Kong Jubilee: A 90th Anniversary Celebration – Part 2.

Resurrecting Kong.

Godzilla would get its own quickie sequel, Godzilla Raids Again (1955), which would introduce the element of another giant monster for Godzilla to battle. These giant monsters would be referred to as “kaiju” (meaning “strange beast”) in Japan, and that would be a phrase for them that would catch on elsewhere in the world. While Ishiro Honda would not return to direct, opting to instead helm a regular-sized monster movie, Half Human (1955), a story about an abominable snow man, that in recent years Toho would bury and refuse to acknowledge for its insensitive portrayal of Japan’s indigenous Ainu people. Honda would return to creating larger than life monsters with Rodan (1956), a film that featured a pair of enormous devilish pterosaurs. Eiji Tsuburaya would return to create the special effects, and Haruo Nakajima would once again perform most of the suit acting. Rodan would be a box office hit, which would beget even more kaiju movies directed by Honda.

Back in America, the trend would continue with films about giant creepy-crawlies like Them! (1954), which is about giant ants, and Tarantula! (1955), which, I’m sure you don’t need me to tell you, is about a giant tarantula. While often entertaining, it wasn’t unusual for these films to have budgets leaning toward the shoestring end of the spectrum. For example, on It Came from Beneath the Sea (1955), money was so tight that Ray Harryhausen made the decision to create the film’s giant octopus with only six tentacles (or maybe it’s just a sexapus), so he could animate its movements in less time. Most of these were unabashed B-grade pictures, and certainly films like The Giant Claw (1957), The Deadly Mantis (1957), and The Monster That Challenged the World (1957) could be enjoyed on that level, but they were hardly well respected films.

The influence of King Kong continued to be felt strongly throughout the decade. One of the more obvious examples being 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957), which features another Harryhausen creation, a Kong-like dinosaurian alien. The monster would meet a tragic end, gunned down and falling from the Colosseum in Rome, instead of the Kong’s Empire State Building in New York. That film ends with the rhetorical question, “Why is it always, always so costly for man to move from the present to the future?”

It was amidst the surplus of giant monster movies that Merian C. Cooper began toying with the idea of revisiting his giant terror ape. He’d consider dusting off his old side-quel idea, now calling it The New Adventures of King Kong. That idea would be mostly left behind in favour of a straightforward remake the original King Kong with the grandiose title of The 8th Wonder, with maybe a few elements of the side-duel pitch blended into it. Regardless of the exact story details, Cooper’s intent was to use cutting-edge technology to refresh the giant ape’s spectacle and create a film that would tower over its contemporaneous monster movies. A true grade-A picture, Cooper intended for this revival to be shot in colour and for the widest screen imaginable.

Cooper had played an instrumental role in developing a truly spectacular widescreen process called Cinerama. It required the use of a special three-lens camera that would run three strips of film simultaneously. To be shown in its full glory involved the use of three synchronized projectors and a massive curved screen. Only a handful of films would ever be created to fully utilize the true 3-strip format, most of which were very light, travel documentaries. That included the debut feature This is Cinerama (1952) and Seven Wonders of The World (1956), both of which Cooper produced, and the latter of which seems like it would have been an appropriate precursor to Kong, the Eighth Wonder of the World.

Willis O’Brien was once again recruited for the special effects for the Cinerama Kong. It would have been interesting to see how he would have tackled the technical challenges of the format, but the film would not come to be. Partly due to its ambitious scope and technical complexity, the idea didn’t pick up enough momentum. Cooper would once again have to set Kong aside, preoccupied with other projects like producing his ambitious final collaboration with John Ford, The Searchers (1956). It’s a shame because the larger-than-life format would have likely bestowed on Kong a worthy grandeur that would have cast all other 1950s giant movie monsters in his shadow.

Unfortunately for Willis O’Brien, the Cinerama Kong would be one of many films that would fall apart in his later years. This led to a prolonged career slump. O’Brien was a master of his craft, but his time-consuming stop-motion process often negated him in time-is-money-conscious studios, wary of hiring him, especially when there were alternatives to be found in young and less experienced animators, eager to prove themselves on films with little money and time available to them.

O’Brien took to pitching his own ideas to studios in the hope of drumming up stop-motion work for himself. Some would have been very much in the vein of King Kong, like Baboon: A Tale About a Yeti, which would have featured a very Kong-looking take on the mythic Himalayan creature. There was even some talk of reviving War Eagles, a project that Ray Harryhausen would continue to try to breathe life into for years after. Nearly all of O’Brien’s pitches were rejected or would fall apart in development. Ray Harryhausen would say, “He had so many projects fall through before they reached the screen… How he survived these disappointments, I’ll never know.”

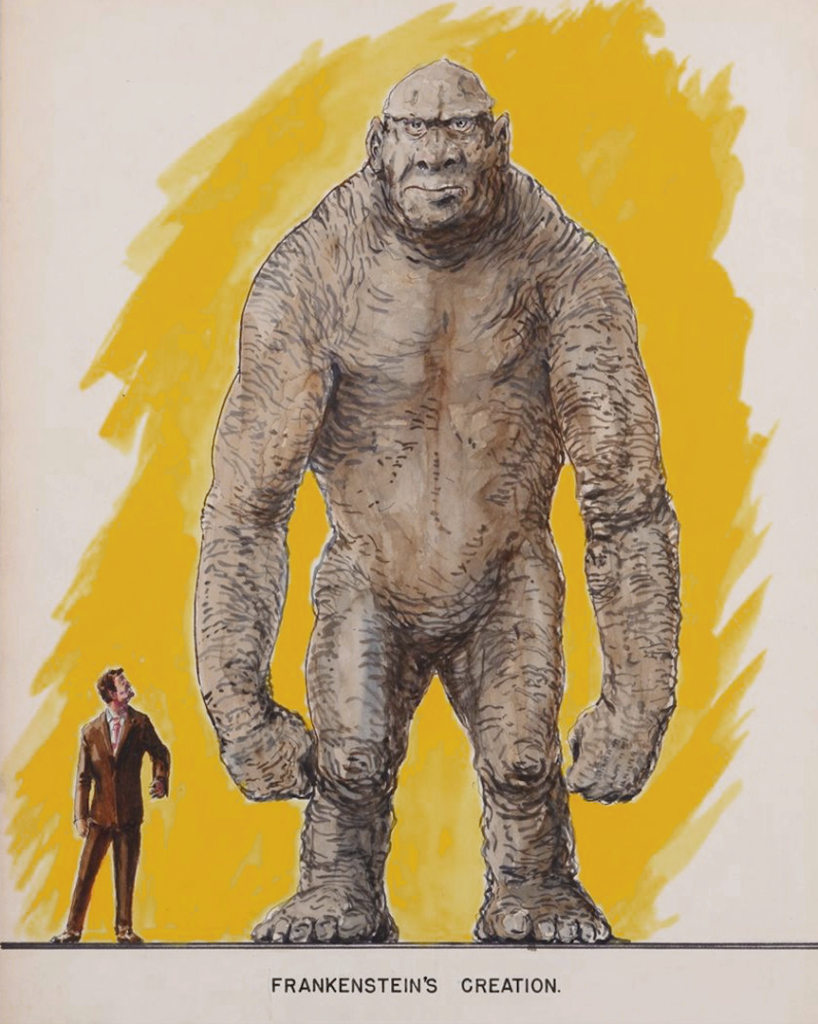

There was an O’Brien pitch that would eventually lead to something. It was an idea for a new sequel to King Kong, entitled King Kong vs. Frankenstein. That title was later changed to King Kong vs. The Ginko and then to King Kong vs. Prometheus to avoid any potential legal conflict with Universal Pictures’ series of Frankenstein films, even though the character was in the public domain. The plot would have revolved around Kong being brought to San Francisco for a heavily promoted fight with Frankenstein’s creation, much like two boxers or wrestlers. O’Brien’s take on Frankenstein’s monster would have looked much like a hairless Kong, a grey hulk with elephant skin, that would have been controlled through a remote by the modern descendant of Victor Frankenstein. This version would have more closely resembled the mythic Czech Golem than the Universal Pictures interpretation of Frankenstein’s monster that Boris Karloff had made iconic.

RKO hooked O’Brien up with a producer named John Beck to develop the King Kong vs. Frankenstein concept, and George Worthing Yates, who had written Them! and It Came from Beneath the Sea, was brought in to flesh out the screenplay. O’Brien made a deal with Beck that would allow the stop-motion master to do the special effects should the film get made. Beck would prove to be less than trustworthy, quietly cutting O’Brien out of the pitch and essentially stealing the project out from under him. Beck peddled the script to every major studio in Hollywood, all of whom rejected the idea. However, the pitch would attract interest from an unexpected source, a Japanese film studio called Toho.

Kong The Kaiju.

