The History of ‘50s Science-Fiction Cinema – Part 2.

On July 29th 1953 The War Of The Worlds was released. Directed by Byron Haskin (Robinson Crusoe on Mars, The Naked Jungle) and produced by George Pal who had produced both Destination Moon and When Worlds Collide, The War of the Worlds is one of the most celebrated sci-fi films of the period. As with previous films discussed here, nuclear war and the science behind it play a prominent role in the film. It begins with an introduction by Sir Cedric Hardwicke outlining that the Earth had been chosen by the Martians because their cold and barren home planet was dying. Although this narrative is straight out of the original novel by HG Welles, it effectively mirrors the popular belief that, like the red planet, Russia was a barren cold country from which the people were desperate to escape.

The hero of the piece is Dr Clay Forrester (Gene Barry), a scientist who is working on the Manhattan Project, and is accompanied by Sylvia van Buren (Ann Robinson) who provides the obligatory love interest. Forrester witnesses a strange meteorite landing nearby so goes to investigate. He discovers a strange capsule which, hours later, opens to reveal an alien craft which promptly begins killing the locals with a ‘Heat Ray’. News soon spreads that there have been dozens of these devices landing around the world and now they are slowly advancing on the planet’s major cities in order to destroy them and wipe out the human race.

The War Of The Worlds began life as a novel which, on Halloween in 1938, was famously dramatised by Orson Welles on radio. This infamous broadcast led to mass panic throughout the US by people who, missing the show’s introduction which clearly stated that it was a Mercury Theatre Production, thought that they were in fact being attacked by enemies unknown. You have to remember that this was only one year before Europe erupted into war. It was on the radio news every night, in the newsreels, in the cinema and was constantly making headlines in the newspapers. It was in short, on everybody’s minds.

It’s an enduring story simply because it has so many applications to the world at large and, besides the 1953 film and the 1938 broadcast, there has also been a TV series in 1988 (with Ann Robinson reprising her role) as well as being remade as a big budget film by Steven Spielberg in 2005.

The film ends not with an earthling victory but with the Martians dying because of an inability to cope with the germs, bacteria and viruses that are prevalent on earth. As Sir Cedric informs us ‘Once they had breathed our air, germs which no longer affect us began to kill them. The end came swiftly. All over the world, their machines began to stop and fall. After all that men could do had failed, the Martians were destroyed and humanity was saved by the littlest things, which God, in His wisdom, had put upon this Earth…‘

Again, these last few lines are directly from Wells’ book, however they must have rung true to a God-fearing America who saw themselves as the main opposition to the atheistic Russians.

There is a reason why this production of The War of The Worlds has survived and flourished over the years. It is a beautifully made film with great cinematography by George Barnes. The screenplay by Barre Lyndon is spot on and there is a real sense of excitement and threat throughout as well as an epic scope and a feeling of a true global threat at play. It also won the Oscar for Special Visual Effects and in 2011 it was selected to be part of the National Film Registry in the U.S. Library of Congress.

Other notable films of 1953 include It Came From Outer Space (more on this one in a moment), Donovan’s Brain, a fun film although lacking in anything interesting to say, and the truly terrible Robot Monster (basically a gorilla body with a space helmet obscuring the face).

