Kong Jubilee: A 90th Anniversary Celebration – Part 3.

The Absence of Kong.

The 1990s seemed like the perfect time for Kong to have a spectacular comeback. The stage was practically set. There was a wave of renewed interest in the pulpy and fantastical stories of the era that King Kong emerged from, kicked off by the box office success of Batman (1989), a film about another character who first appeared in the 1930s, and which climaxes with its villain, the Joker, taking a white-clad leading lady to the top of a tall building, and ultimately falling to his death, echoing King Kong.*1 It would have been easy to imagine a new King Kong film that harkened back to the adventure stories of the 1930s slotted somewhere in between the likes of The Rocketeer (1991) and The Phantom (1996).

The ‘90s also saw the rise of the new special effects discipline of digital effects. The onset of computer generated special effects opened up a whole new world of possibilities, stunningly exemplified in the groundbreaking photorealistic work seen in the dinosaurs of Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park (1993). The Abyss (1989) may have opened the door for computer animation, but Jurassic Park was the real turning point, one which there would be no coming back from. Like The Abyss, the filmmakers of Jurassic Park had initially approached Phil Tippet to realize the film’s creatures through Go-Motion, and there was some pretty impressive test footage created for it. Eventually the filmmakers opted to take a chance with computer generated imagery instead, in hopes of achieving something even more convincing. Phil Tippett and his team still contributed to the film by using stop motion armatures equipped with motion tracking technology that could translate stop motion movements into a digital model, in order to create more refined and believable creature movements. That particular methodology could be taken to reflect a hope that computer generated creature effects could be an extension of the skills of traditional stop motion animation, though computer generated imagery would ultimately prove to be more of a displacement of those skills. Regardless, it wouldn’t have been a stretch for the same techniques that brought dinosaurs to life in spectacular fashion, to do the same for Kong at that time.

There was also an attempt to make a gorilla-centric film to capitalize on the success of Jurassic Park, in the form of Congo (1995), with was also based on a Michael Crichton novel and produced by Kathleen Kennedy, though even with a number of other very talented people involved, the end result may be described as less than spectacular.

Despite the trends of the ‘90s, King Kong remained conspicuously absent throughout the decade. His only real movie appearances would be in an atrocious, direct-to-VHS animated musical titled, The Mighty Kong (1998), made by Warner Bros. Home Entertainment to cash in on the popularity of Disney’s animated musicals of the ‘90s. Also, perhaps a little more impressively, there was another King Kong car commercial. This time for Audi.

As someone who lived through that time, I can recall that Kong never seemed very removed from the pop culture landscape, often being referenced or homaged, or even used in a theme park ride. The “King Homer” segment in The Simpsons episode, “Treehouse of Horror III” (1992), which parodies the then nearly sixty year-old original film, definitely comes to mind when I think of my own first associations with King Kong as a child. So, despite his absence, Kong had not been forgotten. It should be understood that the lack of Kong in the ‘90s wasn’t due to lack of trying. In fact there would be multiple attempts to resurrect the character. One of the more imaginative efforts would come from Toho.

Toho had successfully revitalized their Godzilla franchise for a new generation. They were films that had Godzilla pitted against new foes, but also some familiar ones as in Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah (1991), Godzilla vs. Mothra (1992), and Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla II (1993). It was during that time that Toho flirted with re-obtaining the rights to the character of Kong Kong, perhaps this time resurrecting him as a cyborg to once again face off against Godzilla in a proper, long-delayed sequel to King Kong vs. Godzilla. When the rights proved to be prohibitively expensive, Toho considered skirting around that roadblock by instead brining back Kong’s robot nemesis, Mechani-Kong. The proposed film would have revolved around Godzilla going into a state of nuclear meltdown (an idea eventually utilized to great emotional effect in 1995’s Godzilla vs. Destoroyah), with Mechani-Kong being used to inject people inside of Godzilla in an homage to Fantastic Voyage (1966). It would have been titled, “Godzilla vs. Mechani-Kong: Micro-Universe in Godzilla.” However, with the character of Mechani-Kong existing in a grey area of legal rights (in fact it seems to be owned by Rankin/Bass), this film would also be scrapped. It’s a shame that neither film was made. It would have been worth it to see the spectacular artist Noriyoshi Ohrai’s poster artwork alone, for a “King Kong vs. Godzilla II” or a “Godzilla vs. Mechani-Kong,” as he had done for the other Godzilla films of the era.

The attempt that would come closest in bringing King Kong back to the big screen in the 90s would come from a New Zealand filmmaker, Peter Jackson. Jackson had made a name for himself directing a string of funny and violent, low-budget films; Bad Taste (1987), Meet the Feebles (1989) and Braindead (1992), before going on to prove himself as one of the most interesting and promising filmmakers of his generation, with his haunting drama Heavenly Creatures (1994). Heavenly Creatures was written by him and his long-time partner Fran Walsh, and starring Melanie Lynskey and Kate Winslet. The film also made an impressive use of digital effects for an independent film. They were realized by Weta Digital, a digital effects company that was newly founded by Peter Jackson, Richard Taylor, and Jamie Selkirk, and based in New Zealand. Jackson would say at the time, “Computer effects are something I never thought I’d be interested in until recently. It’s becoming very clear now that this is what the future of film is going to be… is going to be digital, one way or another.”

Heavenly Creatures would open the door for Jackson to direct his first Hollywood studio film, though Jackson managed to keep production within New Zealand. It would be the CGI-heavy Michael J. Fox horror-comedy, The Frighteners (1996), made for Universal Pictures. Upon being impressed by how well The Frighteners was coming together, Universal approached Jackson to direct a monster movie remake that they had been trying to get off the ground for some years at that point… a remake of Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954). Jackson was not particularly interested in that film, but in conversation it came up that Universal also still hoped to remake a film that had been a major source of inspiration for Creature from the Black Lagoon, with that of course being King Kong. As it so happened, the original King Kong was Jackson’s favourite film.

“Biggest fan,” is a term that’s often thrown around, but there’s a strong case to be made that Peter Jackson really is the biggest fan of the original King Kong. It was the film that inspired him to become a filmmaker, with one of his earliest shorts being an attempt to re-recreate the film in stop motion. He would say, “… everything changed after I saw Kong. For starters it gave me a real sense of what I wanted to do as a career, which wasn’t actually to become a director. It was to become a special effects person, because what King Kong does I think, if you’re in the right frame of mind, is it totally inspires you to think about the trickery of films. It’s the wonderful escapist use of special effects.” Jackson would go on to own a number of props and puppets from the original film, and have peripheral creative projects related to it, like taking time with his Weta special effects team to study and replicate the exact techniques used by Willis O’Brien that had not been thoroughly documented, for the purpose of posterity in addition to their own education. Whenever Jackson speaks about the original King Kong, it’s clearly coming from a place of deep love and knowledge.

In fact, it would be Jackson who would make Universal aware then that they did not actually hold the rights to remake the original film, but rather the rights to use the characters and adapt the novelization of King Kong, a subtle but legally important distinction. After struggling and failing to push it through pre-production limbo for the previous two decades with directors like John Landis coming-and-going, with Jackson’s passion for the original, skill as a director, and familiarity with digital effects, Universal had finally found the right filmmaker to realize their own iteration of King Kong.