Toho was the very same studio that had been responsible for Ishiro Honda’s string of kaiju films, including Godzilla, Rodan, and then most recently, the hit film, Mothra (1961). In contrast to some of the Hollywood studios, which regarded their giant monster movies as little more than profitable embarrassments, Toho took pride in their monster films. They had brought the studio great success and recognition, and apparently for a time phone calls would even be answered with, “Toho, home of Godzilla.” The opportunity to bring the authentic King Kong into their rapidly growing franchise of monster movies was too enticing to pass up. John Beck sold Toho the rights to make Kong vs. Frankenstein for $220,000 dollars. This was not an inconsiderable sum for the Japanese studio, which was much smaller in scale than the average Hollywood studio. It was to be a high profile production for Toho and would even be designated to celebrate the studio’s 30th anniversary.

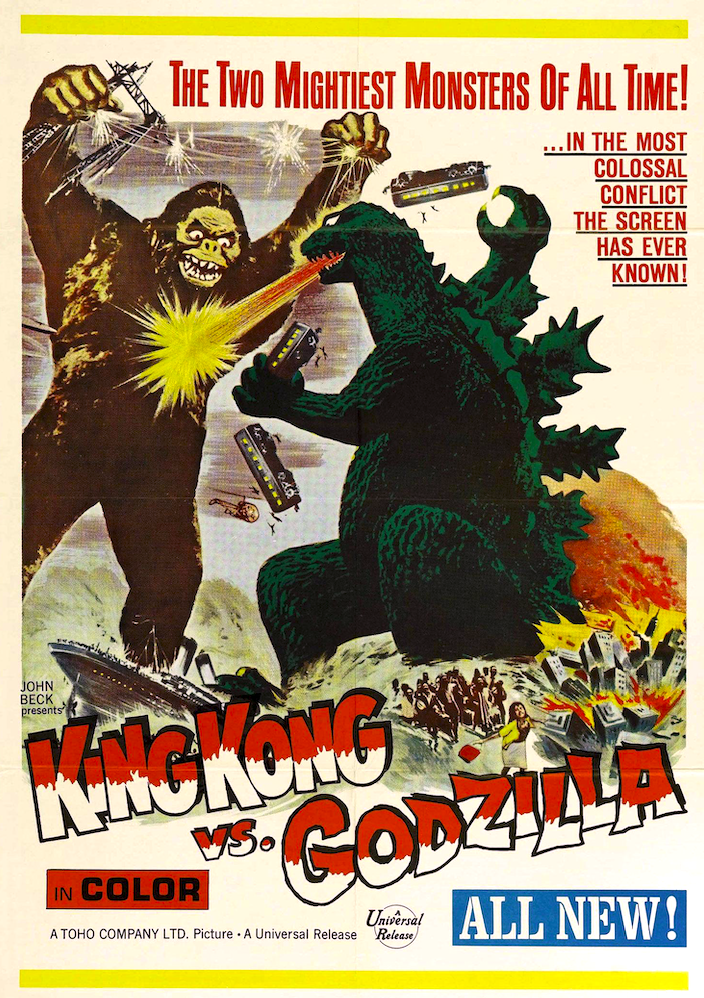

The decision was made at Toho, that rather than fight Frankenstein’s monster, King Kong would fight one of their own monsters, Godzilla.*1 It may have been a commercially prudent decision, but there’s also an inescapable sense that it was inevitable that Kong should duke it out with the young upstart dinosaurian monster. Whether it represented a clash of nations or a clash of generations, there’s an intuitive symbolism to seeing Kong and Godzilla fight that I think a fight with Frankenstein’s monster just wouldn’t have had. They would also both be making their first appearance in both colour and widescreen.

Shinichi Sekizawa, the enigmatic screenwriter who had just written Mothra, was brought in to completely overhaul the script. Though a few aspects of Kong vs. Frankenstein would carry over, including the fight promotion aspect of the story, which was given more of a satirical spin by Sekizawa. Perhaps the strangest thing to carry over are the inexplicable electrical powers that King King would now have, inherited from Frankenstein’s monster. So in a way, it might be said that the screenplay itself was something of a Frankenstein’s creation.

RKO also had a few demands, including that at one point Kong must snatch up a beautiful woman and ascend a tall building with her. This time the ingénue in the palm of Kong’s hand would be Mie Hama, portraying a character named Fumiko. It’s a diversion from the main story, but perhaps an understandable one considering Kong’s iconography.

The final story would revolve around an advertising executive at a pharmaceutical company named Mr. Tako (played by the estimable comic actor, Ichiro Arishima) who gets the idea to capture King Kong and use him for publicity. While that plays out, a submarine inadvertently unleashes Godzilla from an iceberg (in which the monster had been trapped at the end of Godzilla Raids Again). Godzilla sets out on a path of destruction, and undeterred by conventional weapons, it becomes obvious that King Kong is the only thing that can stop it. It all builds to a climactic showdown between the two monster on Mount Fuji.

Ishiro Honda returned to direct Godzilla once again, but Toho mandated that the film have a child-friendly tone due to the monster’s popularity with young audiences. The original Godzilla was a wholly serious, adult-oriented monster film, so Honda understandably bristled at this change in direction. However, as someone whose first proper introduction to King Kong was by watching King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962) on videotape as a child, I can say that Toho may have been onto something with the more child-friendly direction that Honda eventually yielded to. On this dramatic change in tone and target audience, he would say, “Personally, I didn’t want to do it, but the company demanded it. When you have to do it, you have to do it. I did the best I could with it, and Mr. Tsuburaya did his best as well.”

Eiji Tsuburaya had committed to doing special effects work on other films, which should have prevented him from working on King Kong vs. Godzilla, but upon hearing that Toho was making a film with King Kong, he dropped his other commitments to be able to work on the monster that inspired him to become a special effects artist. He had some hope of being able to use stop motion animation for the majority of the film’s effects, but unfortunately, because the rights to Kong had cost more than half of the film’s allotted budget, Tsuburaya was left with little more than a shoestring to work with. Once again, suitmation would be Tsuburaya’s method for bringing monsters to life, with only a tiny bit of stop motion animation being used in the final film, which actually feels a little out of place after becoming so accustomed to seeing the suit performances for the majority of the film. To contrast the film’s suits and special effects with the work Tsuburaya had done on other films around the same time, it becomes apparent how scant his resources were, though he clearly makes the most of them.

The limited budget would also impact the film’s shooting locations. Honda had hoped to film the scenes set on Kong’s island in Sri Lanka, with Sri Lankan performers playing the indigenous people of the island. When this proved to be too expensive, the compromise was to shoot on the Japanese island of Oshima, near Tokyo. Japanese performers in brown makeup would be used to portray the islanders, that, in conjunction with some stereotypical depictions, would result in the most unpleasant aspect of the film.

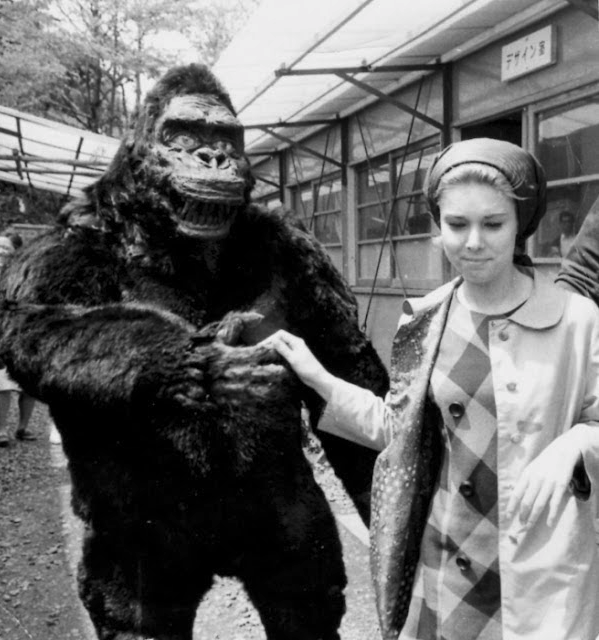

Another compromise would come at the request of RKO, that this iteration of King Kong not look too much like he did back in 1933. Perhaps this was a way of trying to distance the Japanese production from their property, but it’s uncertain. So Kong’s design was tweaked, with macaques as a major source of inspiration, giving him lighter fur and a more pronounced maw. The end result has some obvious shortcomings, like, for instance, the inconsistent use of arm extensions to give more gorilla-like body proportions, though I must say that I like Kong’s new look for the 1960s. His bulky build, distinctive face-sculpt, and tombstone-toothed grin are instantly recognizable. Incidentally, one of the most striking features of Kong’s look, the occasionally whited-out eyes, was unintentional, just a byproduct of the mask fogging up. I always find that the white eyes give Kong a bit of a demonic or ghoulish look that might even be in line with “Yokai,” the monstrous spirits of Japanese folklore.*2 King Kong would also be scaled up considerably to stand toe-to-toe with the towering Godzilla, both figuratively as well as being a necessity of them both being performed by actors in suits. Kong now towered over buildings that would have towered over him three decades earlier.

Kong would also undergo some changes in characterization. While this particular portrayal does lean towards something more buffoonish, it is notable that for the first time, Kong would be unambiguously the hero of the film. His opponent, Godzilla would also see a change in personality, occupying a somewhat awkward place in his evolution. Godzilla had yet to take on the more heroic defender-of-Earth persona that would come in following films, but he’s not the absolute terror he was in his two previous solo films. Rather, he plays the role of “the heel,” to Kong’s “face,” to borrow wrestling terminology.

