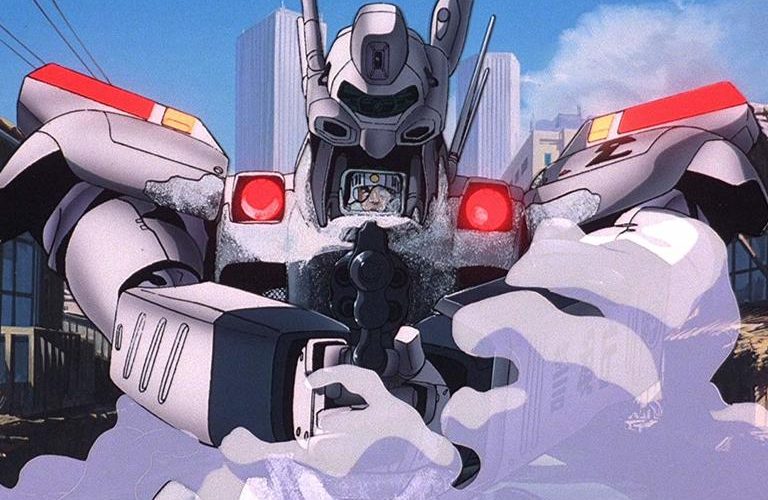

Patlabor: The Movie (1989).

Mamoru Oshii has produced genre work that continues to be analysed and discussed to this day, with a level of nuance and ambiguity that’s less narrative and more intellectual. His is a type of stimulant that satisfies our need for infinitely relevant and revealing storytelling.

Oshii’s first major animated feature work does not exist in the same company as Ghost in the Shell, and how could it? Patlabor: The Movie spins off of a series on which Oshii was already heavily involved, and follows a reserve team, part of a division in the Tokyo Police Force tasked with responding to Labor-related crimes. Labors are towering, mechanical units controlled by workers to carry out jobs with an efficiency never rivalled before in human history. This groundbreaking technology leads to the beginning of development on the Babylon Project, a land reclamation process whereby the bay surrounding Tokyo will be converted into liveable land to combat rising sea levels in the coming century.

At the centre of the project is The Ark, an island structure that acts as the heart of the project and houses all of the Labors. The film marks the beginning of a long creative partnership between Oshii, writer Kazunori Ito (already involved in the television series at the time), and composer Kenji Kawai, adding a certain uniformity to Oshii’s body of work. Religious symbolism is etched into the foundations of Patlabor; Oshii is pointing the finger at humanity’s god complex. This isn’t to suggest that the film is a study on the same level as Oshii’s later films; it’s not. It’s a far more direct narrative, to such an extent that its religious motifs act more as winks and nods and don’t necessarily demand a more active reading. The plot revolves around the discovery of a flaw in the newly implemented Operating System that’s being installed into the Labors, called HOS (Hyper Operating System).

This discovery however, opens up a larger mystery pertaining to the designer of the new Operating System itself, whom we see fling himself from the rooftop of the Ark at the very beginning of the film. Eiichi Hoba is its most interesting figure. It’s a shame then that his character is defined as little more than a psychopath who becomes obsessed with the religious connotations of the Babylon Project and acts out his own will on it. He creates a self-replicating flaw in the system that causes the Labors to act out and go berserk. Hoba, for his genius, earns himself the nickname “Jehovah” by his peers. This is Oshii and Ito at their most undisguised.

Hoba as an anarchist who reacts to human attempts at playing God is a fascinating concept, and ironically it’s his own hubris that leads to him killing himself before, such is his confidence, even learning that his scheme would succeed. This aspect of the narrative lingers in the background to make way for a humanistic story with a focus on relationships and camaraderie, spread between three stunning action sequences. All of this makes for as accessible a film as Oshii has ever produced. Despite being a continuation of a television series, the film stands alone quite competently. Opening with a feverish fight against a rogue Labor, the film quickly deviates into an explosion of exposition to bring us up to speed on the state of things. We meet leads Asuma Shinohara and Noa Izumi, and later the rest of Division II’s members. Asuma’s own father runs Shinohara Industries, a Labor manufacturer at the centre of the recent spate of Labor flaws. Noa becomes concerned when she learns of the dangerous new Operating System and its potential to affect her own Labor.

Both Asuma’s familial connection and Noa’s concern for her Labor are opportunities to wedge emotional stakes into the narrative. The script though has little time to acknowledge the weight these scenarios might otherwise carry. Though it surpasses the formulaic nature of feature film spin-offs from serialised anime by way of its gorgeous aesthetic and quasi-consequential storyline, it certainly seems to reinstate the status quo rather too cleanly. A chance to offer payoff to Noa’s internal story arc appears at the very end, when she must sacrifice her own Labor in order to rescue a trapped colleague. The film ends so abruptly after this altercation, and with so little regard for the resulting destruction, that it quite clearly bears no significance going forward.

Patlabor, much like Oshii’s future works, refers to the advancement of technology as neither having a good nor bad affect on everyday life; instead, it just is. There is no debate over whether Labors are a danger to society or a benefit, but rather that they are both. When two middle-aged engineers discuss the speed at which the world has changed, they neither bemoan nor do they celebrate their growing insignificance. Characters frequently address this reliance as essential but irrelevant without human talent behind them. In the world of Patlabor, one seems unable to exist without the other (sound familiar?) That said, much of what we see of Tokyo is destitute, and an argument can be made for Hoba’s motives being connected to the deplorable living conditions of the city’s lower class. So despite the effectiveness of modern technology, it cannot solve (and may even be a part of) the growing poverty.

There’s some politics involved as the film heads toward its climax – itself a rather compelling infiltration of the Ark amidst the looming threat of a typhoon. Asuma and Noa’s team must act outside of the law when the manufacturer and even the authorities refuse to, more concerned with maintaining good consumer relations than averting disaster. This again is a frequent theme among Oshii’s work. There’s a distaste for authority that’s directly and intentionally at odds with the emphasis on militant action. Contrast the explosive show of force deployed at the beginning of the film and the slums through which two Labors later do battle with little regard for the people below and the point is clear.

For all of the subtext that can be extracted from this prototype of the Oshii we would see in later films, Patlabor: The Movie is first and foremost focused on entertaining fans and bringing fresh eyes to the franchise. Moments of exhilarating action do not overshadow a story that otherwise has both feet planted on the ground. While there’s no tangible antagonist for the heroes of the film to go up against, Oshii’s greatest strength might be that he mitigates the need for one. If nothing else, the conflict is always clear. And if Patlabor is considered a lesser Oshii film, then his status is well earned.

Film ’89 Verdict – 7/10