Jackson and Walsh set about writing their own version of the screenplay. Their approach to the material was that it should be a fast-paced work of globetrotting high-adventure and fantasy, with a good dose of light comedy, not unlike an Indiana Jones film. It’s reflected in the tone of the screenplay itself, which includes cheeky descriptions like “KONG rampages after [the natives], STOMPING ON THEM and BITING THEIR HEADS OFF … in a scene that not only gets a PG-13, but is PRAISED by the MPAA for its sensitivity!” It was to be full of exciting moments like an aerial baseball game played between biplanes, or Kong throwing a statue of himself like a spear to impale someone. While the story was set in the 1930s, Jackson and Walsh did make many interesting deviations from the original film. Jack Driscoll would be a former WWI fighter pilot, who in the finale would have taken to the skies to shoot down other planes in an attempt to save Kong. Carl Denham would have been more unambiguously villainous, using cruelty to try to train Kong for his broadway show, and ultimately being trampled to death by Kong after breaking free. Ann Darrow perhaps had the biggest change, going from an out-of-work American actress to an English archeologist woman of action, not unlike the popular heroin Laura Croft who had then recently made her first appearance in the video game, Tomb Raider (1996). Supposedly Kate Winslet, George Clooney, and Robert De Niro were being courted to play these versions of Ann, Jack, and Carl.

The pre-production period for this 90s version of King Kong yielded work that seemed to promise a truly impressive blockbuster for the era. Weta Workshop (the Weta company that focused on props and practical effects) filled their studio with dinosaur maquettes and began work on a new giant mechanical Kong hand. The Weta Digital team entered a six month period of research on how to best develop and implement the special effects to realize the complex project.

The intention was to film on location in New Zealand in 1997, for an intended Summer of 1998 release date. However, Universal soon got cold feet on the project. It may have had something to do with the very entertaining The Frighteners underperforming financially after it was poorly marketed and pitted against the juggernaut Independence Day (1996) at the Summer box office, rather than released on a date closer to Halloween as Jackson had pushed for. It may have also had something to do with King Kong having a planned release in a year which began to look over-crowded for its particular niche, with both an American Godzilla remake and a Disney remake of Mighty Joe Young set to open then. Not wanting to directly compete with such ostensibly similar films, Universal cancelled Jackson’s King Kong despite the months work that had already gone into it.

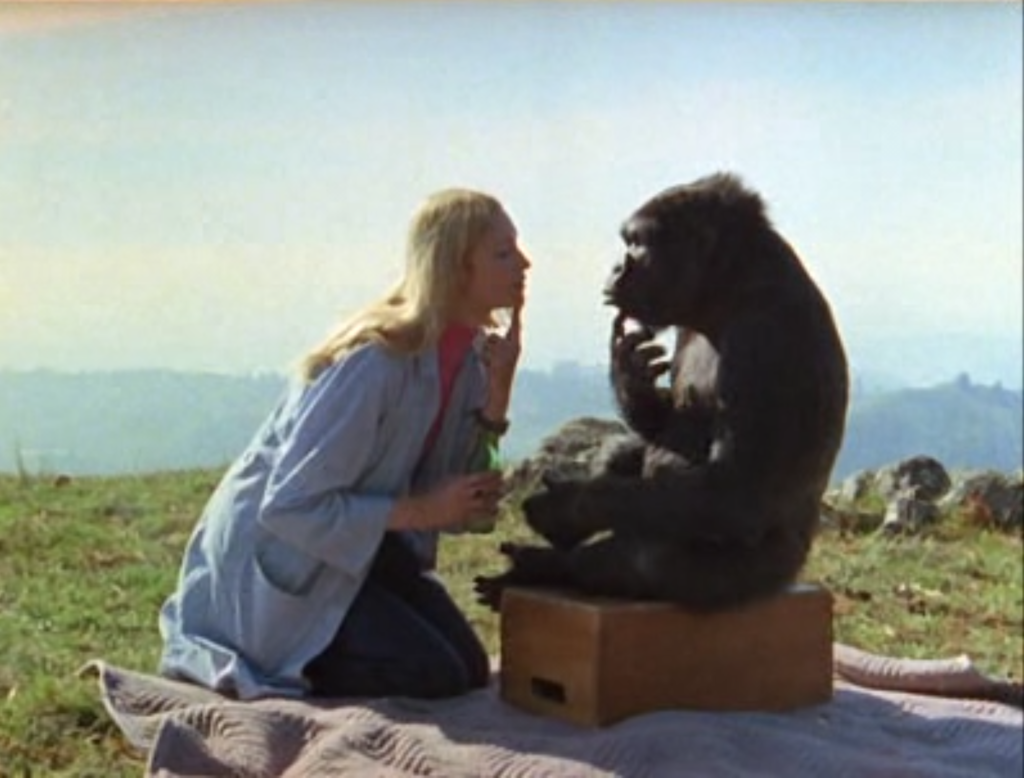

The remake of Mighty Joe Young would end up being a film that is schmaltzy even by the standards of 90s Disney films, though it’s not without its redeeming traits, including some outstanding special effects work by Rick Baker. It also makes some reasonable tweaks to update the story, like for instance changing Jill Young (played by an up-and-coming Charlize Theron) from the daughter of a colonial-type farmer, to instead be the daughter of a Dian Fossey-inspired primatologist who is murdered by poachers in the film’s prologue. However I think the remake does lose a lot of the thoughtfulness of the original film, replacing the self-critical themes dealing with show business and using animals for entertainment, with a much more 90s Disney-safe generic anti-poaching message. Despite being a moderately charming film, the Mighty Joe Young remake would outright bomb at the box office.

Perhaps the box office reaction to the Mighty Joe Young remake could have been predicted, as just a year prior, the film Buddy (1997), which could be described as being based on a real life Mighty Joe Young story, also failed at the box office. Written and directed by Caroline Thompson, Buddy stars Rene Russo as historical figure Gertrude Lintz, an eccentric New York socialite who devoted herself to adopting sick or orphaned animals, including great apes. In the 1930s she cared for two gorillas whom she attempted to raise and treat in a method more fitting for human children, dressing them in clothing, having them do chores, and teaching them table manners. As the gorillas grew older they became untenable as pets and so one would be donated to the Philadelphia Zoo in 1935 (and become one of the longest-lived gorillas in captivity), and the other would be sold to the Ringling brothers’ circus in 1937, renamed “Gargantua,” and eventually inspire Terror on the Midway, the classic 1942 Fleischer brothers’ animated Superman short. Buddy takes some historical liberties, like compositing the two gorillas’ lives into one. I think it’s ultimately a more artistically successful film than the Mighty Joe Young remake, even if its attempt to grapple with the ethics of Lintz’ desire to anthropomorphize and domesticate animals that are very close to humans but nonetheless wild animals, yields a tone that often clashes with what is ostensibly meant to be a family friendly movie. At any rate, it seems that yet again audiences weren’t so very interested in seeing a friendly gorilla who lives at the end.

As for the 1998 American remake of Godzilla by Independence Day director Roland Emmerich, which sees the giant monster rampage through New York… even as a child completely enamoured with the character of Godzilla, I’d leave the theatre with a rare feeling of disappointment. Not only was the film devoid of the subtext that typically makes Godzilla feel substantial as a character, but it also lacked the awe that so easily captivates audiences of all ages, leaving only a husk with Godzilla’s name attached to it. Shogo Tomiyama, the producer behind the Godzilla films from 1989 to 2004, and eventual president of Toho, would perhaps say it best, quipping that, “they took the God out of Godzilla.” This version of Godzilla would be memorably slighted in the 2004 film Godzilla: Final Wars in which the Japanese suitmation version of Godzilla obliterates the computer generated American-designed Godzilla (or maybe just Zilla) in an arguably petty, but undeniably satisfying thirty second sequence. I should say though, that in recent years, I’ve heard numerous people defend the film, making the case that it’s far more palatable if treated as an unofficial remake of The Beast from 20, 000 Fathoms, rather than Godzilla.