Haruo Nakajima would once again perform Godzilla. Sown into the King Kong suit would be Shoichi Hirose, who was one of Nakajima’s peers, and the two had previously appeared together as bandits in Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (1954). In addition to bringing a bulky physicality to Kong, Hirose would claim that he studied footage of real apes to help add some personality to his performances, but would later admit that that wasn’t really the case. Still, he would give Kong some distinct gestures, like scratching himself casually or tilting his head with curiosity. Without a fight choreographer, many of the details of Kong and Godzilla’s fighting would come down to the decisions of the suit performers themselves, incorporating wrestling and judo moves into the brawl between the two titanic monsters. One of the most impressive moments in the film from a stunt perspective would be when Hirose, wearing the already heavy King Kong suit, flips the Gozilla suit, which weighed as much as a man, over his head. It all adds up to an exhilarating wrestling match between the two monsters, which ends with King Kong as the tentative winner.

Despite the budgetary and creative limitations, the final film radiates a special sort of enthusiasm and imagination, with many memorable moments, like Kong’s fight with a giant face-clinging octopus (in a moment that recalls It Came from Beneath the Sea and prefigures the famous “face hugger” monster of 1979’s Alien), or the comical flailing of Godzilla when Kong rams a tree down the other monster’s throat, or Kong’s surprise at Godzilla’s radioactive blast. The final film is inarguably a very entertaining and admirable work of pop art. Audiences would respond strongly to it, and King Kong vs. Godzilla would prove to be a massive box office success when it opened in Japanese theatres in 1962. In fact, accounting for tickets sold, or adjusting for inflation, it might even today still be considered the most successful film to feature Godzilla. Its popularity would also lead to the “vs.” format becoming a staple of the giant monster genre forever after.

Presumably with dollar-signs in his eyes, producer John Beck slapped together a shoddy alternate version of the film to be released to American audiences the following year. Not all would be pleased to hear of this release. Upon discovering that his trust in John Beck had been betrayed, Willis O’Brien set out to sue the producer, but was unable to come up with the financial resources for a legal battle. Many have felt that the stress from the whole ordeal led to O’Brien’s death from heart failure a few months before the American release of King Kong vs. Godzilla. Merian C. Cooper would also be shocked to find out that RKO asserted that they and not he owned the rights to his creation, leading to a protracted legal dispute. He was understandably disdainful of the film itself, writing in a letter, “I was indignant when some Japanese company made a belittling thing, to a creative mind, called ‘King Kong vs. Godzilla.’ I believe they even stooped so low as to use a man in a gorilla suit, which I had spoken out against so often in the early days of King Kong.”

With the alternate American version came a rumour that would persist even into the ‘90s when I first saw the film. It was said that in the Japanese version, Godzilla was the one to come out on top. Of course that wasn’t true, but it may have been an easy assumption to make, considering that even though Kong would be declared the winner, the outcome feels a little less than conclusive. It leaves the lingering feeling that the two seemed destined to have a rematch.

Perhaps that lack of conclusiveness was because Toho held hopes of making a sequel. With the massive success of King Kong vs. Godzilla, Shinichi Sekizawa was quickly brought in to write a direct sequel, which would have been titled, “Continuation: King Kong vs. Godzilla.” The plot Sekizawa came up with was quite interesting too; a rescue team is sent to the site of a crashed airplane, discovering a lost city where Kong has taken up residence while caring for the only survivor of the plane crash, a small child. While Kong is distracted fighting a giant scorpion, the team rescues the child and takes him away. However, Kong has bonded with the child and chases them back to civilization, where it’s decided that the best way to stop his rampage would be to resuscitate Godzilla, who has washed ashore and turned into a tourist attraction. It would have had its share of memorable scenes, especially one where Kong sees a child and picks them up, much to the mother’s horror, and as he realizes that it’s not the child he’s searching for, there would have been an intense moment of suspense recalling the woman mistaken by Kong for Ann Darrow before being dropped to her death in the original King Kong, though this time (in what would have again been a more child-friendly film), Kong would have gently put the child back down. While this sequel would never end up being made, Toho was still eager to use King Kong again.

Toho had hoped to produce a series of five solo King Kong films, but RKO was only willing to grant them the rights to make one more. With that option, Toho struck a deal with Rankin/Bass, the animation studio that had achieved notoriety with the beloved stop motion animated television movie, Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer (1964). Toho would create a King Kong film that was meant to tie-in with the Saturday morning cartoon, The King Kong Show, which Rankin/Bass was then currently producing, and sourcing their animation in Japan. The solo film was proposed to be “Operation Robinson Caruso: King Kong vs. Ebirah,” and would have had Kong square off with the popular giant moth Mothra, who had just defeated Godzilla in Godzilla vs. Mothra (1964), as well as fight a giant crustacean named Ebirah. Rankin/Bass rejected this pitch for really having nothing at all to do with the cartoon. However, the film would end up being made, only without King Kong. Ebirah, Horror of the Deep (1966), as it would eventually be titled, would remain largely the same, only now with Godzilla as its principal monster instead, who begins the film seemingly expired after his defeat in Godzilla vs. Mothra before being brought back to life by a bolt of lightning. The intended use of Kong is most likely why Godzilla seems a little out of character during the film, at one point even being mesmerized to sleep by the beauty of an islander woman, which is much more the sort of thing you’d expect to see from King Kong.

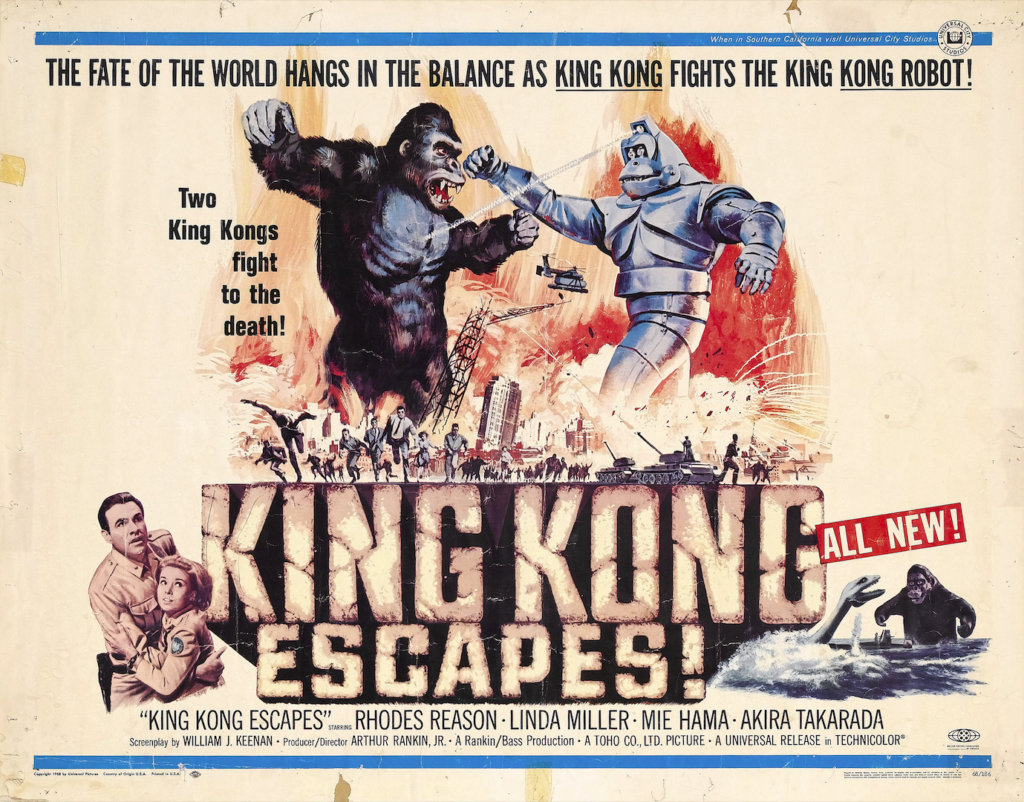

Eventually, Toho pitched a concept that met with Rankin/Bass’ approval. This would lead to the creation of King Kong Escapes (1967), with Honda returning to direct and Tsuburaya returning for special effects, though it would be their final time working together (with Tsuburaya becoming more focused on television work before passing away in 1970). It’s a film that would see Kong face off against his strangest opponent yet, a robotic doppelgänger called Mechani-Kong (which foreshadows Godzilla’s most famous antagonist, Mechagodzilla, who would make its first appearance seven years later). In the battle between the primitive Kong and his technological lookalike, there’s at least some subtext there for technical advancement not always resulting in something better, which may be a theme worth keeping in mind when considering how linked King Kong is with the technological advancement of special effects.

Mechani-Kong is the invention of the villainous, cape-wearing Doctor Who (also sometimes translated as Dr. Hu). While he isn’t related to the popular British television show character of the same name, Hideyo Amamoto, who wonderfully plays the outrageous character, is certainly eccentric and dressed in a dapper enough manner so as to draw a comparison. He’s also assisted by the chilly Madame Piranha, who is played with wonderful aloofness by Mie Hama, who seems to be a much better fit for this sort of character than the damsel in distress she played in King Kong vs. Godzilla, and who would that same year appear in the James Bond adventure You Only Live Twice). The two villains scheme to use Mechani-Kong to extract a rare and dangerous element, but when the machine fails, they set their sights on the true King Kong.

