’s so bizarrely interesting about this black psychocomedy is that the stuff that goes on in real life in a regular neighborhood will make your hair stand up on the back of your neck.” Early in the film Hanks plays Peterson fairly straight and conservative, often allowing Rick Ducommun and Bruce Dern to act as the children and get more of the laughs, yet he holds his own throughout and is never pushed aside by the other’s antics. Then, as Peterson slowly unravels, Hanks gets the opportunity to show some of his comedic chops; he does so with relish so that we have no other option than to be dragged along for the ride.

This slow descent into madness is perhaps best illustrated in what may be the most famous shot of the film. It is certainly the wackiest. Ray is already at his wits end and just wants to be left alone but Art keeps pushing. Then Ray’s dog digs up a bone, which according to Art is a human femur bone (“Where do you think this comes from? A Chicken?”). Art makes a logical leap and decides that it belongs to the missing neighbour Walter. The two men scream in terror and Dante’s camera quickly zooms in and out, again and again.

This smashes the fourth wall, reminding us that we are watching a film, yet, at the same time, it’s completely in keeping with the spirit of the movie and so doesn’t seem out of place at all. In interviews since, Dante has claimed that were he to make the film today, he would no longer use this particular shot, as if citing it an example of excess which should never have been allowed to happen. This shot absolutely belongs in the film. It’s a brilliant example of cinematic comedy, of a master in full control of his craft. It’s one of a number of shots throughout The ‘Burbs which may be considered jarring if they were in any other film, yet here it fits perfectly.

Take for example the scene at the breakfast table early in the film when Art and the Petersons are throwing theories back and forth as to who the Klopeks really are. It’s mostly filmed using a very standard approach, focusing on the ensemble with only the occasional cut but suddenly the angle changes the moment Ray’s son Dave says that he saw the Klopeks digging up their garden the night before. Suddenly we have a two shot – Art on one side, Dave on the other. It’s a shot that is in no way intended to be invisible, instead it’s there to highlight the absurdity of the moment with a comedic and filmic presentation as we are literally pulled in to the conversation at the moment where Art shares with Dave his dark suspicions.

Another example comes later when Art and Ray dare each other to knock on the Klopek’s door. As they start their approach the music rises – Ennio Morricone’s theme from My Name is Nobody. Dante tracks the two men as they get closer and closer, cutting away to zoom towards the faces of the watching neighbours, even focusing on Walter’s dog. Again, this is merely to highlight the hyperbolic absurdity of the whole situation and to do so Dante all but breaks the Fourth Wall once more. Suffice to say that these moments are what is so appealing to fans of The ‘Burbs.

There aren’t that many outright jokes in the script yet it’s consistently funny and wildly entertaining. The humour has its foundation in the simple fact that the characters are believable and likable, despite the preposterousness of the situation they create and their responses to it. It’s also a hugely quotable film with a lot of lines which might not be funny out of context but to fans are hilarious. Aside from the aforementioned scenes, The ‘Burbs is beautifully lensed by cinematographer Robert Stevens, each shot thoughtfully and precisely framed. This is evident from the very first shot which starts with the Universal Logo of Earth and slowly zooms in until the camera finds Mayfield Place. The ‘Burbs remains the only film to have the proper Universal logo appear at the end of the film.

The music too is sublime. Dante once again teamed up with the ever brilliant Jerry Goldsmith, who created a score that is quirky, uplifting and gleefully idiosyncratic.

It seems as if the cast and crew had a great time making the film and this is translated on to the screen. During filming Corey Feldman and Michael Jackson became friends and Jackson’s pet chimpanzee, Bubbles, often visited but was finally banned after it would relieve itself in the trailers where it was kept between takes and spread its poop over the trailer walls.

As you would expect from a Joe Dante film, there are a myriad of in-jokes and references to other films – the cereal in the Peterson’s kitchen has a picture of a Gremlin on it; there is a sledge in the Klopek’s house with the name ‘Rosebud’ on it; the TV shows images from The Exorcist, Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 and Ride With the Devil, and of course features cameos by Kevin McCarthy (cut from the final film), Robert Picado and Dick Miller – but this does not overwhelm the film. Instead they complement the ethos of the The ‘Burbs wonderfully.

The ‘Burbs is, to its many fans of which I am one, a true comedy classic. It is part of a quite remarkable run by its director starting with the flawed but still entertaining Piranha, then continuing with The Howling, Gremlins, Explorers, Innerspace, The ‘Burbs, Gremlins 2, Matinee and Small Soldiers. These films, along with some excellent work in TV, form a truly remarkable streak that very few directors would be able to match and you can’t help but wonder what Loony Tunes: Back In Action might have been like if the studio hadn’t interfered so much.

For me, The ‘Burbs and Matinee mark the pinnacle of this streak and The ‘Burbs in particular is a true cult classic. It’s a film that has a loving reverie of the often mundane absurdity of Americana and small town suburban life. It’s replete with some wonderfully quotable dialogue, some truly brilliant comedic performances from a perfectly chosen cast and is a film where every facet comes together to form a movie that has a small but strong and fiercely loyal following. The ‘Burbs is the ultimate feel good movie and by the film’s joyous ending you’ll be agreeing with Corey Feldman’s Rick with his final declaration, “God I love this street!”

Film ‘89 Verdict – 10/10

The ‘Burbs is available on Blu-Ray in the U.K. courtesy of Arrow Video and in the US courtesy of Shout Factory.