Hong Kong and China – 21st Century Martial Arts.

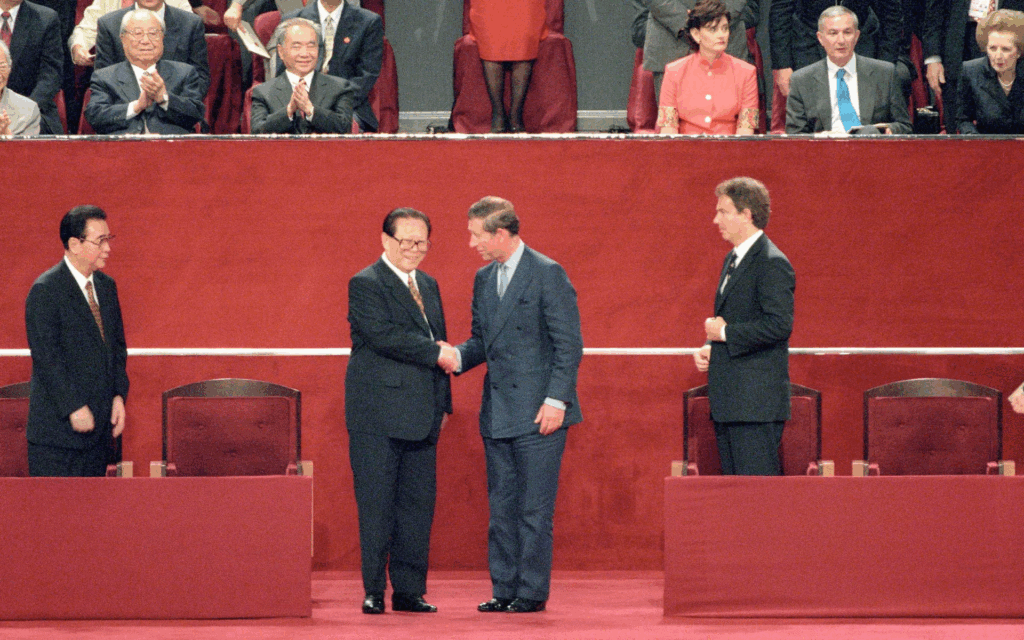

On July 1, 1997, Hong Kong, a British colony since 1842, once again became part of China. Although it had been agreed that Hong Kong Island, the Kowloon Peninsula, and the New Territories would retain a certain level of independence, the transition was undeniably significant. For many, it represented the end of an era, while for others it was a moment of new beginnings. Beyond the political ramifications, this shift marked a turning point for the cultural landscape of both Hong Kong and China. A city that had thrived as a global hub of commerce and creativity now found itself re-negotiating its identity. Hong Kong cinema, which had been a dynamic and innovative force for decades, would soon play an essential role in bridging Eastern and Western sensibilities, shaping the global perception of Chinese storytelling and martial arts culture.

China itself was changing. While the country remained autocratic and authoritarian, it was simultaneously opening itself to foreign influence in unprecedented ways. The Chinese government recognized the potential of cultural exchange, particularly through cinema. Hollywood, ever alert to lucrative markets, saw in China the second-largest audience in the world. Yet the relationship was not simply transactional. The Chinese approach to film was strategic, a blend of cultural preservation, soft power, and market experimentation. Initially, foreign films were allowed only in a restricted number, each carefully monitored and censored to ensure alignment with Chinese values. Over time, the Chinese film industry would absorb lessons from American distribution, marketing, and storytelling, gradually creating a domestic industry capable of producing films that were both commercially viable and culturally resonant.

Hong Kong films had already begun entering the Chinese market in the 1980s. Stars like Bruce Lee became symbols of cultural pride and resistance. In Fist of Fury (1972), when Lee smashed the sign reading ‘No Dogs or Chinese,’ audiences felt a deep appreciation with his defiance. More than a decade after his death, his influence continued to inspire Chinese audiences, as well as international viewers. The success of Hong Kong martial arts cinema rested on its ability to balance complexity and accessibility. While the historical and cultural contexts of the films were deeply Chinese, their narrative simplicity – the moral dichotomy of good versus evil, the struggle between rich and poor, the triumph of the honourable over the dishonourable – made them universally relatable. This is why Jackie Chan, Michelle Yeoh, Jet Li, Donnie Yen, and Chow Yun-Fat became household names long before many Chinese audiences had experienced their work. Hong Kong cinema’s global appeal lay in this precise balance, rich, cultural specificity combined with universally recognisable human themes.

The 1980s and 1990s marked the internationalization of Hong Kong cinema. Films that had been cult hits in the West gradually became mainstream. Jackie Chan’s early work in Hollywood, beginning with The Cannonball Run (1981), signalled the start of a broader trend, Hong Kong stars integrating into Western markets, bringing martial arts, acrobatics, and a distinctive sense of cinematic humour to new audiences. Yet these films were never mere spectacles, they were cultural artefacts, conveying moral lessons, national pride and the philosophical underpinnings of martial arts traditions.