King Kong Escapes would also see the introduction of a new leading lady for King Kong, a submarine nurse named Susan Watson. Susan would be played by Linda Miller, an American who had been working as a model in Japan, appearing in numerous ads and commercials. She had been cast after Arthur Rankin (of Rankin/Bass) had seen her in one. Even though her performance would ultimately be dubbed over, and her only other film credit would end up being a small role in cult filmmaker Kinji Fukasaku’s science fiction horror film The Green Slime (1968), I think Miller’s significance to Kong’s history is not to be underestimated. Susan would have a much more reciprocal relationship with Kong than Fay Wray’s Ann Darrow had, reflecting a general shift in attitudes brought about by second-wave feminism in the 1960s. She’s a character bold enough to talk Kong down when he’s doing something wrong, a personality trait that would stick with Kong’s leading ladies forever after.

Kong himself looks a little improved this time too. This time Haruo Nakajima would don the suit; a heavily modified version of the one used in King Kong vs. Godzilla with better proportions and a new face. Also, without the enormous Godzilla to fight, Kong would be scaled down to about half the size he was in King Kong vs. Godzilla. Even then, he’s still considerably taller than he appeared in the original film.

Kong meets Susan after coming to her rescue from a dinosaur, the vicious Gorosaurus, which I have to say is one of my favourite classic Toho supporting monsters. Kong trounces Gorosaurus in that way that he tends to with dinosaurs, breaking its jaw as the finishing move. Apparently Toho had okayed the use of some blood for Gorosaurus’ defeat, but Tsuburaya and Honda pushed back. Tsuburaya would say, “These movies are for kids. It’s nonsense. Why would anyone enjoy showing them blood?” Honda agreed, and so Gorosaurus would instead spew bubbles.

Even more exciting is the showdown between King Kong and Mechani-Kong, which leads to the mechanical ape climbing up Tokyo Tower with Susan in hand. Kong ascends the tower to rescue her. When she’s dropped, Kong manages to catch her and set her down (a suspenseful moment that would be redone in variation in later Kong films). He battles his mechanical foe at the very top of the tower, which leads to Mechani-Kong’s fall and destruction.

King Kong Escapes is a delightful film. It’s easily the equal of any of Godzilla’s cinematic outings in the 1960s. Watching it, it might be easy to be reminded of the tone of the 1960s Batman television series. The ending leaves you wanting more; Kong beating his chest in his signature fashion after destroying Dr. Who’s ship and killing him in the process, and then wandering out to sea to return home to his island, with Susan calling after him, “Kong! Kong! … King Kong!” She’s told by her commanding officer, “He’s going home. I think he’s had enough of what we call civilization.”

Kong may have had enough of Japan, even if Japan hadn’t had enough of Kong. Toho made one more bid for the rights to Kong, in the hope that he might play a role in the extravaganza, Destroy All Monsters (1968). It could have been a fitting farewell for Kong’s time spent in Japan, but that would not come to fruition (though Gorosaurus would make an appearance, destroying the Arc de Triomphe in Paris). Considering the passion and creativity that King Kong inspired, it’s reasonable to be left with the feeling that Kong’s tenure as a Toho kaiju was all too brief.

King Kong II.

Kong would indeed return to his home country, even if his journey took a few years before he’d finally arrive.

There were other international film studios that had hoped to obtain the rights to Kong. The most notable would be Hammer, the British production company best known for its fresh and colourful takes on classic monsters like Dracula and Frankenstein’s creature. Hammer approached RKO (which at that point had stopped producing films and was owned by General Tire) several times over the course of the late 1960s in the hope of remaking King Kong. Hammer even intended to bring aboard Ray Harryhausen to create the stop motion effects for it, which instead led to the creation of the film One Million Years B.C. (1966). Ultimately, RKO rejected the idea of a King Kong remake altogether. You can at least see some test footage created by stop motion animators Jim Danforth and David Allen. Once the film fell through, their test footage would be repurposed for a 1972 Volkswagen ad. It’s an ad that would eventually be given a nod to in a fake car advertisement in Paul Verhoeven’s 1987 sci-fi film RoboCop, a film that featured the stop motion work of Phil Tippett, who had been mentored by Danforth.

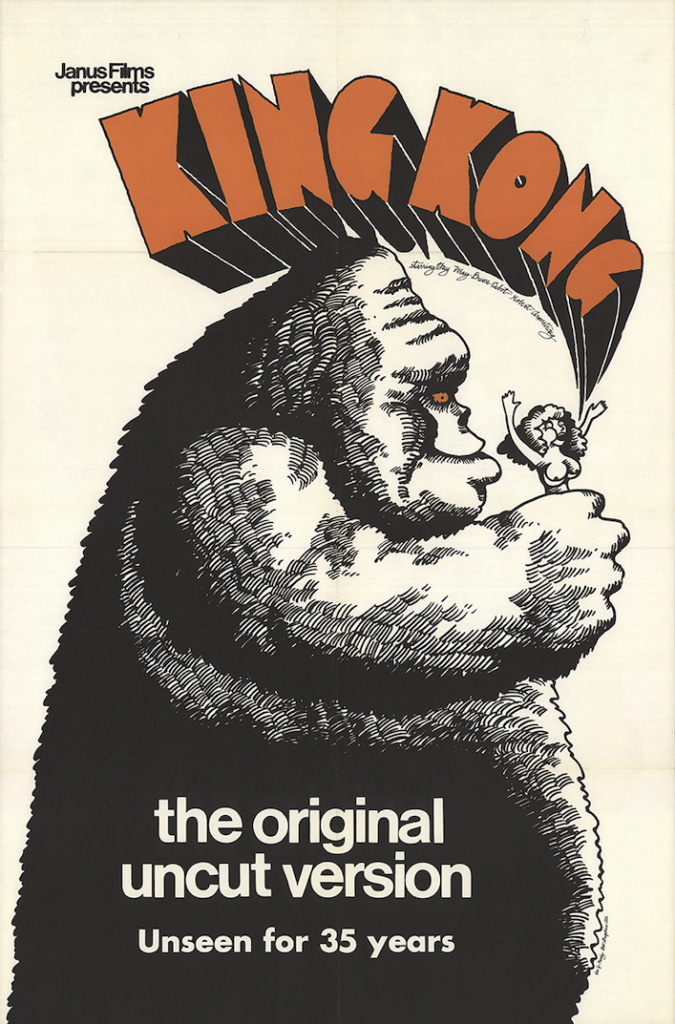

The 1960s also saw the dissolution of the morality code that had kept a stranglehold on the content of Hollywood films and necessitated the censoring of King Kong for its rereleases. A wave of films and filmmakers pushed back against its artistic boundaries, and the code would be entirely abandoned by 1968. The code would be replaced with the Motion Picture Association of America film rating system that continues to this day. Consequently, 1969 also saw the first restoration of King Kong, released by Janus Films, which finally restored the lost censored scenes that audiences hadn’t seen for 35 years. In addition to being an important milestone in the film’s preservation, it was perhaps also a reminder to popular culture that King Kong was not just entertainment for children, but could hold a more adult appeal as well.

Merian C. Cooper passed away in 1973. While his attempts to assert legal ownership over King Kong were unsuccessful, from the perspective of film producers, his death may have been regarded as the removal of an obstacle to more openly exploiting the license to King Kong. That may have sounded a little unlikely at that point in time, because King Kong may have seemed like a dusty, 40-year-old property. The giant monster movie trend was mostly passé by then, and in 1975 Ishiro Honda would direct his final kaiju movie, Terror of Mechgodzilla. However there would soon be reason for renewed interest in King Kong as an intellectual property.

With the 1975 release of Steven Spielberg’s great white shark thriller Jaws, the era of the blockbuster had arrived. A terrifying and exciting film about an unusually large animal on a violent rampage suddenly looked very commercial to Hollywood. There would be not one but two competing attempts at remaking King Kong by major Hollywood studios.

