The Searchers (1956).

John Ford once famously proclaimed ‘I make Westerns.’ Of course, this was an over-simplification of sorts. In a career that spanned 6 decades (his first film was in 1917, his last in 1976) he won 6 Best Director Oscars, none of which were for a western, yet this declaration still somehow defines him and his legacy.

And what a legacy. The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, Stagecoach, The Iron Horse and My Darling Clementine are but a few of his greatest. And these are just his westerns. He also made The Quiet Man, The Grapes of Wrath, Young Mr Lincoln, as well as two Oscar winning documentaries – The Battle of Midway & December 7th, each film being a masterpiece in their own right.

In addition to these undisputed classics, Ford also directed a western with one of the most complex characters in film history – Ethan Edwards in The Searchers. The story is deceptively simple yet full of nuance and understatement which requires multiple viewings to even scratch the surface of.

Ethan (John Wayne) returns to the home of his brother, Aaron, and sister-in-law, Martha, after many years away fighting for the Confederacy against the North. Although he witnessed the official surrender of the South, he himself has refused to surrender. Shortly after his arrival, they are visited by Captain Clayton (Ward Bond) and his deputies. A number of cattle have been slaughtered and Clayton is gathering deputies to investigate and to deal with the Comanche who are probably to blame. It soon transpires that the killing of the cattle was just a diversion to lure the men away so that the houses are unguarded.

Ethan (John Wayne) returns to the home of his brother, Aaron, and sister-in-law, Martha, after many years away fighting for the Confederacy against the North. Although he witnessed the official surrender of the South, he himself has refused to surrender. Shortly after his arrival, they are visited by Captain Clayton (Ward Bond) and his deputies. A number of cattle have been slaughtered and Clayton is gathering deputies to investigate and to deal with the Comanche who are probably to blame. It soon transpires that the killing of the cattle was just a diversion to lure the men away so that the houses are unguarded.

Ethan returns to Aaron’s house along with Martin (who Ethan refers to as a ‘half-breed because he is one eighth Cherokee), the adopted son of Aaron and his family, only to discover the house has been burned down, Aaron, Martha and their son, Ben are dead and the two daughters, Lucy and Debbie have been kidnapped.

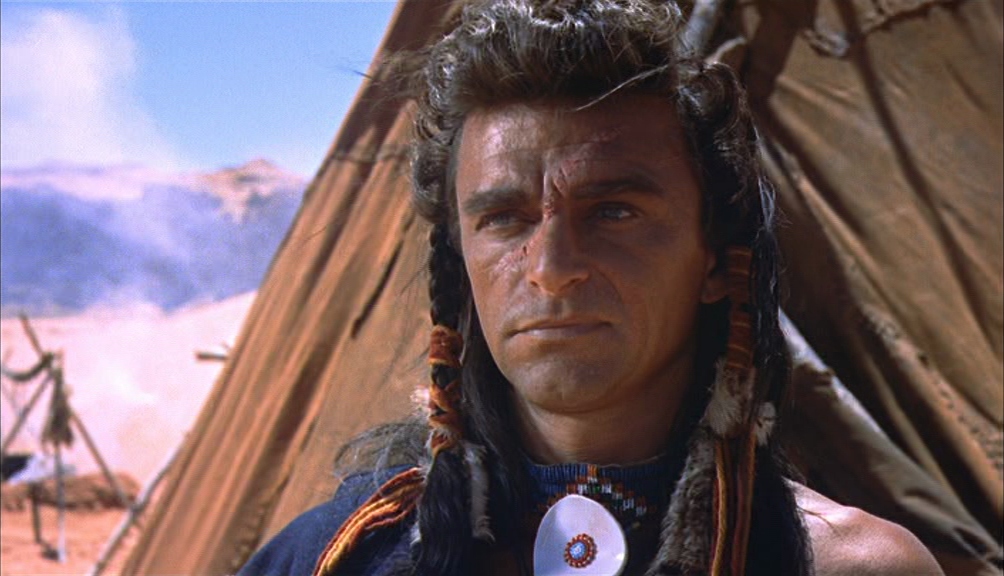

The rest of the film, as the title implies, involves Ethan, Martin and Lucy’s finance, Brad, searching for the two girls through the canyons of Monument Valley and down through Texas. It’s a search that will take them years, through desert heat to freezing snow, all the time hunting down a Comanche called Scar. But this is not what the film is about. The Searchers, despite its name, is not so much about the search and neither is about a group of people. It is, at its core, a study of one man – Ethan Edwards.