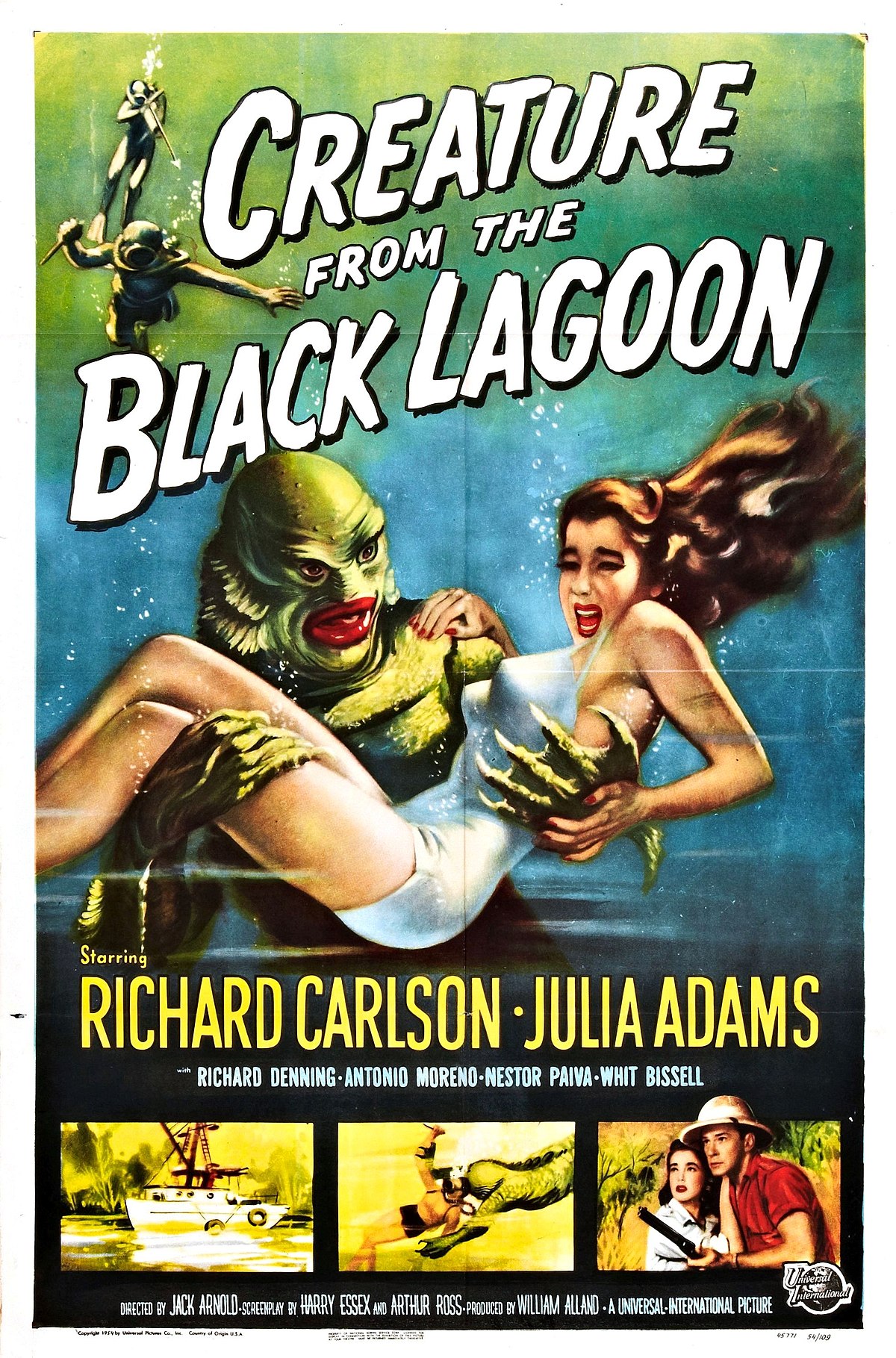

1954 was another bumper year for Science Fiction movies. The first great film of that year is one that has received a lot of press recently because of Guillermo Del Toro’s Oscar winning The Shape of Water – Jack Arnold’s masterpiece The Creature From The Black Lagoon.

Like George Pal, Jack Arnold is one of a few giants of this period of Sci-Fi. In 1953 he directed the fun but flimsy It Came from Outer Space (alien ship lands on earth, the local population start to act strange, distant and odd, very much like Invaders From Mars, only this time there’s a twist – the Aliens only want to repair their ship and leave Earth) and would go on to direct other films which we’ll cover later.