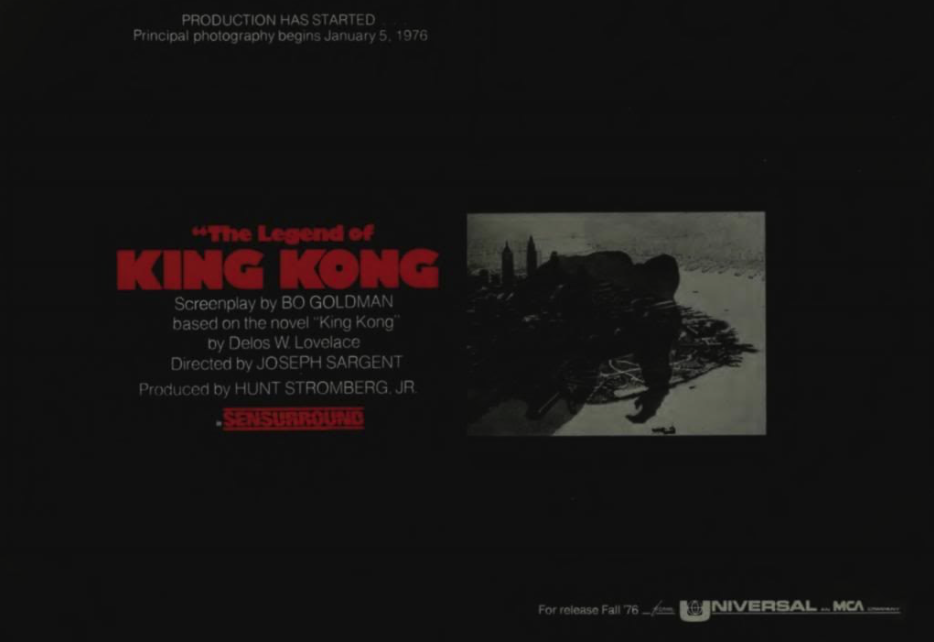

Universal Pictures and Paramount Pictures both held the belief that they alone held the license obtained from RKO to create a remake of King Kong. Naturally this led to a legal battle, resulting in a surprising outcome. Judge Manuel Real determined that in fact both studios could make their own King Kong film, though only so long as rather than the film itself, Universal base their version on the tie-in novelization for the original film, written by Delos W. Lovelace, which had slipped into public domain. Judge Real also determined that in fact Cooper’s estate did own the basic story and characters of King Kong, a posthumous recognition of Cooper’s artistic rights. Shortly after, the estate made a quick buck by selling what they owned to Universal.

With both studios okayed to make their own film version of King Kong, what followed was a sort of game of chicken between them. The basic notion was that whichever could get their version of King Kong out first would legitimize it in public perception and make the other’s version irrelevant.

The Universal version would have been titled The Legend of King Kong and would have kept the story set in the 1930s. The film would have also utilized the same characters as the original, and it seems Peter Falk was a lock to play Carl Denham, which would have been a wonderful bit of casting. Even with the novel as the official basis, the intention was to closely parallel the original film, with a few reasonable deviations for the sake of character, such as having Ann refuse to participate in Denham’s Kong Broadway show in the final act. Joseph Sargent was set to direct, hot off of his masterful thriller, The Taking of Pelham One Two Three (1974).

On the other end of the game of chicken between prospective Kong productions, was Paramount’s version, which was in the hands of Italian producer-extraordinaire Dino De Laurentiis. What differentiated his approach was that he intended to bring the story forward into the 1970s, updating its concept and themes. De Laurentiis, who was inspired to take on the project by his daughter’s love for the original, believed audiences would respond to the tragic nature of the monster. He’d famously say, “In Jaws, when the shark die, nobody cry. When the ape dies, everybody cry.”

Writer Lorenzo Semple Jr. was hired to develop the screenplay. He’s best known for his work on the 1960s Batman television series, though in the mid-1970s he was coming off a string of thrillers; The Parallax View (1974), The Drowning Pool (1975), and Three Days of the Condor (1975). On the new approach to King Kong, he would say, “We made a very deliberate attempt not to be anything like the original movie in tone or mood. Dino wanted it to be light and amusing rather than portentous. I don’t think the original was meant to be mythic. The original King Kong is extremely crude. I don’t mean it’s not wonderful. It was remarkable for its time, but it was a very small backlot picture. We thought times had changed so much that audiences were more sophisticated.”

The decision was made to push De Laurentiis’ King Kong into production as quickly as possible, something that ultimately hindered the quality of the final film, but was what was needed to make Universal blink. The Paramount version would be the only King Kong film produced in the 1970s, though Universal would hold out hope to one day realize their own King Kong remake.

De Laurentiis had initially approached a post-Chinatown (1974), pre-scandal Roman Polanski to direct, but the Polish auteur showed little interest in the giant terror ape. So instead John Guillermin, who had previously directed the hit disaster film, The Towering Inferno (1974) would be brought in to direct, and his approach to the story would reflect more of a disaster film sensibility than the horror-thriller approach of the original film. There would be numerous changes made to bring the story of King Kong into a new era.

The 1970s energy crisis would fill in for the milieu of the Great Depression that the original had. The plot being kicked off by an oil tycoon who sets out on an expedition to a perpetually misty island in the hope of finding a natural resource to exploit. While Universal’s deal with Merian C. Cooper’s estate prevented Paramount from using the characters of the original film, this character is a rough analogue for Carl Denham in this version, though he’s named Fred S. Wilson. He would be played with wonderful detestability by Charles Grodin, with René Auberjonois as his sidekick. Grodin would comment on what attracted him to the film, “Kong is really the pure, natural animal when he is in his jungle habitat. His fate is to be exploited by men who put him in bondage and carry him off to a hostile environment. If you had gone out to make a film about how man has exploited and polluted his streams and atmosphere, and you did it in a documentary style, no one would come out to see the film. But in doing King Kong, I realized, I had a chance to work in a film with the potential of being seen by more people than any other film in the history of the business, and it could say something.” In an echo of King Kong vs. Godzilla, Fred S. Wilson will come to see Kong as an opportunity to promote his company.

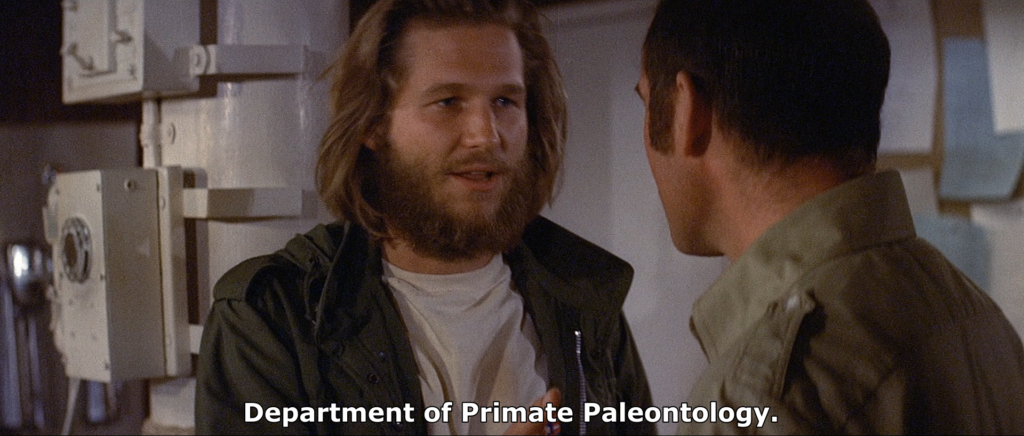

Jeff Bridges plays a maverick primatologist and conservationist named Jack Prescott, who is a reworking of the Jack Driscoll role from the original. He stows away on Wilson’s ship, drawn by rumours of an enormous humanoid’s existence. It may be largely to Bridges’ credit, but as someone who doesn’t typically like the male human part of Kong’s love triangles (maybe I just identify with the monster a little too much), I have to say that I really like this version of the Jack character. He’s someone who’s described as a “hippie,” and his place in the film might reflect both the broader new wave of environmentalist activists that emerged in the 1960s.

In that way, Jack Prescott represents the changing attitudes towards gorillas, with biologist and conservationist George Schaller being a likely source of inspiration for the character. At the age of 26, Schaller traveled to the Virunga Volcanoes in central Africa to spend two years studying mountain gorillas in a way that had never really been done before, leading to the publication of his 1963 scientific book, The Mountain Gorilla: Ecology and Behavior, followed by his more personal and narrative 1964 book, The Year of The Gorilla, both of which had a massive impact as far as opening up the public’s eyes to the un-monstrous true nature of gorillas. He also brought attention to the fact that mountain gorillas were facing imminent extinction, estimating that there were only about 450 left in the wild.

