The First Golden Age of Martial Arts Cinema, 1970 – 1980.

The history of cinema is filled with eras, movements, and waves, many of which we regularly celebrate. However, one pivotal era has not always been taken seriously. Unlike obvious cinematic movements like the Nouvelle Vague or the post war Neo-Realist films of Italy which were made by serious filmmakers attempting to redefine the language of cinema, Martial Arts movies have been almost entirely made for entertainment purposes. Made in the former British Colony of Hong Kong, they were made to be enjoyed by as wide an audience as possible, whilst also being somewhat esoteric, focusing entirely on the local culture, a culture far removed from that understood by Western audiences.

Yet, in the 1970s, Hong Kong martial arts cinema experienced a revolutionary transformation both within Hong Kong and on the international stage. During this period, filmmakers like Bruce Lee, Jackie Chan, and directors such as King Hu and Chang Cheh redefined the martial arts film landscape, elevating it to a global phenomenon; one that transcended culture and, through the grace of its dance like action sequences and its sometimes-simplistic stories featuring good guys and bad guys, became a global phenomenon that changed action cinema throughout the world. If it weren’t for Hong Kong Kung Fu movies, we would have no John Wick, no films such as the global Indian hit RRR, or Indonesian films such as The Raid. Hand to hand combat in old Hollywood movies was often little more than a brawl. Kung Fu movies made them into an art form, highly choreographed and elaborate. Even big budget movies such as the Marvel Cinematic Universe films would be drastically different without the influence of these low budget Hong Kong movies made fifty years ago.

China was still experiencing the impacts of the Cultural Revolution (officially ended in 1969 but continued until Mao’s death in 1976), and films from Hong Kong were banned. However Martial arts, deeply rooted in Chinese history and philosophy, with its rich tradition, easy accessibility and entertainment value, were evidently an obvious means of expression for the people of the island. Film studios such as The Shaw Brothers Studio, and its rival Golden Harvest, played crucial roles in shaping the martial arts film genre. Their focus on elaborate sets, intricate choreography, and stylized storytelling set a benchmark for the genre’s aesthetic.

The birth of the movement started with the 1938–39 two-part movie, The Adventures of Fong Sai-yuk, about the adventures of the folk hero of the same name (a semi fictional character that was to feature in many films, most notably Jet Li’s The Legend (1993)). But it wasn’t until almost 30 years later that the genre really took off, with films such as Dragon Inn (1967), Come Drink With Me (1966, both directed by King Hu), and The One Armed Swordsman (1967) directed by Chang Cheh. By the turn of the decade, the stage was set for a cinematic revolution that would bring martial arts movies to the forefront of international cinema. To cross that bridge from a local expression of identity to a global phenomenon, a catalyst was needed, and for that, Hong Kong Cinema would rely on one of its American diaspora.

Without doubt, no discussion of Hong Kong martial arts cinema in the 1970s is complete without acknowledging the unparalleled impact of Bruce Lee. Lee, an iconic martial artist and actor, revolutionized the genre with his charisma, skill, and visionary approach to filmmaking. Born in San Francisco and raised in Hong Kong, before returning to the US to start his career, Lee was an actor who could easily be embraced by both the east and the west, and his entry onto the global stage changed the image of martial arts films and popularized the genre worldwide.