Before moving on from the ‘90s, it may be worth mentioning that it has been speculated that some of the creative work done on Jackson’s ‘90s attempt on King Kong may have been lifted by Universal for yet another remake, the 1999 digital effects-heavy version of The Mummy, directed by Stephen Sommers, and starring Brendan Fraser, Rachel Weisz, and Arnold Vosloo. Whether or not certain elements were drawn directly from it, people who worked on Jackson’s ‘90s attempt at King Kong would notice numerous similarities, and watching the very entertaining The Mummy might give some sense of what flavour that ‘90s version of King Kong might have had.

With King Kong cancelled, Jackson would instead move on to an ambitious adaptation of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of The Rings, a massive undertaking that would would keep him occupied for the next several years. The trilogy of films yielded would achieve massive financial success and become some of the most beloved movies released in my lifetime. In addition to being an impressive achievement in artistry, the films would also be a landmark in the progression of digital effects, with the most famous example being the realization of the devious creature, Gollum. Actor Andy Serkis provided the voice for the character, as well as his movements and physical interactions with other characters. This was through the method of “motion capture,” in which markers are used to give animators reference data, much like the armatures used for the motion in Jurassic Park, only with the spontaneity and authenticity of a human performer. If 1933’s King Kong might be said to be the first special effect character to have a soul, then perhaps something similar could be said for Gollum, as an entirely computer generated character, who believably emotes in a human way and seamlessly interacts with live action characters.

King Kong III.

There was some discussion of Jackson taking a year off after the completion of the final Lord of the Rings film, The Return of the King in 2003. A rest after such a monumental undertaking would have been more than understandable, but perhaps not wanting to lose any momentum, Jackson instead jumped right into developing his next film project. The wild success of The Lord of the Rings trilogy gave Jackson the clout to make just about whatever he wanted as a follow-up, and what he wanted to make was King Kong. Jackson would say, “… for me it was always unfinished business. It was a dream that I had wanted since I was a kid that had been unfulfilled in a way that wasn’t particularly pleasant back in 1996, and I always feel a little pang of disappointment that that was the film that I wish could have made that I never did get made.”

Jackson’s version of King Kong had changed since the ‘90s though. It may be appropriate that a major theme of The Lord of The Rings is that our experiences change who we are, and that in some ways, after a great undertaking, you can never really go home again, because it seems that the experience of making the trilogy had changed Jackson as a filmmaker. Rather than a tightly-paced adventure film, Jackson would now realize King Kong as a sprawling epic that would more closely adhere to the characters and narrative structure of the original film than what was intended with the ‘90s remake. Jackson would write the screenplay for this new version again in collaboration with Fran Walsh, and also Philippa Boyens who had co-written and co-produced The Lord of the Rings films. Compared to The Lord of The Rings, which had a pre-production period of about three and a half years to plan shots, build props, and generally work out all the important details, Kong would come together much more quickly. Boyens would say, “We were all exhausted. We were all pretty tired coming out of Lord of the Rings and then we went straight into this.” King Kong would be released less than two years after The Return of the King debuted.

Naomi Watts was cast as Ann Darrow who, in this version, is given a bit more of a backstory, being specifically a Vaudeville performer who is desperate after being recently laid-off due to the great depression. One of my favourite scenes has Ann specifically use her performance skills to charm Kong, before asserting herself and telling the giant ape “no” when he gets too much of a kick from pushing her down and laughing. Watts brings a wonderful wide-eyed earnestness to the role, and a combination of sweetness and strength that isn’t entirely unlike Jessica Lange’s. I think though that Watts benefits from a less naive and more thoughtfully written version of Kong’s leading lady, and I think the film benefits from an actress who is comparably talented but much less raw, as at that point Watts had already had several years of acting experience and had worked with directors like David Lynch and Gore Verbinski. Watts even received the symbolic approval from ninety-six year-old Fay Wray. After a bit of hazing the new girl, the original actress would tell Watts that, “Ann Darrow is in very safe hands, my dear.” This was while Jackson was courting Wray for a cameo in the film’s final scene, one which Wray would pass away before being able to film.

Jack Black was cast as Carl Denham, who has been given a little bit of a young Orson Welles makeover, and a cheeky and sleazy characterization. The defining quality of this version of Denham is that he is someone who is willing to cross ethical boundaries in order to complete his film, including willingly letting harm befall his crew in order to capture some of the last genuine mystery left in this world. I should say that I like Jack Black very much, though in this case I think it could be said that he gives an excellent performance for a different, much zippier film than the one he’s in. Black himself would put a spotlight on this incongruity, jokingly describing struggling with being a “habitual over-actor” in a behind the scenes video, though again I do think he’s giving a very good, heightened performance. He’s also joined by his Orange County (2002) co-star Colin Hanks, who plays Preston, an assistant to Denham, and functions as both a comedic foil, and also later a dramatic foil once Denham is faced with some consequences for his decisions.