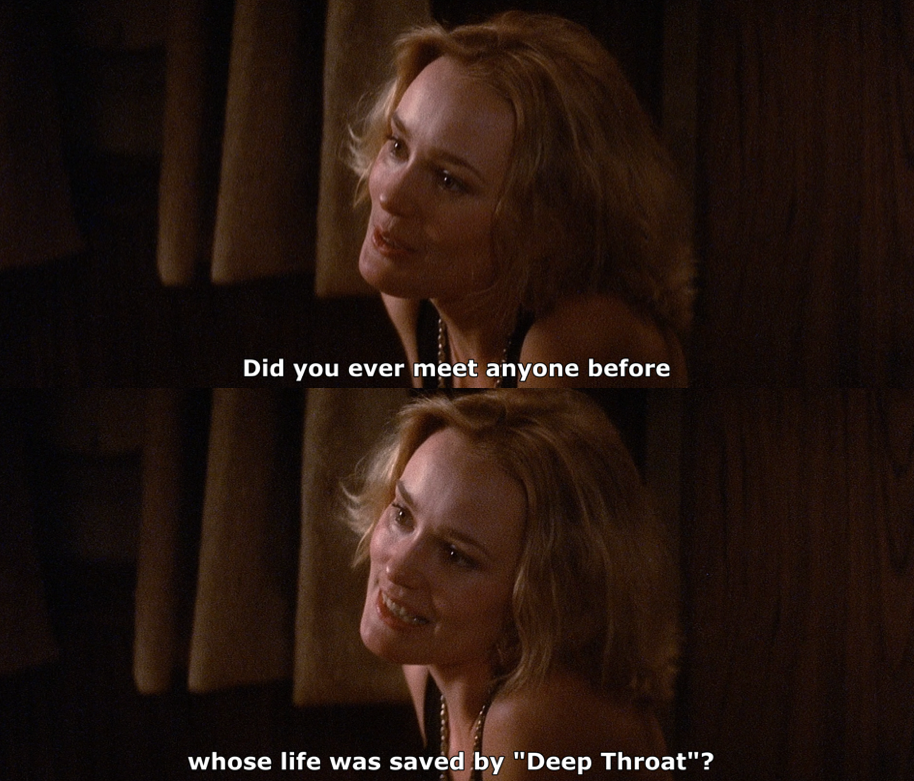

The expedition to Kong’s island come across an unconscious woman in a lifeboat on their way to the island, whom Jack quickly saves. When she comes to, she reveals herself to be a model self-named Dwan, “like Dawn, except I switched two letters.” You know, to make it more memorable.” She was being brought on a yacht to Hong Kong by a sleazy producer to play a role in a movie, and while it’s never exactly stated, there’s some implication that it may have been some sort of exploitative situation. Through happenstance, she was saved from the yacht exploding by the famous pornographic film Deep Throat (1972), which was why she was adrift in the lifeboat. These would be details easy to gloss over, but I think they’re a tip-off to an interesting extension of the original film’s complicated themes related to exploitation and show business.

Dwan is played by a model in her first acting role, Jessica Lange. Today, Lange is widely and rightly recognized as a powerhouse actress, but it’s not really a secret that, for King Kong, she was hired primarily for her appearance. De Laurentis would even turn down much more experienced actresses, and somewhat infamously, during an audition for Meryl Streep, he said crassly in Italian that he thought she was not attractive enough to play Kong’s leading lady, without realizing that Streep could understand Italian. Despite the cynical nature of her casting, it’s fortunate for the film that the role was given to someone as naturally talented as Lange. The character of Dwan as written could easily have turned out to be a two-dimensional airhead. Lange delivers a genuinely great performance that brings a sense of depth to the character, giving the impression that her sweetness is an unlikely source of strength.

The budding relationship between Dwan and Jack is certainly one of the highlights of the film. Many moments between them exude a certain sort of sexuality rarely seen in blockbuster films today. It may help that much of the film is shot on a pretty relaxing-looking Hawaiian island, and has a hazy Playboy magazine photo spread sort of beauty to it. However, while the film may look much like a vacation on screen, apparently shooting it was anything but. In addition to the stress of a rushed schedule, apparently John Guillermin had developed a reputation for yelling at and demeaning members of the cast and crew. Eventually, it got so out of hand that De Laurentis had to fly out to threaten to fire Guillermin if he continued his behaviour.

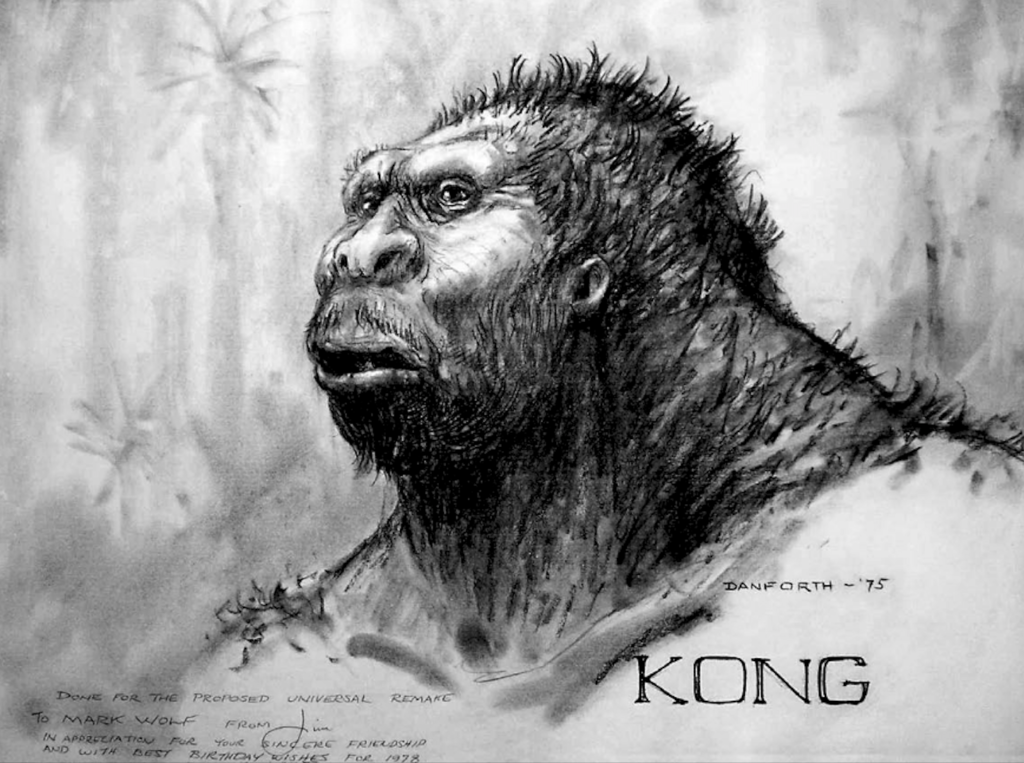

Kong would once again be realized as a monstrous, not-quite-Gorilla, though interestingly, that almost wasn’t the case. Now legendary makeup artist Rick Baker, who was still in his twenties when he was hired to create a Kong suit for De Laurentiis’ King Kong, was shocked to see concept art in which King Kong didn’t resemble a gorilla at all. In what would have been a truly radical direction for the character to have gone in, he was envisioned more like an enormous hominin; a sort of giant cartoon rendition of a Neanderthal. Actually, with a bit of digging, it seems that this unique concept art was created for the Universal Kong remake by stop-motion animator Jim Danforth. Apparently Dino De Laurentiis tried to recruit Danforth to his version instead, but Danforth was less than impressed with the script and so refused the offer, though I suppose this is how the concept art would have been passed around for Baker to see. There was enough insistence from the creative people involved, many of whom had been inspired by the original King Kong, that Kong must be a gorilla, and so Danforth’s missing-link Kong design would be left as a bizarre what-if for the giant terror ape.

Like in the Toho films, stop motion animation was ruled out, so King Kong would again be mostly realized using a performer in a suit. In this case, Rick Baker himself wore it for nearly all of Kong’s scenes. One benefit this suit would have over the Toho King Kong is a much more articulated and expressive face, perhaps even a little too expressive. Honestly, some moments of Kong’s leering or grinning come across as more than a little uncanny. Baker had an affinity for apes, and dreamed of creating “the perfect gorilla suit,” something that would be indistinguishable from a real gorilla. However, with the film’s creative restrictions, limited resources, and rushed schedule, Baker would be disappointed with the end result of his work. He would leave the film fearing that he would never have another opportunity to fulfill his dream creative project.*3

It’s fortunate that Baker’s suit had turned out as well as it did though, because at one point De Laurentiis had hoped to use an unbelievably ambitious full-size animatronic King Kong (about twice as tall as Kong had appeared in the original film) for most of Kong’s scenes. Perhaps he was inspired by the mechanical shark in Jaws, and unaware of its propensity to break down. Special effects mastermind Carlo Rambaldi (who would eventually become best known for his work on Alien and Steven Spielberg’s 1982 film E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial) was brought in to build this giant mechanical Kong. While Rambaldi was widely regarded as a genius, this seemed to be an instance of bitting off more than could be chew. The full-size animatronic Kong took up a sizeable chunk of the film’s budget, and ultimately had extremely limited mobility, was prone to breaking down, and looked hopelessly unconvincing. Ultimately it was only used for a handful of less-than-convincing-looking seconds in the final film. I’ve heard it said though, that the mere creation of the life-size Kong did at least provide the film with some good publicity.

There was also the enormous Kong hands, which Lange would spend much of her screen time interacting with. The hands were metal covered in rubber and horse hair, and controlled through hydraulics by six operators. They were often required to perform delicate tasks like gently caressing or undressing Lange. This required a degree of tenderness that the weighty mechanical hands were not really suited to, which left Lange with a number of injuries, including a pinched nerve in her neck.

In terms of characterization, Kong Kong is particularly sexually charged in this interpretation. The more curious and longing Kong of the original has been replaced by a Kong that’s more overtly lustful. This approach could have come across as entirely vulgar, but it does present Kong as an interesting foil to Dwan, and really some of the best moments in the film are when she’s able to talk Kong down through the sheer force of her personality.

Even with the engaging love story element, the film can feel surprisingly insubstantial for long stretches. I mean mostly figuratively, but also in a literal sense this King Kong can feel strangely empty. While the island of the original film was brimming with depth, detail, and prehistoric life, this version feels like it exists largely in a misty void, with the only other creature for Kong to vanquish being a giant constrictor snake. I think largely because of that, this version just can’t capture the imagination in the way that the original film did.