Ang Lee, born in Taiwan in 1954, represents another dimension of this evolution. His feature debut, Pushing Hands (1991), introduced international audiences to his unique blend of art-house sensibility and accessible storytelling. The subsequent films in his ‘Father Knows Best’ trilogy, The Wedding Banquet (1993) and Eat Drink Man Woman (1994), reinforced Lee’s reputation for bridging Eastern and Western perspectives. He skillfully navigated cultural nuances while crafting narratives that resonated globally. When his former collaborator, Hsu Li-kong invited him to direct a wuxia film, Lee embraced the opportunity, resulting in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000). The film epitomized the international appeal of Chinese martial arts cinema, blending intricate swordplay, deeply human narratives, and breathtaking visual artistry.

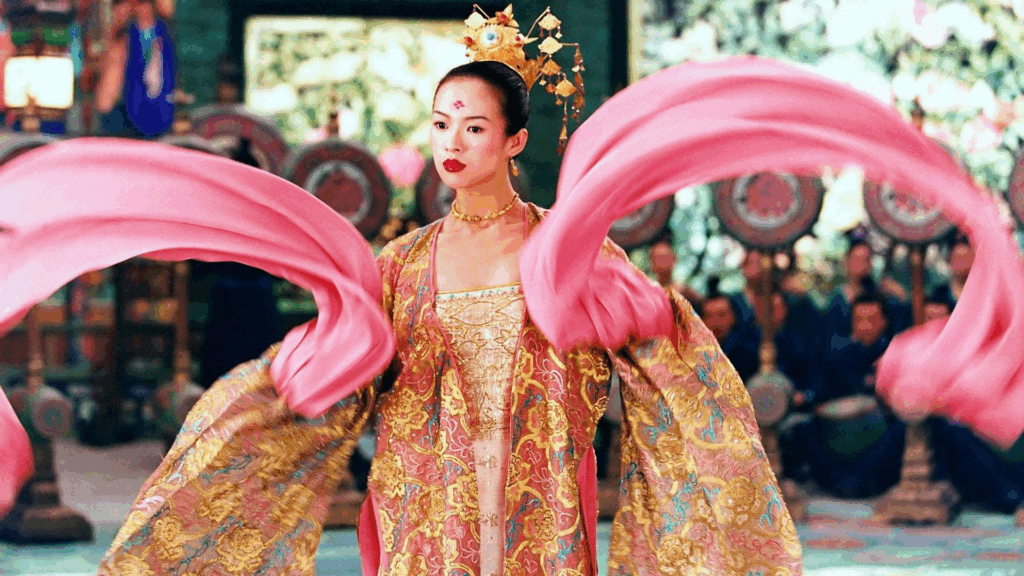

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon tells the story of Li Mu Bai, a renowned swordsman whose legendary skills and moral code are tested when the treasured Green Destiny sword is stolen. Alongside him is Yu Shu Lien, a woman of extraordinary combat ability and unfulfilled romantic longing. Zhang Ziyi’s character, Jen Yu, adds a complex layer of youthful rebellion, romantic desire, and martial ambition. The narrative weaves together multiple storylines yet remains accessible, demonstrating the hallmark balance of wuxia cinema; specificity in character and culture, universality in human emotion. The film’s success was unprecedented, grossing $213.5 million worldwide and becoming the first foreign-language film to earn over $100 million in the U.S. market. It received ten Academy Award nominations, winning four, a testament to its global impact.

What sets films like Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon apart is their meticulous choreography and visual storytelling. Fights are not mere displays of violence but highly stylized dances, where swordplay and acrobatics merge with narrative and emotion. A particularly striking sequence involves a duel between two warriors in the rain. The fight, presented partially in slow motion and imagined through the characters’ perspectives, emphasizes anticipation, respect and inner focus. Every movement is purposeful, every frame a potential work of art. It is in sequences like these that martial arts cinema transcends mere action, evolving into a form of visual poetry. Roger Ebert’s praise of Hero, Zhang Yimou’s 2002 epic, highlights this; “It demonstrates how the martial arts genre transcends action and violence and moves into poetry, ballet, and philosophy.”

Hero tells the story of Nameless, an assassin seeking to approach the King of Qin, intertwined with the recounting of three previous assassinations. The film’s use of color, narrative structure, and philosophical undercurrents exemplifies the sophistication of modern wuxia cinema. Each story is presented in a unique visual palette, reinforcing mood, perspective, and moral ambiguity. Fights are carefully choreographed to reflect character, intent, and emotion, rather than mere spectacle. These films, alongside House of Flying Daggers and The Grandmaster, collectively demonstrate the evolution of martial arts cinema from niche entertainment to international art form. The balletic movements, wire-work stunts, and integration of narrative and emotion distinguish them from standard Western action films, presenting an alternative cinematic language.

This internationalization of Chinese martial arts cinema coincided with strategic cultural initiatives by the Chinese government. The state recognized the dual potential of cinema as both a form of soft power and a domestic industry. Films like Ip Man (2008), starring Donnie Yen, not only provided compelling narratives but also reinforced national identity and cultural pride. The film recounts the life of Ip Man, an honorable and skilled martial artist who navigates personal loss, occupation, and national humiliation, ultimately demonstrating resilience and moral integrity. The blending of biography, action, and subtle nationalist messaging exemplifies China’s approach to cinema; instructive yet entertaining, culturally resonant yet globally accessible.