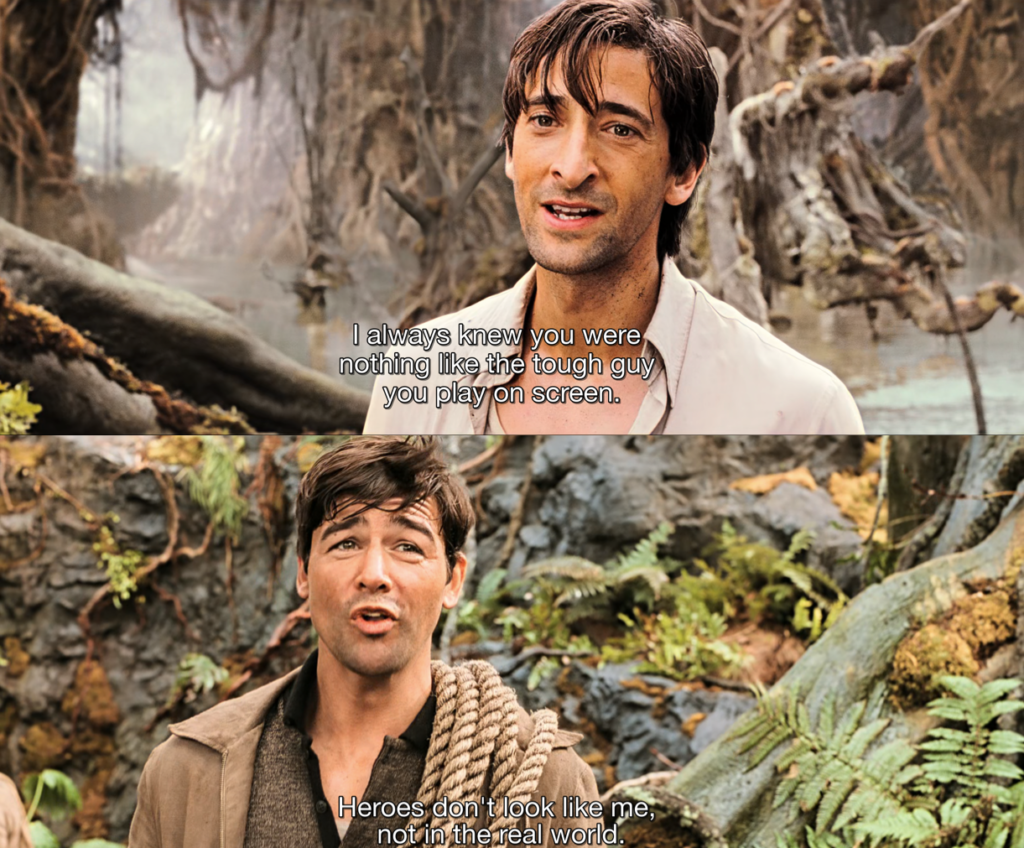

Adrien Brody plays Jack Driscoll, who sees the most change from the original film’s version of the character. He is now a bookish playwright-turned-screenwriter for Carl Denham’s film, and who is initially disinterested in an Ann Darrow eager to impress him, before falling for her during their voyage. The suggestion for this change came from Fran Walsh who felt that as Kong might represent an ultimate alpha male, it wouldn’t make sense to have a male lead who would compete for Ann’s affections on that level, but instead present a more sapiosexual appeal. There’s also the peculiarity of the Jack Driscoll character of the original film having essentially been split into three separate characters. One of the other two is the paternalistic first mate Hayes who is played by Evan Parke who spends most of his screen time mentoring a young and eager crewman named Jimmy and who is played by Jamie Bell. The third is a self-absorbed, hammy matinee star, Bruce Baxter, played by Kyle Chandler.*2 He gets some of the sexist lines that Jack Driscoll had in the original film, but now comedically repurposed for the movie-within-the-movie. It’s probably obvious reading this, but having one character turned into three is also exactly the sort of thing that quickly adds up to a much less economical narrative than the original.

In addition to a live action role in the film, playing the part of the ship’s cook, Lumpy (a character who originated in the 1932 novelization), Andy Serkis would play King Kong. Much as he did for Gollum in The Lord of the Rings films, Serkis would provide the the motion and face capture references (together usually just called “performance capture”) as well as giving the base audio tracks that could be altered in post production. He would even dress up in a gorilla costume, with arm extenders and false teeth, so as to give the other actors in the film something to play off of. It may appear unnecessary for a computer generated character or even silly at a glance when viewing behind-the-scenes footage, but considering how many computer generated characters in other films of the era feel disconnected from their live action environments largely because actors are forced to perform against the likes of green balls on sticks, then it starts to make sense. I think it all pays off with what I consider to be the strongest on-screen connection between Kong and his leading lady. Serkis’ performance really comes through in the film! That shouldn’t be used to discount the tireless work of computer animators either. Really I think it’s a testament to their artistry and labour, that an actor’s performance could be carried through the animation process of bringing Kong to life.

Unlike Shoichi Hirose who bluffed his ape research for King Kong vs. Godzilla, Serkis would become very studious of gorillas in preparing for the role. He’d initially study gorillas in captivity at London Zoo, but after intuiting that their behaviour must be different from gorillas in the wild, set his sights on traveling to Rwanda. As he couldn’t be insured by the production, he went anyway on his own dime, reflecting a real dedication to the role. Serkis would say, “The most important thing I learned really, from observing gorillas both at London Zoo and in Rwanda was when you talk about ‘studying gorillas’ it’s like saying ‘studying human beings’ because they are as totally different, idiosyncratic as you or I. You’ll have a very moody gorilla, you’ll have a very loving gorilla, you’ll have a very uptight gorilla, you’ll have a very relaxed gorilla, you know? They have personalities exactly like you or I, and why should we think any different?” He would also make some contributions to how King Kong would be characterized in the film, like for instance insisting that Kong should be shown chomping on bamboo rather than people, because gorillas are almost exclusively herbivorous (only getting a bit of protein from insects like ants and termites). The skillset that Serkis developed on Kong would certainly serve him well when he later starred, and he really is the star, in a trilogy of rebooted Planet of The Apes prequel films, using performance capture to play a mutated chimpanzee named Caesar. His attention to detail in his performances as Kong and Caesar would even earn him praise from primatologists. Dr. Tara Stoinski, President and CEO and Chief Scientific Officer for the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund would say of Serkis, “I think that his portrayal of apes is truly amazing. I mean he really captures just the subtleties of how they move and interact.”

While Kong has been returned to more or less the same scale that he appeared in the original 1933 film, his appearance and proportions would be changed drastically. With his quadrupedal posture, distinctly herbivorous belly, and general physical proportions, this is the most Kong has ever resembled an actual Gorilla. There are a few minor design choices that deviate from a typical gorilla, like having a less prominent brow ridge to better see Kong’s eyes, or modifying Kong’s hind legs so he looks more sturdy when standing upright. Just the sort of thing to make Kong work a little better as a cinematic creation. It may be easy to underestimate the creative work in developing the look of what can be called “just a big gorilla,” but the design process for this version of Kong was quite intensive. Details like scars, and a broken jaw make Kong a distinct character rather than a generic ape monster, and also visually communicate that Kong as a character has had a violent history by the time he’s introduced in the film. One of the cinematic influences cited was the 1939 adaptation of The Hunchback of Notre Dame, starring Charles Laughton, and you can see much of the sympathetic Quasimodo in both Kong’s asymmetrical appearance, as well as his relatability as an outsider, pining for the beautiful Ann.

Even though Kong has been updated to more closely resemble a real gorilla, a very different approach was taken for the other monsters of Skull Island. Most notably that the dinosaurs are deliberately depicted as retrograde in their scientific accuracy, with a more monstrous and reptilian appearance rather than the more avian appearance that modern palaeontology infers they actually had. It fits with the notion of the film being a pulpy throwback. The Tyrannosaurus Rex-like dinosaurs are even given three fingers rather than the two that the famous dinosaur actually had, in homage to their inaccurate portrayal in the original film. Perhaps because of that distinction they’re referred to as “V-Rex” in promotional materials. Instead of just one, Kong battles a whole trio of V-rexes to protect Ann in the film’s biggest set piece.

There are also the very memorable creatures in Peter Jackson’s own wonderfully horrifying version of the lost Spider-Pit scene, which include giant weta bugs, giant spiders, and some very unsightly toothed worms, which devour Lumpy in what is the film’s most gruesome moment. For a digital effects heavy film that is now pushing two decades old, visually it’s not as dated as many contemporaneous films have. Admittedly not every effects shot looks convincing, and some seem to reflect the more rushed nature of this production, but there’s a level of care and attention to detail that has allowed the film to hold up remarkably well in most regards.

To the film’s detriment, another aspect that is perhaps intentionally retrograde is the depiction of the people of Skull Island. While the Skull Islanders, have been made more ethnically ambiguous, they are rendered as unapologetically frightening and evil, invoking some of the worst and most odiously dated stereotypes of indigenous groups throughout world history.*3 Really, their depiction is not so different from the monstrous orcs and goblins of The Lord of the Rings films. That isn’t necessarily to say that these depictions are coming from a palce of hate. I think it’s more a sort of thoughtlessness. I’m reminded of the sort of representations you might see in a film like Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom for instance, which can come across as more of a blindspot on the part of the filmmakers that comes with loving movies from the 1930s, and a lack of reflection when translating some of the imagery from them into a modern film. However, I will say that it all comes across as a far less sympathetic depiction than what was seen in the original 1933 film, which as previously discussed, is certainly not faultless, but did try to recognise how the arrival of outsiders had disrupted the delicate balance to their culture that had developed on an island present with Kong and numerous other monsters. For instance, there’s no moment in this remake quite like the one in the original where a child cries during the chaos of people running in fear as an enraged Kong destroys the Skull Islanders’ village. In the original there’s a sense that Merian C. Cooper’s was grappling with his own complicated and ugly thoughts and feelings on colonialism which produced something undeniably messy but also disarmingly sympathetic. Not to say that they shouldn’t have played an adversarial role in the story, but the depiction of the people of Skull Island in this remake just comes across as inconsiderate.