The pacing of the film may also contribute to the sense of emptiness. There are moments when it achieves a sort of wistful dreaminess, but for the most part the film is aggressively languid. Perhaps the strongest example of this comes in the film’s third act when, during Kong’s rampage through New York, Jack and Dwan take an un-rushed scene to go and have drinks and talk. It makes for a very different experience than the steady stream of thrills and excitement of the original film.

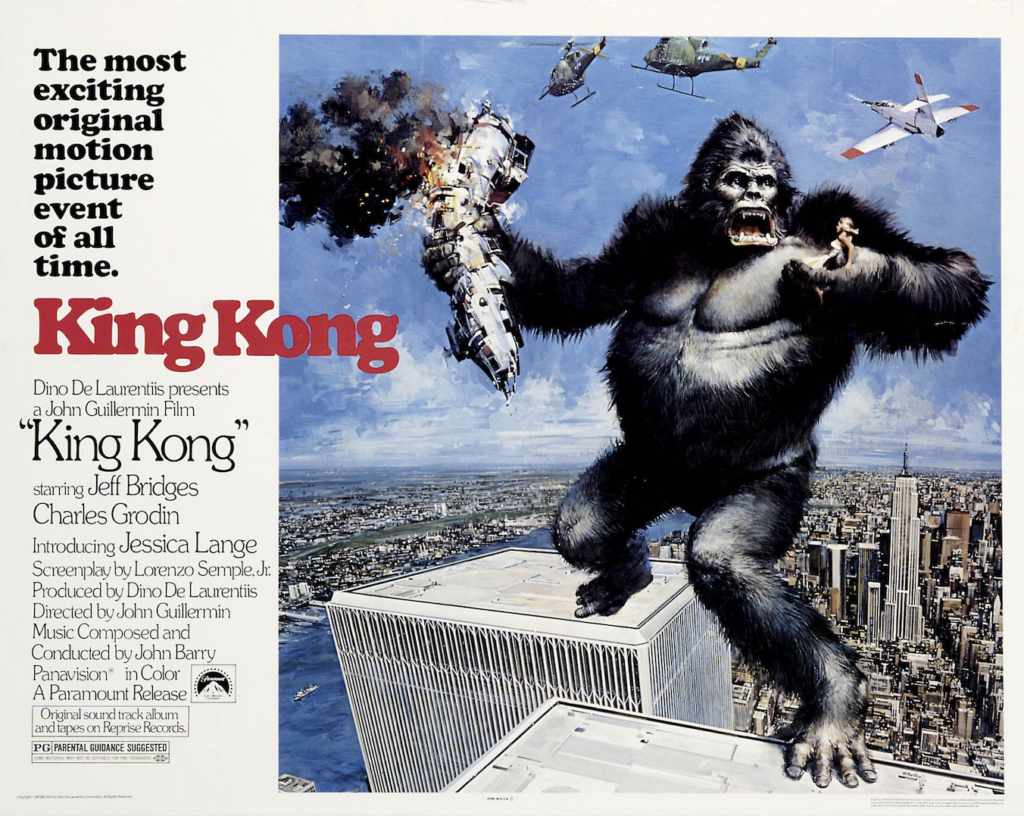

Its dreamy pace notwithstanding, the film does eventually build to an incredibly bloody finale atop the World Trade Center. Soldiers with flamethrowers force Kong to leap from one tower to the other, and there’s a wonderful moment when Jack cheers for Kong as the mighty ape manages to blow up the soldiers. Then helicopters armed with gatling guns are sent in, replacing the biplanes armed with machine guns of the original. Kong sets Dwan down, even though she pleads with him not to, hoping her presence will keep Kong from being shot. It’s as if Kong understands and is ready to accept his fate this time. Kong is of course no match for the helicopter, and ends up riddled with bullets. It’s quite a shocking sequence. With eyes that seem to be welling up with tears, looking at Dwan, Kong plummets to his death.

The film ultimately places the blood of Kong’s death, on Dwan’s hands, like an allegory for the cost of fame, as a crowd of spectators surround her and the corpse of Kong. Apparently the film was originally meant to end with Jack turning away from Dwan, rejecting her in the film’s final moments, implicitly blaming her for Kong’s death, though this was deemed to be a bit too downbeat even for a 1970s remake of King Kong, and so it ends with him staring at her, all alone in a crowd.

The 1976 King Kong makes for a frustrating experience, though I will say it’s not without its virtues. In addition to what was already mentioned, I particularly like how mature and moody it is. In that way, it feels fresh after the colourful and child-friendly Toho take.

De Laurentiis’ King Kong would be a financial success, though a somewhat modest one, partly hampered by its exorbitant budget. Perhaps its greatest impact would be when it was shown on television in a longer (and arguably superior) edit, designed to be shown over two nights. Anecdotally, I’ve come across quite a few vocal fans of this remake who were introduced to it as children, and came across it airing on television. While I don’t agree with them, I can understand why some consider this to be the best version of the King Kong story. Even at its best, I’m not sure there’s anything in the film that I find to be quite as grand and evocative as its stunning poster artwork by science fiction artist John Berkey. His artwork represents King Kong straddling the twin towers of the World Trade Center, like that lost wonder of the ancient world, the Colossus of Rhodes.

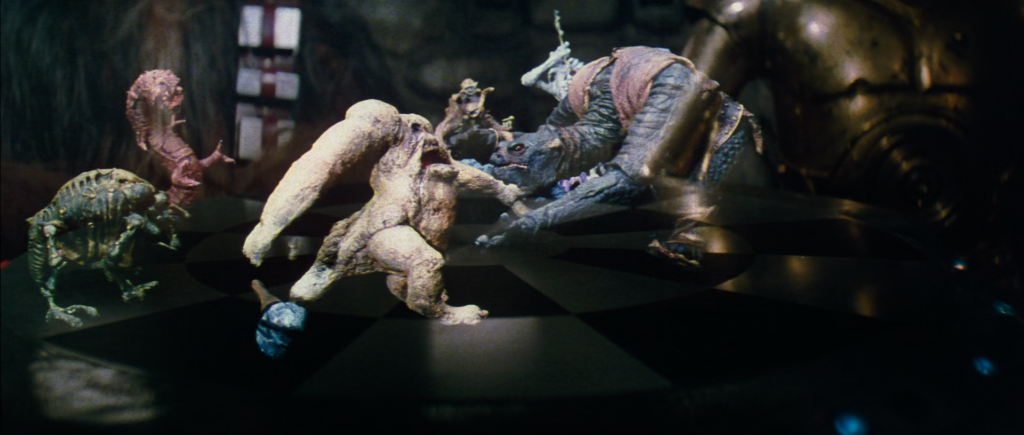

De Laurentiis’ King Kong falls into something of an awkward crevasse in the history of blockbusters, coming after Jaws, which ushered in the new cinematic age, but before George Lucas’ Star Wars (1977), which would really define the age. Much like the original King Kong, Star Wars would prove to be a timeless adventure film with world-building that would inspire generations to become curious about the art of filmmaking. Star Wars also pushed the boundaries of special effects, both in terms of what was possible and what audiences would come to expect. It also still found a welcome place for established special effects techniques like stop motion, with some delightful work by Phil Tippett.

I think it’s worth considering how different De Laurentiis’ King Kong would have been if it hadn’t been rushed into production and had been made a year later. Star Wars would essentially provide the template for many, if not all, of the blockbuster films that would follow. To one extent or another, they would try to imitate its special effects-heavy, fast-paced hero’s journey story. One example would be the 1981 film Clash of the Titans, which would give ancient Greek mythology a Star Wars-like spin. It would feature all sorts of stop motion creations, including a giant monster, The Kraken, which is depicted much like King Kong, towering over a woman dressed in white who’s been offered up to it in sacrifice. For many, Clash of the Titans would be considered the high point both for Ray Harryhausen’s career, if not for the craft of stop motion animation as a whole. It would also be the final film that Ray Harryhausen would create special effects for before retiring, disillusioned with a fast-paced entertainment industry that was largely out of step with his meticulous process.

The craft of stop motion animation would continue to evolve with the next generation of technicians and artists, incorporating new technologies like computer-controlled movements, and motion blur to achieve a more seamless blend with live action elements. This is probably best exemplified in the fantasy horror film Dragonslayer (1981). Industrial Light & Magic, the special effects company founded by George Lucas, was brought in to bring the film’s monstrous dragon, Vermithrax Pejorative, to life. Phil Tippett would say, “The design was so peculiar that it was very difficult to touch, especially the way the wings folded and covered up a lot of the body. As a practical stop-motion puppet, it was a very difficult, hands-on sort of thing. That was one of the first reasons we started thinking we’d have to come up with another way of articulating this thing. And we figured that there must be a way of adapting motion control equipment that was available at this facility to plug into a pretty standard stop-motion puppet.” That variation of stop motion would be dubbed “go motion,” and the end result would be regarded by aficionados as the best cinematic dragon ever. Looking at how alive Vermithrax Pejorative comes across in the film, it feels deeply unfortunate that there was not a King Kong film of this era to once again use stop motion to realize the giant terror ape.