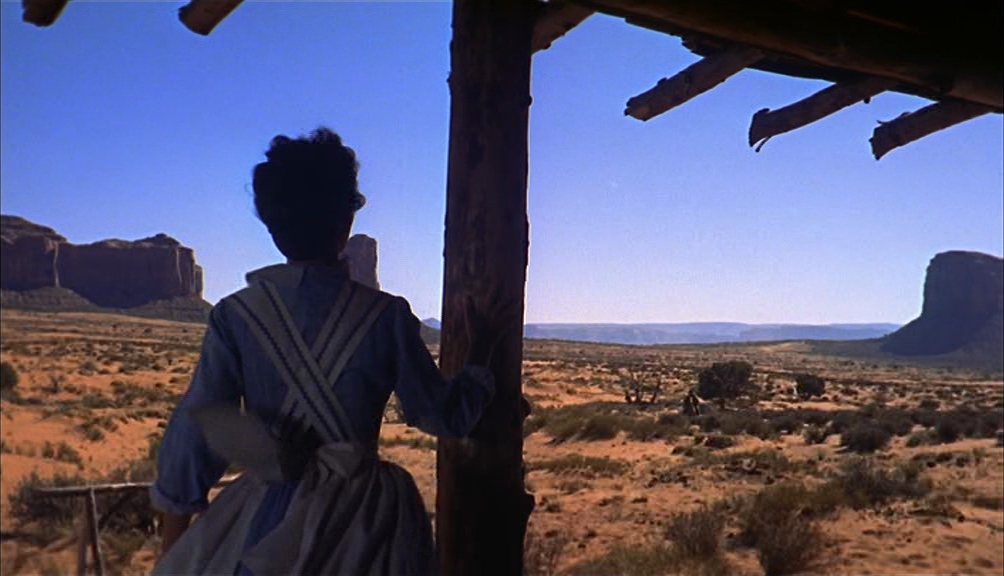

From the moment we first see him Ethan is a mystery. The opening shot, looking from inside the house as Martha opens the door and sees Ethan approaching on his horse, is like the opening of a book. We are introduced to Ethan through the eyes of others and this is something that will continue throughout. It is Ethan’s actions and the reaction of those around him that tells the story, but we are rarely told the whole story. Whereas normally in a Hollywood picture of this time the filmmakers would try to tie up every loose end, in The Searchers these loose ends are encouraged.

We first discover something about this enigmatic character through the children, as they excitedly ask him questions about his time away and his role in the civil war. We quickly realise that he holds no stock in the past and that there is the possibility that he could be wanted for a crime (he’s probably an outlaw for not surrendering to the Union army). His devotion to this lost cause reveals him to be stubbornly single-minded. He gives away his sword and his medal without much thought and he also has a bag of newly minted coins, although he refuses to explain where they come from.

There’s also a suspicion of a past love affair between Ethan and Martha. In one scene, as he prepares to ride out with Captain Clayton, Martha lovingly folds Ethan’s coat, smoothing it softly with her hands as if it’s of great value to her. Clayton sees her from the other room then turns his head, stoically refusing to see more than he already has. When Ethan comes into the room and kisses his sister-in-law on the forehead, Clayton remains, stubbornly not watching, staring into the middle distance. It’s as if he knows there is something there, something that’s been going on for some time, and he knows that he can’t interfere or acknowledge it. You can’t help but wonder what has happened between them in the past and if Aaron knows anything about it.

John Wayne was always known for playing the hero but, if anything, Ethan Edwards is more anti-hero. He is not a likable guy, despite his good-guy persona. This is a strength of Wayne which is rarely mentioned. He can play the flawed anti-hero wonderfully, just think of his performance in Howard Hawk’s Red River for example.

Here his character is troubling. He is certainly a racist, not just in a casual sense as many were at the time, but in a very aggressive and angry way. Early on in the film the posse discover the remains of a Comanche buried under a rock and Ethan can’t help but shoot the dead man in his eyes, condemning his spirit “to wander forever between the winds” and not be able to enter the spirit lands. His hatred for the native Americans lives beyond this life and into the next.

Yet he has little time for Christian preaching, even cutting his brother’s funeral short because “there’s not even time for praying, Amen.”