The Creature From the Black Lagoon is not about aliens from other worlds, or even the effects of atomic radiation on animal or plant life, it’s about an animal from the Devonian Age (416 million to 358 million years ago) which has somehow managed to survive in a remote part of the Amazon. In many respects, its closest cousin is possibly the 1933 classic, King Kong, but with a decidedly ‘50s sensibility. A team of scientists and adventurers travel into the Amazon on the ship Rita and are slowly picked off one by one by the mysterious Gill-man. Like Kong, the Gill-man seems to be attracted to the beauty of the piece, Kay Lawrence, played by Julie Adams. Queue some truly wonderful aquatic scenes, especially of Kay swimming at the surface of the river with the creature following and watching from her below.

The characters and their relationships are straight out of a good many science fiction films of this period but, like the other classics mentioned here, the quality of the writing, directing and special effects help the film to rise above any standard tropes it may bear.

The genesis of this story is particularly interesting. The film’s producer, William Alland, was told a story about a half-man/half-fish that was supposed to have lived in Mexico by cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa at, of all places, a dinner party during the making of Citizen Kane. Alland was acting at the time and he played the reporter Thompson who was given the task of tracking down the meaning of Kane’s last word “Rosebud.” Although his face is hardly seen in the film – it is always obscured by a distinct angle or a carefully placed shadow – it is an absolutely crucial role in what is regarded by many as the greatest monster film of all time.

Alland then wrote a short story entitled ‘The Sea Monster‘ which, like Kong, was based around the premise for Beauty and the Beast. The final film is a great adventure that has its fair share of excitement and tension. A definite must-see for all fans of this period.