Unlike Son of Kong, which was expediently put together after the original film’s massive success, the more qualified success of the remake meant that the demand for a sequel would be much less urgent. De Laurentiis would struggle to find a concept to justify Kong’s resurrection. There were numerous rejected pitches that may have seen Kong going to Africa or the Soviet Union, or battling a killer whale (perhaps the very same one from the 1977 cult classic Orca). It wouldn’t be until a full decade after the release of the King Kong remake that a concept deemed suitable would be found. John Guillermin would once again direct, and King Kong Lives would make its way to theatre screens in 1986.

It turns out that Kong did not die at the end of the previous film. Being riddled with bullets and falling from the top of a World Trade Center tower has merely put him into a coma. Kong has spent the last decade on life support, and if anything in the film holds any genuine symbolic value, it would be that.

A doctor named Amy Franklin, played by Linda Hamilton who had recently had a breakout hit with James Cameron’s The Terminator (1984), determines that Kong will need to have his heart replaced with an artificial one if he is to live. To necessitate this, Kong will require a blood transfusion from one of his own species. Coincidentally, a female Kong is soon captured in Borneo and the two hit it off.

Soon the two Kongs break loose and promptly get it on. The military intervenes, led by the villainous Lieutenant Colonel Nevitt, who is played with admirable gusto by John Ashton and is one of the genuine highlights of the film. They recapture the female Kong, leaving the King for dead. Of course, King Kong survives and returns with a vengeance to rescue his mate in a gory climax. Kong manages to put a satisfying end to Nevitt by squashing him, but is mortally wounded in the process.

King Kong lives just long enough to see his mate give brith to a new son of Kong. The surviving Kongs are given sanctuary back in Borneo, and I suppose you can call it a happy ending.

King Kong Lives would flop hard. So hard that it was even taken as a factor in Toho stalling a follow-up to the moderately successful return of Godilla to the screen in 1984 with The Return of Godzilla (aka Godzilla 1985). Perhaps more notable than its lack of financial success, the film somehow seems to me to be in bad taste. I’ve occasionally seen King Kong Lives described as “so bad, it’s good,” but it’s so insincere that I’m not sure it can even be enjoyed as camp entertainment. It’s tawdry and cynical. The Toho Kong films may have been similarly outlandish, but with much lower budgets there was a genuine creativity, charm, and passion to them that is absent in King Kong Lives.

The hokey story aside, it’s also embarrassing to see a movie monster who had once been associated with the avant-garde of cinematic special effects, now realized in a way that lags behind relative to the time it was released. Kong himself doesn’t look much better than the man-in-a-suit ape films of the 1920s that Merian C. Cooper had pushed back against. It’s hard not to regard King Kong Lives as a low point in the big screen career of one of cinema’s most iconic characters, though if there’s one thing Kong is known to be good at, it’s eventually breaking out of the shackles of indignity.

Not to force too much of a conceptual parallel, but it may also be worth pointing out that this period of time represented not only a low for King Kong, but also a low for gorillas as a species. A 1981 census had the mountain gorilla population drop to a shockingly meagre 250, devastated by poaching. Primatologist Dian Fossey, who had been studying mountain gorillas on site in central Africa for twenty years, yielding many new insights into their behaviour, saw first hand how close to extinction the great apes were. She adopted an uncompromising conservationist stance, tirelessly using methods that would be regarded with controversy to oppose both poachers and the people who financed them or turned a blind eye to their illegality. It’s very likely that without her, mountain gorillas would have gone extinct in the wild by now. In the process, she made a great deal of enemies for herself, which very likely led to her murder in 1985, a tragedy that remains wrapped in ambiguity and inconclusiveness.

Dian Fossey’s life, work, and death would be the subject of the 1988 film Gorillas in the Mist, which was directed by Michael Apted, and starred Sigourney Weaver (who broke out while sharing the screen with a giant terrifying monster in Alien) as Fossey. Gorillas in the Mist would also give Rick Baker the opportunity to finally create his perfect gorilla suit. The film boldly and convincingly intercuts footage of Baker’s costume with actual footage of gorillas. Not to kick a cinematic icon while he’s down, but seeing Baker’s masterful work in such a sensitively-realized film really just drives home how tired and out of step King Kong was looking and feeling in the 1980s.

As the decade came to a close, stop motion’s use as a special effect for live action films would become increasingly niche. Due to the limited demand from large productions, some artists would have to change careers, like Jim Danforth who set aside his model-making and animation skills to instead focus on his matte painting skills for the second half of his career. There was also a rapidly emerging special effects craft that seemed poised to supplant stop motion and many other techniques. In 1988, James Cameron set out to create an ambitious underwater science fiction film that would become The Abyss (1989). The film posed several unique challenges, including the creation of a living tentacle of water. Cameron had initially approached Phil Tippett to create this effect through the use of go motion, but when it proved to be unfeasible for stop motion animation, Tippett would refer him to Dennis Muren who had started the computer graphics division of Industrial Light & Magic. Computer generated images would be animated to achieve the effect in Cameron’s film. While CGI effects had been used in previous films, The Abyss would open the door to a whole new world of cinematic possibilities, including new possibilities for King Kong.

To Be Continued in Part 3…

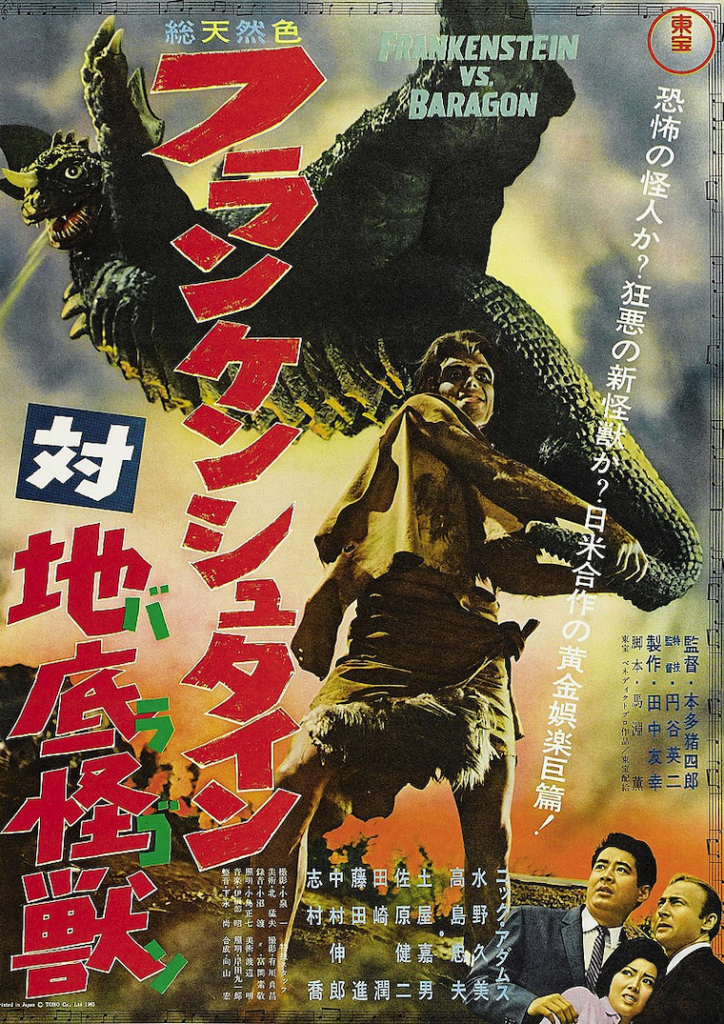

*1 – Even though Frankenstein’s monster would be excised from what would become King Kong vs. Godzilla, Ishiro Honda would make a Frankenstein kaiju film in 1965 with Frankenstein Conquers the World (aka Frankenstein vs. Subterranean Monster Baragon). It’s one of the more overlooked giant monster movies of the era, perhaps because of the lack of a suit for Frankenstein’s monster, or perhaps simply because it doesn’t have Godzilla in it. However, the opponent monster Baragon would appear in later Godzilla films, so there is some connective tissue to the popular franchise. It would also receive a sort-of-sequel with the very entertaining The War of the Gargantuas (1966). I would certainly love to see a “Godzilla vs. Frankenstein” film some day.

*2 – All-white eyes would be a deliberate feature of Godzilla’s design in Godzilla, Mothra and King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack (2001). In it Godzilla is resurrected by supernatural means and takes on a more villainous persona. Apparently, while developing the film, director Shusuke Kaneko watched King Kong vs. Godzilla repeatedly as his main reference for the film’s tone, so I would guess that’s where the detail of the white eyes came from. The film would also include in its cast, Hideyo Amamoto who played Dr. Who in King Kong Escapes.

*3 – Of course Rick Baker would have numerous other attempts at creating gorilla costumes, and it would more or less become his signature. While this will be touched on later in this article, I can’t help but mention one of the most fun examples: the realistic gorilla costume he created for Trading Places (1983). It’s presented as a real gorilla, and used to contrast a character in an obviously fake gorilla suit. In that way, it feels like a bit of a jab at the gap in quality between Baker’s potential and the sorts of gorilla suits all-too-often used in movies.