Skull island itself is quite astonishing. It’s stylized, like concept art come to life, making use of miniatures and digital effects compositing to create an environment that does not quite exist on earth. Completely unlike the often empty feeling of the island in the 1976 King Kong remake, this has an abundance of visual detail. It’s a rich, entirely imagined world, though what strikes me as perhaps even more impressive is the recreation of Great Depression era New York City in New Zealand. The rational for that is because modern day New York doesn’t hold much resemblance to the New York of 1933, so it had to be created, and in its own way is no less wondrous than Skull Island.

Of all the King Kong films, this is the one I struggle most to find some degree of objectivity when discussing. As someone who was a young teenager during the lead up to its release, impressed by The Lord of The Rings films and who loved the original King Kong, I find it difficult to put into words the magnitude of hype that I had for Jackson’s King Kong. I had lived through the anticipation of Star Wars prequels and The Matrix sequels, and I think even those may have paled in comparison to my excitement for this new King Kong. It seemed forgone that it would be “my King Kong,” generationally speaking. Something that contributed to that excitement was how open Peter Jackson was about the making of the film, doing something out of the box by releasing video diaries giving rare insight into the production process while it was being made. At the time what came across was Jackson’s infectious enthusiasm for filmmaking and for King Kong, though it’s perhaps more interesting for not trying to hide some of the challenges and intense exhaustion of tackling such a gargantuan film. Looking back at those production diaries and some of the behind-the-scenes materials, I think it’s possible to get insight into some of the film’s deeper faults or idiosyncrasies.

It does seem that at least some of the unevenness in the film is a consequence of the relatively compressed schedule, in contrast to what Jackson and his crew had available with The Lord of The Rings films. Time can be a more important asset in assuring the quality of a film than even money, and pressure tends to bring out certain shortcomings. I should say though that while noticeable, none of these faults in King Kong are nearly as egregious as what’s on display in Peter Jackson’s later The Hobbit trilogy. As challenging as the time restraints on King Kong may have been, the circumstances that lead to Jackson directing The Hobbit films would be far, far worse. Stepping into to replace Guillermo del Toro, he would have only a couple months of pre-production, leaving most of the film unprepared. Unit production manager Brigitte Yorke would say “Peter [Jackson] never got a chance to prep those movies… I can’t say that… but he didn’t.” Richard Taylor, the Weta Workshop creative director would describe the experience of making The Hobbit films as “Laying the tracks directly in front of the train.” Looking at behind-the-scenes footage for The Hobbit movies, and the stress and exhaustion Jackson visibly experiences looks like enough to kill a lesser director. Of course the final films reflect that in their own way. I do wonder if this is a reason why Jackson seems to have stepped away from such monumental productions in recent years, instead favouring documentary filmmaking. Still, I think there are some issues with Jackson’s King Kong that could be more conceptual.

In the production diary for the fourth day of filming King Kong, there’s a moment where Jackson keenly highlights the hat that Naomi Watts is wearing is based on the one that Fay Wray wore in the original film, saying “This is our a tribute to Fay.” Watts then adds, “Little homage… many more to come.” She’s not kidding, the film is absolutely overstuffed with little homages, to the point where someone may reasonably wonder if the film is just one big homage and not much else.

In recent years there have been a lot of discussions as to what extent the artistic direction of big franchise films should be in the hands of people who consider themselves to be fans of those respective franchises. I think Jackson’s King Kong represents an interesting case study in that respect. In a way it is the ultimate fan film. It reveals itself to be both a product of intense devotion and passion for its source material, but it also reveals many of the (spider) pitfalls of that approach. The film can be ferociously indulgent, and often feels as if it’s on the verge of collapsing under the weight of its own reverence for the original film. That’s probably most obviously highlighted in how the original film was a flawlessly-paced hour and forty minutes, this remake is an often stumbling three hours. Every moment from the original is treated as “the moment.” On the flip-side, much that has been added to the story feels extraneous, like for instance the inordinate amount of time spent with the Jimmy character who notably reads Joseph Conrad’s novel Heart of Darkness for the film to hammer an obvious parallel, only for him to disappear by the film’s final act. It can feel like a byproduct of a film that feels lost in how to reinterpret the original film.

While asking “what does it mean?” with the original King Kong yielded some provocative, complex and even contradictory interpretations, one may be tempted to interpret the meaning behind Jackson’s remake as simply, “Peter Jackson loves King Kong.” I’m not sure it is quite as simple as that (I think the film does succeed in expanding on how the original film grappled with the exploitative nature of the entertainment industry), but the film does seem to eagerly invite that take on it.

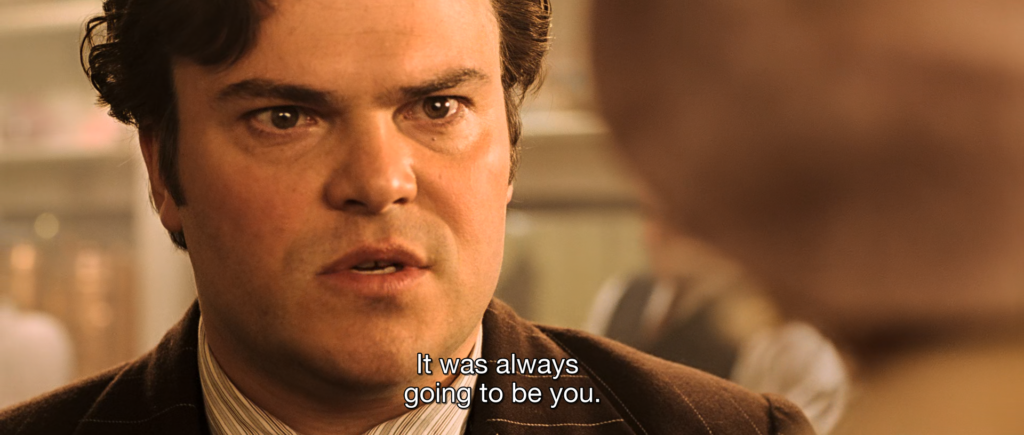

There’s also a strange feeling of inevitability that pervades the film. I suppose that is largely due to it telling a story we’ve seen before, and that we know how it will end. It’s even reflected in the dialogue. For example, when Carl Denham recruits Ann to star in his film he tells her with a mystified expression, “It was always going to be you,” as if it’s all being guided by the hand of fate. It can feel a little like the filmmakers are in a way trapped by the inability to deviate from certain beats of the original film.

I think because of that air of predestination that some of my favourite scenes in the film are the ones that offer a brief respite before the inevitable and tragic finale. That includes one of the most oft-criticized aspects, the film’s clumsy pacing; Kong holding Ann and sliding around on a frozen pond. I’m actually quite fond of it as a moment of pure fairy tale romance. Same goes for the moment of Kong and Ann watch the Sun rise from the top of the Empire State Building, immediately before the inevitable heart-wrenching climax.

It’s hard not to wonder what could have been had Jackson made the film in the ‘90s, or had Jackson and his team taken a year off after The Return of the King to creatively recharge before setting out to make Kong without the pressures of a time crunch. However, despite how harsh I’m sure some of my criticism of it sounds, the film certainly has many virtues. At its high points it’s stirring and achingly beautiful. Even at its low points, I still prefer its over-stuffed excess to the bareness and languidness of the De Laurentiis’ 1976 remake. There’s a majesty to it that has become rare in the modern blockbuster era. The final act in particular I think has some of Jackson’s best filmmaking. I think it also has the best interpretation of the “beauty and the beast” aspect of the King Kong story. Again, I believe a major part of that comes from having Serkis present on set for Naomi Watts to act with, and provide the basis for animators to bring about that on-screen chemistry between Ann and Kong, which goes beyond what any of the previous films had achieved. There’s also a go-for-broke sentimentality that Jackson approaches the relationship with, that I think ultimately does work. In a certain regard it may even be the saving grace of the film.