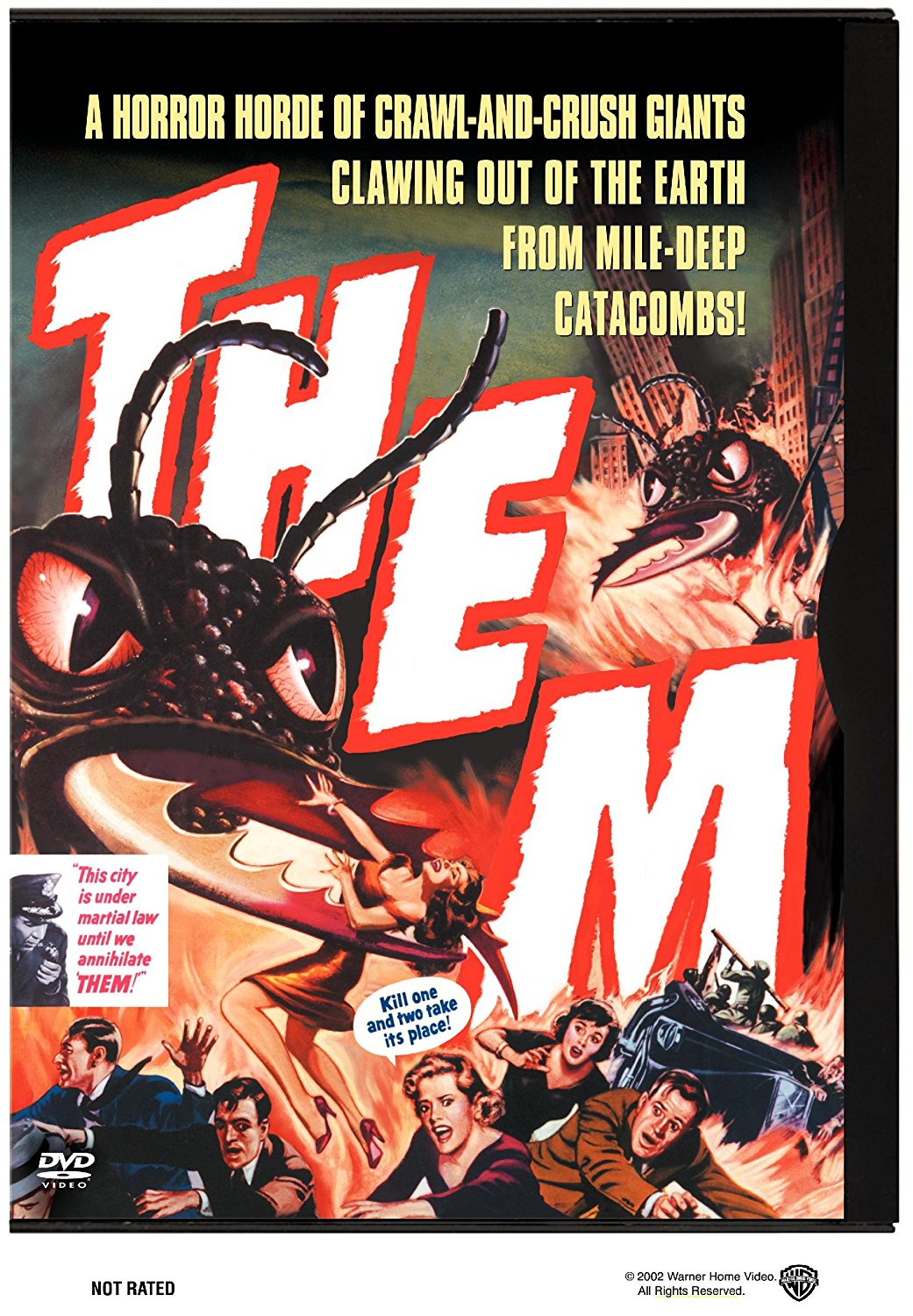

June 1954 saw the release of what might be my personal favourite science fiction film of the 1950s – Gordon Douglas’ Them! Returning to idea the atomic mutation, Them is based in Alamogordo, New Mexico, which was the location of the Trinity Test – the first Nuclear explosion on American soil. The story is simple; the radiation enters the soil and then into the food chain of the mighty ant. The ants then grow on a massive scale until they are towering over humans. What makes these creatures so effective is, firstly the marvelous special effects, and secondly, the iconic sound they make!

At the start of the film a young girl is found wondering the desert alone. She has been stricken mute from fear and stares out at nothing, not engaging in any conversation or answering any of the policemen’s questions. That is until she hears the sound, the high-pitched shriek of the ants. At this she comes alive, screaming loudly and shouting ‘Them! Them!’

We are joined on this journey into the desert once more by a scientist – Dr Harold Medford, played by Kris Kringle himself Edmund Gwenn, his beautiful daughter, played by Joan Weldon and the local police sergeant Ben Peterson, played by James Whitmore who, forty years later, would play Brooks Hatlen in The Shawshank Redemption. There’s also an early uncredited part for Leonard Nimoy.

What sets Them apart from many of the other films of the time is that it takes a serious, intelligent approach and doesn’t talk down to its audience. Many science fiction films of that period played it dumb but Them is actually a very smart movie. In the closing moments Gwenn speaks a line which perfectly sums up the fear that was confronting the world of the ‘50s;

“When Man entered the Atomic Age, he opened the door to a new world. What we may eventually find in that new world, nobody can predict.”

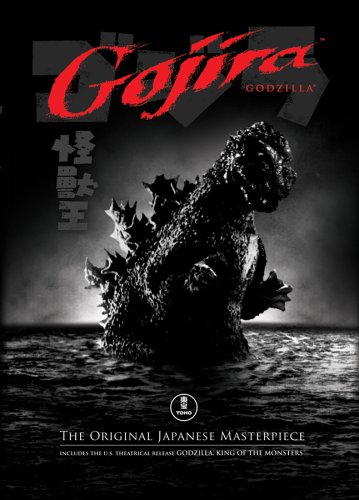

The third great science fiction film of 1954 is a bit of a departure. Even though the main focus of this piece is on American sci-fi, one of the most influential films of all time was released that year in Japan, Godzilla.