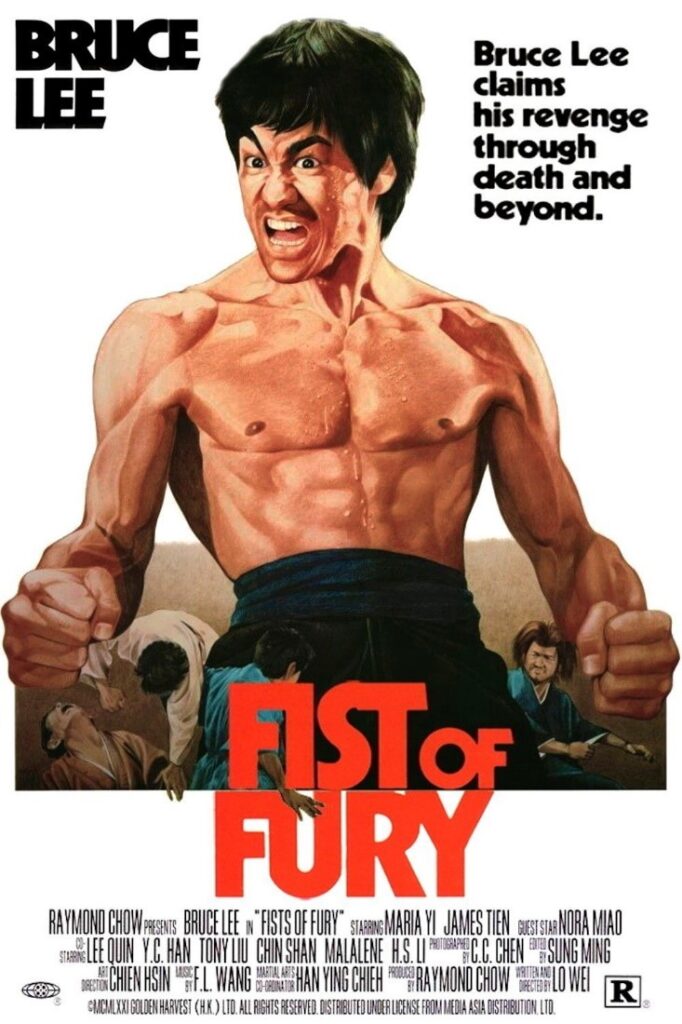

He was an actor the Hong Kong people could be proud of. Someone in whom they could see all they wanted to be. In 1949 Chairman Mao famously declared that the Chinese People had ‘Stood Up!’. This statement of pride to the people of China – and by extension Hong Kong and Taiwan – and defiance to the rest of the world, is reflected in the moment when Lee smashes a wooden sign declaring ‘No Dogs and Chinese Allowed’ in Fist Of Fury (1972 – directed by Lo Wei). In Bruce Lee, the people of China saw an individual embracing their culture and shared in his international success and reputation. His story would have been especially inspiring when you consider that Lee had first tried to make it big in Hollywood and, aside from a supporting role in the TV series The Green Hornet, had been mostly rejected by the West. It’s ironic that it was only on his return to Hong Kong was he able to conquer the world.

Lee only returned to Hong Kong at the urging of actor James Coburn, who pointed out that the province was growing in prominence and in output. On arrival, Lee was surprised to discover that he was already well known thanks to his role in The Green Hornet. Although it had been four years since the series ended, it was hugely popular and was regularly shown on Hong Kong television.

Bruce Lee’s breakthrough film, The Big Boss (1971 – directed by Lo Wei and Wu Chia Hsiang), marked the beginning of his meteoric rise to fame. The film’s success was unprecedented, both in Asia and internationally, introducing audiences to a new kind of action hero – one who combined martial arts prowess with a magnetic screen presence. Lee’s later films, including Fist of Fury (1972) and Way of the Dragon (1972) which Lee himself directed, showcased not only his physical abilities but also his philosophical approach to martial arts.

What set Bruce Lee apart was his commitment to authenticity. He rejected the stylized, theatrical approach prevalent in many of the contemporary martial arts films, opting for a more realistic and hard-hitting portrayal of combat. His fight sequences seldom looked choreographed. He would tense his body so that every muscle was visible, and each punch or kick seemed to have a very real impact, not just on his opponents, but on him too. As we watch, we can feel every blow. Way of the Dragon in particular deserves special mention for its iconic showdown between Bruce Lee and Chuck Norris in the Roman Colosseum. This epic confrontation rewrote the rules of action cinema, and the martial arts became cathartic and dangerous for the watching audiences. The effect has not diminished in the decades since.

While Bruce Lee undoubtedly left a mark on the genre, the 1970s were also characterized by the prolific output of the Shaw Brothers Studio.