King Kong would preform pretty well at the box office, not grossing quite so much as the likes of Star Wars and Harry Potter. Perhaps notably though it outperformed that era’s wave of superhero movies including Batman Begins (2005), Superman Returns (2006), X-Men: The Last Stand (2006), and Fantastic Four (2005). It was a time when comic book movies had yet to achieve the box office supremacy that they soon would. When considering what place Peter Jackson’s remake has in Kong’s legacy, I think one thing that can be said with certainty is that it affirms that King Kong is not a B-movie monster. He is undoubtably an A-lister, and it’s satisfying to see the giant terror ape in a film that presents him as such.

Legendary Kong.

There were murmurs that Peter Jackson was perhaps not entirely done with the world of King Kong. Where could King Kong possibly go after Jackson’s ultimate homage? The answer was apparently a prequel, intended to be about a group of soldiers who find themselves on Skull Island during the the first World War. This concept would eventually be waylaid as the blockbuster ecosystem underwent a shift.

Digital effects reached a new pinnacle with James Cameron’s Avatar (2009) which revitalized the 3D film gimmick, and introduced a new wave of stereoscopic filmmaking. It went on to become the highest grossing film ever at the time. It’s a film that I think bares at least some resemblance to Merian C. Cooper and Willis O’Brien’s old War Eagles pitch, with its former military hero who finds redemption among an indigenous society, and in its climax uses large flying creatures to defeat a technologically superior enemy. It’s perhaps just a coincidental similarity, but does highlight that Merian C. Cooper’s vision for blockbuster entertainment retained relevancy in the 21st century.

There were a few blockbuster films that would try to some degree to replicate Avatar. One example would come from Legendary Pictures, a relatively new production company that had a financing and distribution deal with Warner Brothers, which would in 2010 release a remake of Clash of the Titans. It was presented in 3D and even went as far as to cast the same lead actor as Avatar. While it lacked Ray Harryhausen’s animation and the charm of the original film, it would be successful enough to warrant a sequel. Despite not being directly tied to any established franchise or intellectual property, Legendary Pictures would also have a modest success with the 3D release of Guillermo del Toro’s Pacific Rim (2013), an homage to classic tokusatsu films that saw human characters pilot giant robots to fight kaiju (called as such in the film) invading from a portal to another dimension.

Avatar-imitators would not be the type of film that would come to dominate the blockbuster landscape. As I’m sure most people reading this are aware of, what Hollywood would instead end up chasing would be what was created with the “Marvel Cinematic Universe.” While officially beginning with the release of Iron Man (2008), it was the massively successful release of The Avengers in 2012 that would solidify the formula of interconnected films that could be used to tie-in and promote one another, and build audience excitement up towards an event film where characters from various movies come together.

It was during this time that there would be some forward momentum on the Skull Island prequel film. Universal would partner with Legendary Pictures to develop it. Nearing the end of his Hobbit trilogy, Jackson made the decision to not return to direct the Skull Island film himself, but did intend to play some role as a producer. Guillermo del Toro’s name was mentioned as a possible director, though in 2013 Jackson would select an up-and-coming director for the film, Adam Wingard. This decision was made after seeing Wingard’s home invasion horror-comedy-thriller You’re Next (2011). Wingard has since downplayed his own involvement in the film’s development, and expressed that he was not particularly interested in the period setting and had hoped to bring the King Kong story into the present day.

Concurrently Legendary Pictures had also worked out a deal with Toho to be able to create a new Godzilla remake, released in 2014. The end was a result is admittedly on the drab and dull side, leading to a frustrating experience. In many ways it wouldn’t be so different from the previous American Godzilla, largely empty in emotion and subtext, with dreary visuals and a rote plot revolving around trying to stop monster eggs from hatching. It did have incredible sound design though. One big distinction it would have from the ‘90s American Godzilla is that is that Godzilla, bigger than ever and impervious to the weapons of men, would feel appropriately godly. Despite having less than ten minutes of screen time in the entire film, there’s a gravitas and a grace to the film’s depiction of Godzilla. Perhaps the most memorable moment is when Godzilla’s tail sweeps past the camera in eerie silence before Godzilla blasts an updated version of his recognizable roar. The film would also be a considerable success.

Seeing an opportunity to have their own cinematic universe, Legendary Pictures made a deal to move the Skull Island film from Universal to Warner Brothers. In the process they severed ties between this gestating film and Jackson’s remake as well as his creative vision. Dubbing their endeavour the “Monsterverse”, Legendary intended to use as their model what Toho had accomplished beginning in the 1960s with King Kong vs. Godzilla. Wingard would also be lost in the shuffle, though producer Mary Parent would stay with the project during this transition. Kong: Skull Island was set to be released in 2017. It’s perhaps also worth pointing out that during all this, Universal Pictures would instead focus on creating their own cinematic universe by reimagining their roster of classic horror movie monsters. Despite its ambitions, Universal’s “Dark Universe” would not make it beyond a reboot of The Mummy (2017) starring Tom Cruise, Sofia Boutella, and Russell Crowe.

As the release of Kong: Skull Island drew closer, it became difficult to gauge how a new Kong film might be received, and were it could fit into the modern landscape of pop culture.

2016 saw the release of The Legend of Tarzan which revived Edgar Rice Burroughs’ classic pulp hero Tarzan, a character who was raised by apes (called “Mangani” in the books, but generally interpreted as gorillas), and a part of the cultural milieu that the original King Kong would eventually emerge from. Alexander Skarsgard plays a Tarzan who has retired and settled down in British civilization and has married the heroin Jane, played by Margot Robbie, but he is recruited by an American veteran played by Samuel L. Jackson, to return to Africa to expose Belgian King Leopold II’s crimes against humanity in the Congo Free State. The film also includes Christoph Waltz playing a pulpy villain named Leon Rom, who is loosely based on the much worse real-life figure of the same name. Some have even speculated that the historical Rom may have inspired the character of Kurtz in Heart of Darkness. The Legend of Tarzan is a finely crafted blockbuster, admirable in how it uses its pulp material to grapple with real history. In some ways it reminds me of Jackson’s King Kong in its throwback vision of thrills and romance. It also struck me as unmistakably antiquated when shuffled into a year full of superhero films. Was Kong doomed to feel quaint in the 21st century?

2016 also saw the release of Toho’s own revival of Godzilla, Shin Godzilla (2016), and quite honestly it blows the Legendary Pictures version away. The Hideaki Anno & Shinji Higuchi directed film would prove that it was still possible for these big screen monsters to be relevant, awe-inspiring, and meaningful in the 21st century. The film would see an unprepared government bureaucracy struggling to keep up with the disaster incarnate that is Godzilla. Godzilla transforms through multiple stages, growing larger and more dangerous, only being stoped on the cusp of becoming something potentially apocalyptic. I think within that there is an implicit parallel to the 2011 earthquake which led to a tsunami, which led to the nuclear disaster of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. It’s also perhaps the scariest Godzilla has been since the original 1954 film, showing that what made the original a classic is well-understood by the makers of Shin Godzilla, and that those qualities can still make for an impactful film. It’s a real work of art. Would it be too much to hope for something comparable for Kong?