If anything, Godzilla illustrates how the fears of the US were replicated across the pacific. The big difference however, is that Japan had actually been the victims of a nuclear attack. Two of their cities had been destroyed and their whole culture and social systems had been changed forever.

The beast that rises from the sea was the embodiment of fear of a nuclear holocaust, it attacks indiscriminately and crushes everything in its path. The biggest difference between the US and Japanese approaches to these existential crises is seen in the main characters. As is the American way, the US films focused on individuals giving everything they’ve got to overcome the creatures, whereas in Godzilla, it is the bureaucracy – the social structures and governance – which are the focus. This approach is perhaps most evident in two recent remakes of Godzilla. The 2014 US version, directed by Gareth Edwards, focuses almost entirely on Aaron Taylor-Johnson’s military grunt Ford Brody, whereas in the 2017 Japanese remake, Shin Godzilla, directed by Hideaki Anno, the focus is exclusively on the government reaction to the crisis. (Our review of Shin Godzilla can be found here).

The first of many Godzilla sequels was released in 1955 and featured one of the worst titles of the series (a series which featured many dubious entries) – Godzilla Raids Again, which makes it sound more like a Mexican Western than a creature feature.

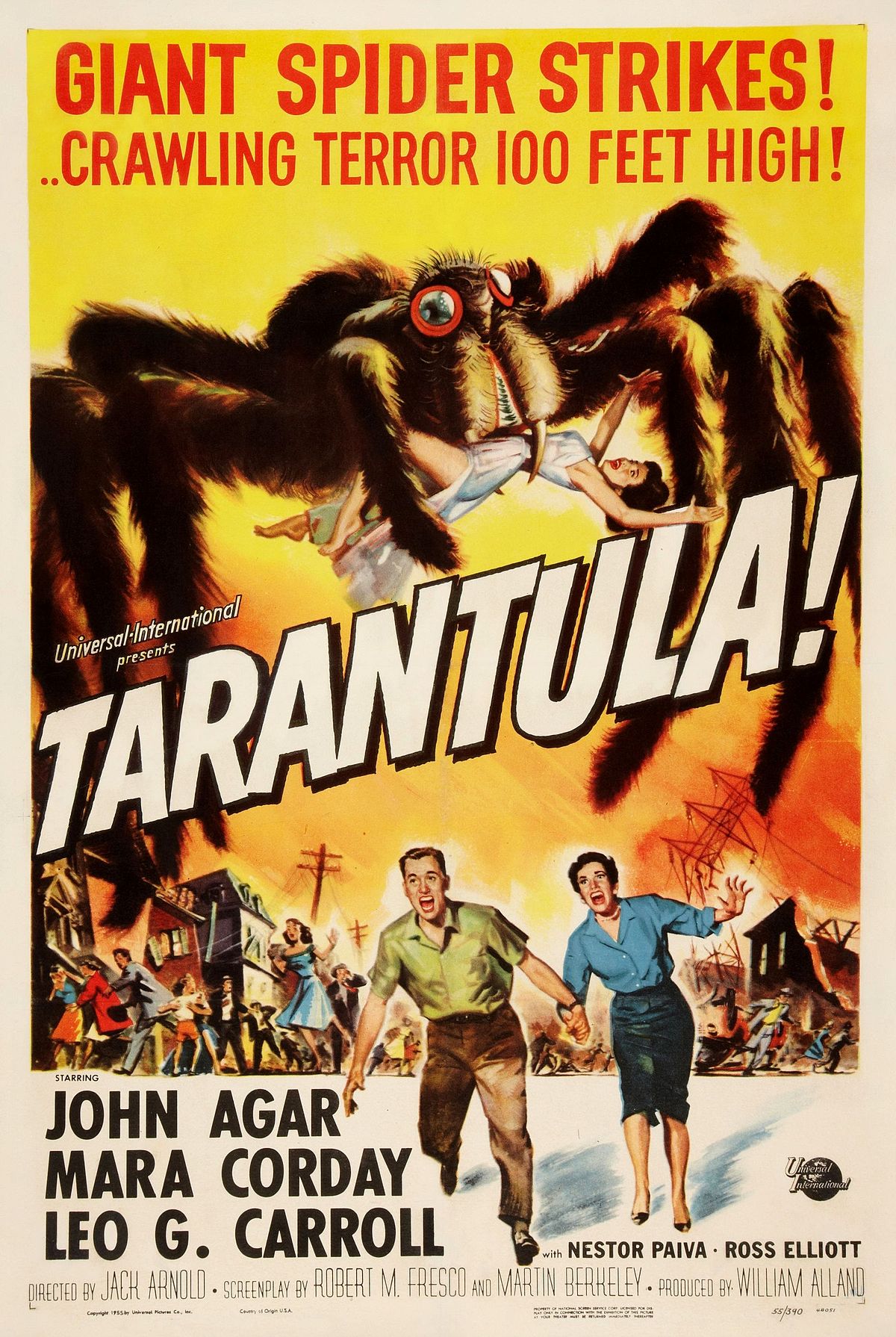

That same year in America, another great creature feature was released – Tarantula! Another classic directed by Jack Arnold, Tarantula tells a very familiar story – the consequences of when science goes bad. The titular creature here is a spider which has escaped from a laboratory where a doctor has been carrying out experiments aimed at increasing the size of animals. The spider grows rapidly until it starts eating full grown cattle. It has all the usual sci-fi elements, men in white coats pushing science too far, a beautiful young woman – Stephanie Clayton played by Mara Corday – a small slice of Americana under threat and the dashingly handsome hero Dr Matt Hastings (John Agar), and whilst there is very little in Tarantula that’s new or original, what is there works wonderfully. The special effects really are special, despite the obvious limits to the budget, and the threat seems real and immediate. The fear of spiders is one of the most common phobias and, projected to such a size, their unknowability is overwhelming.