By the 2000s, Hollywood and China increasingly collaborated. Co-productions allowed studios to access Chinese locations, talent, and market audiences, while Chinese filmmakers gained expertise in large-scale production and international marketing. Rush Hour 2 (2001), starring Jackie Chan, exemplifies this trend; set in Hong Kong, yet crafted to appeal to global audiences, blending humour, action, and cross-cultural storytelling. The dynamics between the two film industries illustrate a broader tension; globalisation versus cultural sovereignty. Hollywood sought profit, China sought both cultural preservation and the development of a competitive domestic industry. Over time, this collaboration shaped cinematic tastes, influenced narratives, and contributed to the growing sophistication of Chinese film production.

Beyond commercial considerations, martial arts films serve as vehicles for philosophical, cultural, and ethical discourse. Themes such as honor, loyalty, sacrifice, and the tension between individual desire and societal duty recur throughout the genre. In Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Jen Yu’s conflict embodies this tension; she must reconcile personal longing with her obligations to family and society. Similarly, in House of Flying Daggers, the interplay between love, loyalty, and deception highlights the moral complexities inherent in human relationships. Martial arts cinema therefore operates on multiple levels; visual spectacle, narrative engagement, cultural reflection, and philosophical exploration.

The aesthetic sophistication of these films also extends to their cinematography and production design. Zhang Yimou’s House of Flying Daggers utilizes vibrant colors, intricate set design, and natural landscapes to enhance narrative meaning. The Peony Pavilion sequence, in which Jin and Mei engage in the Echo Game, demonstrates the interplay of choreography, color, and tension. The action sequences are visually stunning, but they also convey character and emotion, blending physical movement with narrative purpose. The Grandmaster, directed by Wong Kar-wai, further illustrates the artistic potential of martial arts cinema. Its focus on shadow, light and slow motion transforms combat into a poetic and deeply personal expression, where every gesture carries emotional and narrative weight.

The commercial success of these films underscores their universal appeal. While Hollywood blockbusters like Avengers: Endgame rely on spectacle, the martial arts films’ global reach stems from their integration of culture, philosophy, and emotion. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Hero, House of Flying Daggers, and The Grandmaster collectively demonstrate that martial arts cinema is not merely action-driven but a comprehensive art form that resonates with audiences across cultures. These films are not only visually captivating but intellectually and emotionally stimulating, reflecting the depth and sophistication of Chinese storytelling traditions.

China’s strategic use of film extends beyond aesthetics and entertainment. Domestic policies have encouraged local production, increased cinema attendance, and promoted national narratives. Films like The Battle at Lake Changjin (2021), directed by Chen Kaige and Tsui Hark, reflect this dual approach; commercially viable yet ideologically aligned. By controlling narratives and supporting domestic production, China has cultivated a robust film industry that competes internationally while promoting national culture. Co-productions with Hollywood have served as both educational experiences and market entry strategies, allowing Chinese filmmakers to adopt global best practices while preserving cultural authenticity.

The evolution of martial arts cinema thus represents a broader interplay between tradition, globalisation, and technological innovation. From Bruce Lee’s defiant early films to Ang Lee’s sophisticated wuxia epics, the genre has traversed cultural boundaries, captivated global audiences, and influenced cinematic techniques worldwide. The choreography, visual composition, and narrative sophistication of these films have raised action cinema to an art form, demonstrating the enduring cultural power of martial arts and Chinese storytelling.

As China’s film industry continues to grow, its influence on global cinema is likely to expand further. The challenge lies in balancing commercial viability, ideological considerations, and artistic expression. Yet, the history of martial arts films illustrates the capacity of cinema to serve as a bridge between cultures, a repository of tradition, and a medium of universal storytelling. The future promises continued innovation, collaboration, and exploration, ensuring that martial arts cinema remains a vibrant and influential force in global film culture.

Success in filmmaking is often a marriage between art and commerce. In China, politics and culture are also significantly important. It is a three-way dance in which filmmakers must succeed. In the age of streaming, this is even more important. The recent film, New Kung Fu Cult Master 1, directed by Wong Jing (who spent part of his career as a writer for the Shaw Brothers) is a perfect example. A Chinese/Hong Kong production, released on streaming services, and starring Donnie Yen. The past and the future together.

In conclusion, the history of martial arts films in Hong Kong and China is a story of artistic ingenuity, cultural exchange, and strategic adaptation. These films blend narrative simplicity with cultural specificity, aesthetic beauty with philosophical depth, and local relevance with international appeal. They have reshaped global perceptions of Chinese culture, influenced Hollywood storytelling, and created a lasting legacy that bridges continents and generations. From Bruce Lee to Jackie Chan, from Ang Lee to Zhang Yimou and Wong Kar-wai, martial arts cinema has transformed both film and cultural history, illustrating that the language of action can be a universal medium of art, philosophy, and human connection. As the Chinese film industry continues to evolve, it carries forward a tradition that is both deeply rooted and globally resonant, ensuring that the legacy of martial arts cinema endures for generations to come.