There was also a real life incident which weighed on my mind in the lead up to the release of Kong: Skull Island…

In 2016, during a trip to the Cincinnati Zoo, a three year-old child left his mother’s sight for just a moment and slipped through a fence into the gorilla habitat, tumbling fifteen feet into a moat down below. A silverback gorilla named Harambe went over to investigate the intruder who was flailing in the water. Onlookers above yelled and made noise which added confusion and tension to the situation from the gorilla’s perspective. Perhaps with the intention of getting the child away from all the noise, the gorilla pulled him very quickly through the water, deeper into the enclosure and onto a dry area, stopping along the way to stand the boy up and seemly checking if the child was alright. The gorilla then stood over the boy in what some have interpreted as a protective gesture before Cincinnati Zoo officials made the decision to shoot the gorilla, killing him with a rifle shot to the head. The child managed to make it through all this without any serious injuries, and apparently the barrier to the gorilla enclosure has since been updated to prevent such a thing from happening again. If you’re reading this you’re probably already aware of the unfortunate incident as it became one the biggest cultural moments for gorillas in recent memory.*4 There have been a lot of varied and impassioned opinions on where blame should be apportioned, though it seems to me the sort of tragedy that Merian C. Cooper might have classified as “killed by civilization.” Would I even want to see a new film where a gorilla is portrayed as a monster and shot? Would anyone?

When Kong: Skull Island released in 2017 all those questions would be answered.

Brought in to direct Kong: Skull Island would be Jordan Vogt-Roberts. His first feature film, the charming The Kings of Summer (2013), about a trio of teenagers who decide to run away from home to live in the wilderness, would end up being a hit for an independent film and bring him to the attention of major studios. There’s a recent trend where these sorts of studio films that cost well over a hundred million dollars, scooping up filmmakers that are fresh to the industry after making a lower budget or independent hit. Perhaps one reason this is done is to have a director for a producer-driven project who can easily be pushed around, milked for critical clout, and then blamed if anything in the film doesn’t turn out. Having said that, there’s a surprising amount of Jordan Vogt-Roberts’ personality and artistry that comes through in the film. While it probably goes without saying that he did not have unlimited creative freedom, he really does seem to be cut for making a film on this scale. In the introduction to The Art and Making of Kong: Skull Island book, Vogt-Robers would write “After I was done with The Kings of Summer I wanted to make a big movie because I grew up on big movies. The only films I had access to as a kid were studio movies and they were big and great. Full of character and full of worlds that you hadn’t seen before and the spectacle felt special.” He would elaborate on his modern blockbuster-making ethos, adding, “In a world where everything is streaming and is instantly accessible, we tend to consume something and then forget about it immediately. How often do you start messing around with your phone when streaming a movie at home? The landscape is changing in incredibly exciting ways, and thus I truly believe movies need a proper reason to be on the big screen – now more than ever. The reason I say this is because a core conceit with designing this movie from the ground up was driven by this changing world. This led to a couple of key principals we used so that this film felt like nothing people had seen before. 1) We must strive to elevate beyond expectations. 2) I feel most big movies are almost entirely interchangeable with their design work and set pieces. I wanted everything to feel unique to this film. Things that could only exist in this film.”

Vogt-Roberts was not interested in the proposed 1917 setting for the story, feeling that it wasn’t removed enough from the 1933 setting to properly distinguish itself from Jackson’s version. Instead he pitched that the story be moved to the 1970s, and the studio agreed. While on paper a 1970s-set King Kong film is something we’ve seen before, Kong: Skull Island bears little resemblance the Dino De Laurentiis’ remake of King Kong. Vogt-Roberts was interested in the period because he viewed it as a time when the world was rapidly being mapped by satellites, and the last days where something as mysterious and fantastical as Kong’s island could still exist. He would describe it as “the period of time when science and myth started to wage war with each other.”

Vogt-Roberts would also bring with him some new and offbeat influences for Kong, citing inspiration from the New Korean Cinema movement, including Park Chan-wook’s Oldboy (2003) and Kim Jee-woon’s The Good, the Bad, the Weird (2008), as well as Japanese manga and anime influences like Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira, and the works of Hayao Miyazaki. There was even some Japanese video game influence, like the acclaimed Shadow of the Colossus (2005) and Ōkami (2006). The result of these influences is a Kong film that feels dramatically rejuvenated. There are still of course plenty of homages to Kong’s previous films, like Kong fighting a giant octopus as he did in King Kong vs. Godzilla, or being wrapped up in the chain of a ship anchor that he must break free from in a moment that is reminiscent of Kong breaking his chains in the original film. Kong: Skull Island never feels burdened by these homages in the way that Peter Jackson’s remake did though.

Kong: Skull Island is also set against the backdrop of the tail-end of the American-Vietnam War which gives it a political dimension and a shift towards a genre of war films like Apocalypse Now (1979), which distinguishes it from the misty fairy tale romance of the ‘70s remake. Vogt-Roberts would elaborate further, writing, “… this time period serves as a perfect mirror for the cultural and political climate happening Stateside. The world at this time was spinning out of control. The constructs of the old world were crumbling. Wars we couldn’t win, oil crises, sexual revolutions, and civil unrest. In a way, the island could be viewed as a sanctuary, untouched by man… A place that offered respite from the terror man had inflicted upon the rest of the world.” This interpretation of Skull Island, secluded from modernity, is not simply a home for horrors, but also a place of striking beauty. Much of the film’s shooting would be done on location in Vietnam, using it as a stand-in for Skull Island, and its natural landscapes has a majesty that is entirely different than the concept-art-come-to-life approach of Jackson’s version. It gives a solid grounding to some of the film’s more stylized and fantastical elements. Jordan Vogt-Roberts would end up loving Vietnam so much that he would even move to Saigon to live as an expat after the film’s completion.*5

This take on Skull Island also forgoes the dinosaurs entirely, a conscious decision to distinguish itself from Jackson’s remake as well as the recent reboot of the Jurassic Park franchise, Jurassic World (2015). However, unlike the 1970s remake, there’s no shortage of compellingly monstrous fauna. Really it’s a cornucopia for fans of movie monsters. Some pose threats to the human intruders, like a giant spider whose legs blend in with a bamboo forest, and impales one soldier in an unexpected homage to the notorious 1980 film Cannibal Holocaust. Other Skull Island creatures are depicted as benign, like the giant walking stick insect or gargantuan water buffalo. They’re just a part of the ecosystem of Kong’s kingdom.

The monsters that pose the greatest threat to both the human characters and Kong are the so-called “Skull Crawlers.” They’re a reimagined version of a strange two-legged lizard creature that can be seen very briefly in the original King Kong, one of the few from the lost spider-pit sequence to not be entirely excised from the film. Here they’re characterized as dangerously predatory monsters that typically hibernate in subterranean vents, but were riled up when intrusive scientists and their military accompaniment used seismic explosives to map the geology of Skull Island. Kong can handle most of the Skull Crawlers, but there’s a “big one” which is powerful enough to challenge Kong for domination of the island.

As for Kong himself, this time he’s depicted as the protector of his island. A living mountain, and a stoic and lonely king, maintaining the natural order of things. It’s also worth pointing out that Kong is no longer a herbivore, eating the aforementioned giant octopus. Design-wise, Kong actually looks much like he did all the way back in 1933, though considerably larger (he’s about a hundred feet tall here), and with perhaps a few nods to his classic Toho appearance incorporated as well. Senior visual effects supervisor Stephen Rosenbaum would highlight how dated design quirks were treated as canonized Kong anatomy; “We intentionally preserved Kong’s disproportionately large head, large eyes, elongated teeth, and big bulbous brows.” Kong also walks on two legs once again, with Vogt-Roberts explaining, “The bipedal element to me reinforced that mythic and god-like quality as it towers over them, and it doesn’t feel necessarily primate all the time.”