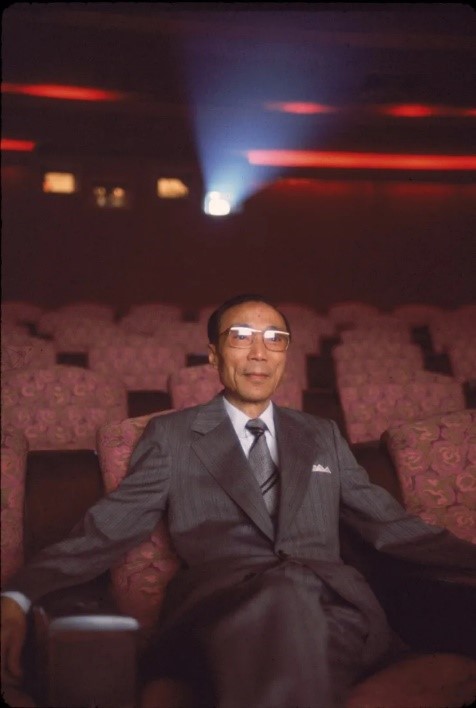

Founded by brothers Run Run Shaw and Runme Shaw in 1925, the studio holds an indelible place in the history of Hong Kong cinema, particularly for its immense contribution to the martial arts genre. Over the decades the studio became synonymous with breathtaking choreography, iconic characters, and a distinctive visual style that left an enduring mark on global film culture.

The Shaw Brothers Studio had humble beginnings, starting as a film production company in Shanghai, China. In 1925 Run Run Shaw established Tianyi Film Company with his brother Runme Shaw, and by the 1930s, the brothers had already established themselves as pioneers in the Chinese film industry. However, it wasn’t until the 1950s that the studio would make a transformative move to Hong Kong.

In 1958 the Shaw Brothers completed construction of the Movietown complex in Clearwater Bay, Hong Kong, ushering in a new era for the studio. The state-of-the-art facilities, including sound stages, editing suites, and a vast backlot, positioned the Shaw Brothers as an industry powerhouse. This move marked the beginning of the studio’s dominance in martial arts cinema, especially the Wuxia tradition, a genre characterized by tales of chivalry, martial arts prowess, and historical settings. The studio’s commitment to high production values, intricate choreography, and stylized storytelling set a new standard for martial arts films.

The brothers were very much inspired by the Hollywood studio system, and even went as far as taking the Warner Brothers logo and adapting it for themselves.

One of the key architects of the Shaw Brothers’ success was director Chang Cheh, whose collaboration with the studio spanned several decades. Chang Cheh’s impact on martial arts cinema was monumental and his films, such as The One-Armed Swordsman and a personal favourite, The Five Deadly Venoms (1978), remain iconic even to this day.

The Shaw Brothers Studio was instrumental in cultivating the careers of legendary kung fu stars who became synonymous with the genre. Actors such as Jimmy Wang Yu, David Chiang, Ti Lung, and Gordon Liu became household names, gracing the screen with their charismatic performances and martial arts gymnastics. The studio’s casting choices and talent development played a crucial role in establishing a roster of actors who would become the face of Hong Kong martial arts cinema.

Jimmy Wang Yu, known for his intense screen presence and martial arts skills, was the first martial arts star produced by the Shaw Brothers. His collaboration with the studio resulted in groundbreaking films such as One-Armed Swordsman (1967), the first film to gross over HK$1 million, and the very entertaining One Armed Boxer (1971), which Wang Yu directed himself (the scene in which the hero loses his arm is worth the price of admission). Variety called it “a Chinese actioner glossed with all the explosive trappings that make for a hit in its intended market … Exquisitely filmed and packed with colourful production values.’

The introduction of David Chiang and Ti Lung as a dynamic duo in films like Vengeance (1970) and Blood Brothers (1973), both directed by Chang Cheh, further solidified the Shaw Brothers’ commitment to cultivating kung fu talent. Their on-screen chemistry and martial arts ability captivated audiences, contributing to the studio’s continued success.

Gordon Liu, another Shaw Brothers protégé, rose to prominence through his roles in films like The 36th Chamber of Shaolin (1978, directed by Lau Kar-leung). This is one of the best films of the period and Liu excels, playing the role of a new recruit in a Shaolin Temple with furrowed brow determinism and, occasionally, as comic foil simultaneously. Despite his martial arts prowess and ability, there is a relatability to him which is very endearing. The opening title sequence, where Liu practices his moves in the rain is truly beautiful and no doubt influenced future, more prestige films such as Yi-Mou Zhang’s 2004 film Hero (check out the fight between Jet Li and Donnie Yen in the rain).