Look out for a very brief glimpse of a young Clint Eastwood as a fighter pilot. He has a mask covering his face throughout yet, when he speaks, it’s unmistakably him. Tarantula was his second film – his first, released the same year, was the sequel to The Creature from the Black Lagoon – Revenge of the Creature. Also directed by Jack Arnold and starring John Agar, the sequel offers nothing like the quality of the first film.

Perhaps the most ambitious film of 1955 was the spectacular This Island Earth. Co-directed by Joseph M. Newman and, with his third film of the year, Jack Arnold.

The story involves another dashing scientist and jet fighter, Dr Carl Meacham (Rex Reason) who receives instructions to build a mysterious device called an Interocitor. He builds it and then discovers it was all part of a test which he passes. He is then taken to a secret lab run by a curious man called Exeter (Jeff Morrow). At the lab Meacham meets his old flame, Ruth Adams (Faith Domergue), who initially fails to recognise him. It transpires that Adams is pretending not to know him in case Exeter and his colleagues find out. Meacham and Adams escape, however, as they are flying away the small aircraft they are using is caught in a tractor beam and they’re pulled into a flying saucer. They are then transported to the planet Metaluna, Exeter’s home, which is under attack by the Zagons. Most of the story so far has been told with little flourish and is even a little flat, but once on Metaluna the film picks up considerably, if only for the truly amazing special effects and production design.

Jack Arnold was actually brought in after principal photography had been completed because the producers were unhappy with the original footage of Metaluna as shot by Newman. Arnold’s confidence and eye for dazzling effects is obvious. If you watch This Island Earth, don’t be put off by the opening scenes on earth. Make sure you stay to the second half, it’s certainly worth it.

A special mention has to be made for It Came From Beneath the Sea. Not the best science-fiction film of 1955, but worth a watch just to see the wonderful special effects which include a giant octopus attacking the Golden Gate Bridge. The octopus was designed and animated by legendary special effects master, Ray Harryhausen.

In the third and final part of this feature, we will cover the last years of this great decade, including such masterpieces as Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Forbidden Planet and The Incredible Shrinking Man.