This is not to say that he is a hard, soulless man without feelings. Ethan refuses to let Martin see Aaron, Martha and Ben’s bodies to spare the younger man the tragedy and later, when they find Lucy’s body, he initially refuses to acknowledge what he has seen. Later, when the truth comes out it is obvious that these instances have scarred him, and added fuel to his anger.

But at this moment, when true humanity momentarily peeks through his tough-guy persona, he willingly allows Brad, pushed to the limits of grief on hearing his lover’s fate, to charge into the Comanche camp and face an inevitable death.

The relationship between Ethan and Martin provides the meat of the film but only as a way of revealing more about Ethan’s obsessiveness and disregard for others and although it seems that the two men get closer as the years go by, you never really trust him. In fact, I would go as far as to say that they don’t as much get closer, they just get accustomed to each other.

It soon becomes apparent that Ethan doesn’t want to rescue Debbie but wants to kill her. She has been tainted by the Indians who have adopted her and his hatred and prejudice determines that she is no longer human, she is a savage.

Throughout The Searchers there is a subplot involving Martin’s fiancé Laurie and her exasperation with Martin’s inability to settle down with her. This is perhaps the weakest part of the film but it does illustrate exactly what the young man is giving up as he joins Ethan on this quest.

So why did Wayne and Pappy (the name the cast and crew used to refer to Ford as) create such a scornful and despicable character? You get a sense that there was a change in Ford in that he was reaching for something. Westerns were often laced with an identifiable undercurrent of racism. The whole dismissal of the plight of the native Americans and their depiction as savages to be feared, was always deeply troubling and it seems that Ford was aware of this. Only 8 years after The Searchers he directed the revisionist western Cheyenne Autumn, which tried to show a different side to the Indians. The Searchers was Ford’s attempt at highlighting the obsessive hatred and anger that lies behind racism. Whether he achieved this is debatable especially as the Comanche are fairly one dimensional in heir depiction and Ethan’s last minute conversion could be seen as him realising that Debbie is still white and thus deserving of being saved.

But if viewed as a character study andmif we accept they nobility of the intention – especially at a time when such nobility was very rare – then The Searchers is undeniably a masterpiece. It’s certainly one of the most influential Westerns of all time with references to it in Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets and George Lucas’s Star Wars (the scene when Luke returns home to find his house burning and his aunt and uncle murdered is an obvious reference) and its influence can be clearly seen in Wim Wender’s Paris, Texas, Paul Shrader’s Hardcore and Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (which Schrader also wrote). Ethan’s oft-repeated line “That’ll be the day” also became a Buddy Holly song.

As you’d expect with a John Ford film, the vistas of The Searchers, filmed in his beloved Monument Valley, are stunning. Winton C. Hoch’s photography is exceptional and the music by the ever brilliant Max Steiner is as to be expected.

The final shot of the film is the very definition of iconic. Having delivered Debbie back to civilisation, the camera mirrors the opening shot of the film. Looking out through the door, each character enters, happy that the search is over and that life can now settle down. All that is, except Ethan, whose gaze follows the others inside only for him to turn and walk away to the tune of Stan Jones singing the theme tune, Ride Away. In this scene, Wayne holds his right hand with his left, mimicking his great friend and mentor Harry Carey, whose widow was watching them film the scene from behind the camera. It is a poignant moment and we wonder where this man could possibly go now. What we do know is, as the door closes on him, he is not destined to live a quiet, settled life.

The lyrics of Stan Jones’ song asks “What makes a man to wander?” We might not get an answer to this question, but we are given a glimpse into the soul of a wondering, troubled man. The film offers no firm resolution as to whether Ethan is redeemed in terms of his fierce prejudice and whilst no comfort is given in that regard, the film is all the braver for not taking the conventional path of redeeming a flawed protagonist. Unfortunately for Ethan, his prejudice is a core aspect of his character. He may well change over time but as is often the case in reality, sometimes human flaws and foibles aren’t conveniently washed away for the purposes of a happy, or at least in this case a comforting ending. Whilst he leaves this aspect of Ethan’s character ambiguous and denies us firm answers as to where Ethan will go from here both literally and figuratively, what Ford has most certainly given us is one of the very greatest westerns ever made and a film that is worthy of the term masterpiece.

Film ‘89 Verdict – 10/10