One of the defining features of Shaw Brothers martial arts films was the innovative choreography that brought fight sequences to life. The studio established a dedicated action choreography department, led by legendary choreographers Lau Kar-leung and Tong Gaai, who played a pivotal role in shaping the dynamic and visually stunning martial arts sequences that became a trademark of Shaw Brothers films.

The Shaw Brothers also implemented a rigorous training regimen for their actors, ensuring that performers had a solid foundation in martial arts. This commitment to authenticity contributed to the physicality and realism of the fight scenes, distinguishing Shaw Brothers films from other martial arts productions of the time.

The Shaw Brothers’ impact extended far beyond Hong Kong, reaching international audiences and influencing filmmakers around the world. Their films gained popularity in countries where martial arts cinema was embraced, particularly in Southeast Asia, Europe, and the United States.

In the US in particular, the Shaw Bros were very successful. Building on the reputation of Bruce Lee, Chung Chang-Wha’s brilliant The Five Fingers of Death (aka King Boxer, 1973), grossed $4.6 Million in the US and Canada.

The success of Five Deadly Venoms was attributed to its unique and atypical martial arts styles, and the fact that the Venoms were at the time “nothing like any martial arts performers US audiences had seen before” (South China Morning Post, 11 July, 2021).

Today, the Shaw Brothers Studio has an almost sentimental hold on many film fans. Quentin Tarantino for example, paid homage to the studio’s legacy in Kill Bill Vol.1 (2003). The intricate fight choreography, unique characters, and stylized violence that define Tarantino’s work generally, but in Kill Bill there are sequences which directly quote Shaw Brothers movies.

The Studio’s impact on the wider martial arts genre is immeasurable, leaving an enduring legacy that continues to influence filmmakers and entertain audiences worldwide.

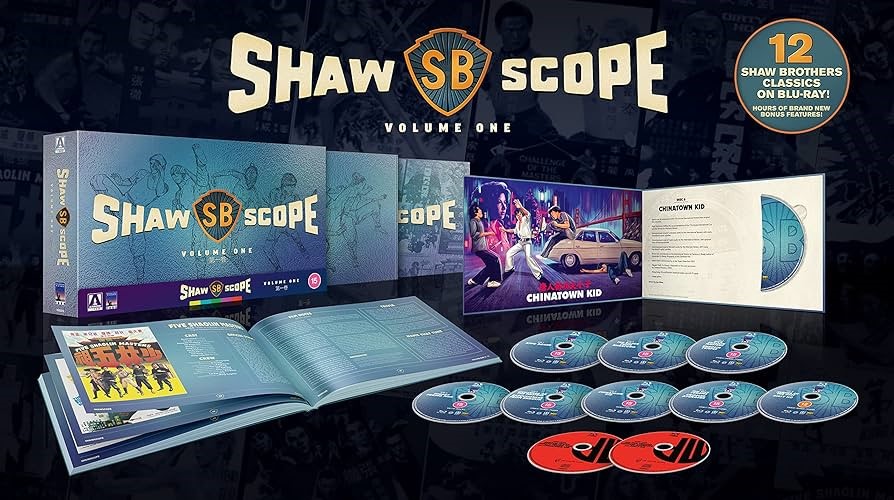

This legacy extends beyond their prolific output; they played a pivotal role in elevating martial arts cinema to an art form that transcends cultural boundaries and many of the studio’s martial arts epics remain timeless classics. This can be seen in the recent boxsets put out by Arrow Video focusing entirely on the Studio.

In retrospect, the Shaw Brothers Studio’s golden era in the 1960s and 1970s represents a cinematic renaissance that reshaped the landscape of Hong Kong cinema and the world beyond. Their directors are not widely celebrated today, although I believe many of them should be.

Chang Cheh, one of the directors often associated with the Shaw Brothers, played a crucial role in shaping the image of the traditional martial arts hero. Films like One-Armed Swordsman (1967) and Five Deadly Venoms (1978) became iconic, featuring memorable characters and intense, stylized action sequences. Chang Cheh’s emphasis on brotherhood, loyalty, and honour added depth to the genre, resonating with audiences both in Hong Kong and abroad.

King Hu started working with the Shaw Brothers in the late 1950s and made a number of important films with them in the 1960s, including Come Drink With Me. His masterpiece, A Touch of Zen (1971), however was made in Taiwan. Blending martial arts with elements of mysticism and poetic storytelling, A Touch Of Zen was an international success, demonstrating the potential of martial arts cinema to transcend mere action and incorporate deeper themes. This is something that is often forgotten in film discourse, although films such as Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2001), Yi-Mou Zhang’s House of Flying Daggers (2004) & Hero (2002) and Wong Kar-wai’s exceptional The Grandmaster (2014) have reminded international audiences of the depths hidden within the balletic fight sequences. One fight scene in The Grandmaster actually plays out as a love scene, with the two protagonists – Tony Leung and Zhang Ziyi – flirting with each other whilst exchanging blows.

The biggest competition to The Shaw Brothers Studio was Golden Harvest, a studio that has arguably had a longer lasting impact on the genre. Unlike its competitor which had been around for many decades, Golden Harvest was founded during the martial arts golden years. The studio emerged as a response to the changing dynamics of the industry, seeking to establish a new standard in film production, distribution and marketing. Raymond Chow, with his experience in the film industry, and Leonard Ho, a former Shaw Brothers executive, joined forces to create a studio that would challenge existing norms and revolutionize Hong Kong cinema.

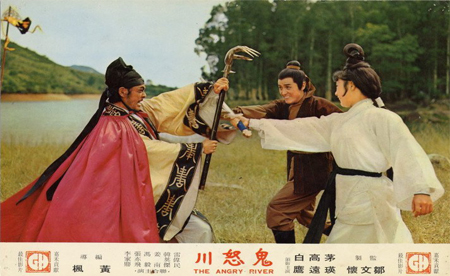

Golden Harvest’s inaugural film, The Angry River (1970), set the template for things to come. However, it was their collaboration with Bruce Lee that propelled Golden Harvest into the spotlight and changed the landscape of action cinema.

Golden Harvest’s strategic marketing and distribution played a crucial role in the global success of Bruce Lee’s films. The studio recognized the potential of the international market, particularly in the United States, and actively promoted Lee as a global action star. The success of Bruce Lee’s films laid the groundwork for Golden Harvest’s future endeavours and solidified their position as a trailblazer in the film industry.

While Bruce Lee’s untimely death in 1973 left a void in the martial arts genre, Golden Harvest set out developing a new generation of action stars. One of the studio’s significant achievements during this period was the introduction of Jackie Chan to the global stage.

Golden Harvest collaborated with a lot of emerging stars at the time, including Jackie Chan, who I will come to in a moment. Perhaps the most influential star, aside from Chan, was Sammo Hung (who also worked with Shaw Brothers). Hung worked as choreographer on The Angry River and appeared in Way Of The Dragon before establishing himself in film and TV. He even managed to get his very own US TV series with Martial Law (1998 – 2000). Another star was Yuen Biao who got his big break in 1979’s Knockabout (with Sammo Hung), establishing a formidable roster of action talent. The success of these stars helped the studio develop the genre, making the action scenes more detailed and grounded in realism, even when emphasising the absurdity of a given situation.

Hung’s contributions to Golden Harvest were integral to the studio’s success during the 1980s. His collaborations with Jackie Chan on projects such as Wheels on Meals (1984) and Project A (1983) showcased not only martial arts excellence but also a level of physicality and creativity that set a new standard for action choreography. By the time Chan made his masterpiece, Police Story, in 1985, this methodology, coupled with the success of Die Hard in 1988 set a template for action films throughout the late ‘80s and ‘90s.

Possibly inspired by the success of Bruce Lee, the studio also actively sought international partnerships, trying to appeal to a global audience. In the 1980s Golden Harvest collaborated with Hollywood studios and international filmmakers, resulting in films like The Cannonball Run (1981), with 20th Century Fox and The Protector (1985) with Warner Brothers, both featuring Jackie Chan.

Golden Harvest’s impact on the film industry extends well beyond its founding years. The studio’s ability to adapt to changing trends, cultivate talent, and engage in international collaborations has left a lasting legacy. Hong Kong cinema, particularly the martial arts genre, continues to bear the imprint of Golden Harvest’s innovative spirit.

Golden Harvest’s role in introducing Asian cinema to international audiences cannot be overstated. The studio’s films served as a gateway for audiences around the world to appreciate the artistry, culture, and storytelling prowess of Hong Kong cinema. The global success of Bruce Lee and subsequent stars nurtured by Golden Harvest paved the way for the acceptance and integration of Asian talent in the mainstream film industry.

Aside from Bruce Lee, the biggest name in Martial Arts cinema is undoubtedly Jackie Chan. After the death of Lee, the studios were desperately searching for the next big thing, and originally sort to find a duplicate successor to Lee. Chan ended up a very different performer. Unlike the stoic and intense demeanour of Bruce Lee, Chan introduced a refreshing and comedic approach to martial arts.

Jackie Chan initially worked as a stunt man and was occasionally cast in supporting roles, gaining recognition for his acrobatic and comedic approach to action. Golden Harvest recognized his potential and gradually elevated him to leading roles, allowing him to showcase his unique blend of martial arts, humour, and stunt work. Although he had been in the industry since 1962’s Big and Little Wong Tin Bar (where he was credited as Yuen Lau), it wasn’t until the late 1970s that he really made his mark as a star in films such as Drunken Master (1978), Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow (1978) and The Young Master (1980).

The fusion of comedy and martial arts was not only entertaining but also ground-breaking. Jackie Chan’s willingness to perform his own stunts, often without the use of safety harnesses, added an element of danger and authenticity that resonated with audiences. It also contributed to an increasing number of injuries throughout his career and the danger involved in his stunt work (and the injuries) were often a highlighted part of his end credit sequences.

In the later 1990s and into the 2000s, Chan and other Hong Kong stars such as Jet Li and Chow Yun Fat, travelled to Hollywood in an attempt to break into the big time. This resulted in films such as Rush Hour (and its sequels), Romeo Must Die and The Replacement Killers. Even as recent as 2020, Jet Li appeared in the Disney film Mulan.

Beyond Hollywood, the influence of Hong Kong martial arts cinema extended to different parts of the world. European audiences, particularly in France and Italy, developed a strong affinity for kung fu films. Directors like Jean-Pierre Melville (in philosophy if not action – check out Le Samourai and Le Cercle Rouge) and Quentin Tarantino openly acknowledged their admiration for the genre. In the ‘80s and ‘90s, action stars such as Jean Claude Van Damme and Steven Seagal adapted the Hong Kong style to American cinema.

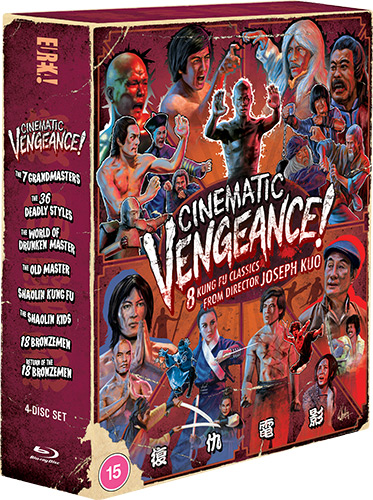

Today, Blu-ray distribution companies such as Arrow Video, Eureka and 88 Films, have released a slew of movies from the Golden Period, opening up the genre to a new generation of audiences.

This can only be a good thing, as there is a wealth of entertainment out there waiting to be watched.

The importance of this genre, and in particular it’s reign of success during the 1970s, cannot be overstated. It’s often ignored yet is massively influential. It’s a genre that helped a country redefine itself, to rediscover its heritage after the massive upheavals of colonialism, war, and Maoism, and to shape the way the Hong Kong people, and later China itself, saw themselves going forward. In doing so, it helped reshape filmmaking throughout the world.