Up until this point, Kong’s visual evolution had seemed to be an occasional stumbling march toward gorilla verisimilitude, culminating in Jackson’s remake where Kong’s appearance is at its closest to what an actual giant gorilla would be. This return to a design that evokes a more dated understanding of gorillas could have easily seemed like a step backwards, and yet it doesn’t. I think it works because it comes across as such a strong declaration that King Kong is not a gorilla, he never was a gorilla. He may resemble one, but he’s a monster… he’s a myth.

While the special effects used this time around to bring him to life are perhaps no longer ground-breaking, King Kong looks absolutely outstanding. The digital effects are certainly top-shelf work, done by Industrial Light and Magic (the company founded by George Lucas for Star Wars), creating 1,048 immaculate digital effects shots for the film. The level of detail can be quite astonishing, like for example in a close-up of Kong’s hand, it’s possible to see all of its wrinkles and lines, fur singed by napalm, and the many, many cuts he’s accumulated accumulated throughout the film.

Probably the best showcase of the film’s animation is in the final battle between the giant Skull Crawler with its bizarre anatomy and the anthropoid Kong. While there’s a trend in films with extensive computer generated effects, of using darkness and partial effects like smoke to mask any weaknesses in their CGI monsters, Kong: Skull Island lets this fight scene play out in clear early morning light, making it possible to marvel at just how great these digitally-created creatures look. There’s an impressive sense of scale and movement to the creatures that’s expressed in the fight scene too. Occasionally physical reality is bent into favour of visual impact. In an article by Ian Failes for Cartoon Brew titled, “Why the Character Animation in ‘Kong: Skull Island’ Was Done Differently Than You Think,” ILM animation supervisor Scott Benza would explain, “With a character that’s 100 feet tall, if it was actually moving in a way that was physically plausible, it would be a very slow-moving kind of uninteresting thing to look at. If Kong was really close to camera we felt like we could get away with a faster moving performance. There’s a scene at the beginning of the movie where he’s coming up over a ridge and all you see is a giant hand close to camera. He reaches up and plants his hand, and it’s probably moving at 80 or 90 miles an hour, but given the scale of it and the fact you only see the hand, we found that you could get away with that speed.”

Overall the film very expertly gives a sense of enormity to its giant monsters, and beyond that is often playful in its presentation of scale. For instance there’s a visual connection made between the military helicopters the human characters arrive on and a dragonfly, only to soon see Kong destroy the helicopters as if they were insects to him. Then of course the human characters are faced with giant bugs, which furthers this visual motif.

I don’t want to neglect the human element of the film, but I think there is a common issue amongst the Legendary Pictures Monsterverse movies of casting some world class actors and then essentially wasting them. There are rough analogues to the main three human characters of the original film, though their presence in Kong: Skull Island can feel hollow. Brie Larson plays a war photographer named Mason Weaver, and while she’s the closest the film has to an Ann Darrow, there’s no romantic undertones to her relationship with Kong. Maybe Kong is better for it, since he actually survives this film, and also generally it’s perhaps a step out of the shadow of the original film. It does leave Larson’s connection with Kong feeling fairly muted in contrast to previous leading ladies in Kong films though. Tom Hiddleston plays a survival expert named James Conrad, loosely in the mould of Jack Driscoll. Again, despite being front and centre in the film, I think his character also falls flat. Perhaps most egregiously wasted is the superb John Goodman, who plays a filmmaker and seems to be set up to be the Carl Denham figure of the film, but who ends up having very little to actually do. By about the time of his death scene (which is honestly a thrilling moment) I had forgotten that his character hadn’t been killed off earlier. Despite all of that, I think Kong: Skull Island still has a few great characters and performances which effectively give it a humanity that elevates it above the other Monsterverse films.

The first to mention would be the character of Lieutenant Colonel Packard, who comes across like a revamped version of Lieutenant Colonel Nevitt from King Kong Lives, given adequate depth, nuance, and motivation. A veteran of the American-Vietnam War disappointed with the outcome, after his soldiers are killed by Kong, Packard sets out to kill King Kong. The role was originally offered to J.K. Simmons, but ultimately went to Samuel L. Jackson, who brings his typical gravitas and intensity to the character, as well as a sense of righteousness that keeps Packard from ever feeling like a clear-cut villain. He’s someone who on screen can believably stare-down a one hundred foot tall monster. There’s something of Captain Ahab from Herman Melville’s novel Moby-Dick to his futile attempt to exact revenge on an enormous animal.

The character of Packard also connects directly with an underlying political theme in the film. I’ve seen Kong: Skull Island referred to as a “Vietnam War allegory,” though I took something a bit different away from the film. With the end of the American-Vietnam War seeing Packard then throw himself into another un-winnable war with Kong, I rather think this creates a parallel with the American extraterritorial conflicts to follow the American-Vietnam War. The scene where he comes close to killing Kong with napalm, only to allow the giant Skull Crawler to emerge to the surface, does hint at the ways American military intervention has disrupted the power structures in other countries. Also with events like the recent handing over of Afghanistan to the Taliban in 2020, lines in the film like “And we didn’t lose the war, we abandoned it,” certainly have a fair bit of sting that I think makes the film more timely than it may appear at a glance.

Another standout character is Hank Marlow, a pilot who was shot down during the Second World War, stranding him and an enemy Japanese pilot named Gunpei on Skull Island. The existential threat of Kong makes the two enemies become close friends, though eventually Gunpei dies and Marlow is left to survive on Skull Island. With the arrival of outsiders nearly three decades later he’s given the opportunity to finally escape and return to his wife, and the son he never met back in the United States. A number of his scenes also bring to mind classic films like Robert Aldrich’s The Flight of the Phoenix (1965) and John Boorman’s Hell in the Pacific (1968). The out of time soldier surviving while isolated on the island does also recall the true life story of Hiroo Onoda, a Japanese officer who did not believe that the Second World War had ended, and continued to survive and and wage a guerrilla campaign on Lubang Island in The Philippines all the way into the 1970s, when he was finally convinced that the war was long over, and returned to society where he fit in about as well as a time traveler could. Marlow is played by John C. Reilly, and like Jackson, he also wasn’t the first choice for the role, with it initially being offered to Michael Keaton. Reilly is a great fit though, flexing both his dramatic and comedic abilities. I think he can be described as the heart of the film.

Another human aspect of the film that fares well are the Skull Islanders, here given their own indigenous name of “Iwis.” Even without spoken dialogue, they have strong presence in the film, depicted as a peaceful culture that has found a way to balance their lives with the presence of Kong and the other monsters, which provides a contrast to Packard’s disruptive approach. It’s a very dignified depiction which comes across as perhaps a deliberate response to how the Skull Islanders had been depicted in Jackson’s remake.

Also I would be remiss if I failed to mention Shea Whigham’s character, Captain Cole. He has some of the best comedic moments in the film, and his death scene is the unquestionable standout moment as far as the film’s visual wit and dark sense of humour go. In what at first seems to be building towards a clichéd moment, he attempts to heroically sacrifice himself to bring down the giant Skull Crawler with grenades, only to be easily thwarted as the beast swats him away, to explode pointlessly against a mountain face.

The film isn’t without its flaws. The most glaring of which Vogt-Roberts was quick to point out himself in good humour while making a guest appearance on “Honest Trailers,” a YouTube video series. Most notably those flaws would be the film having narrative structural issues, and characters that should have been cut or consolidated. I think it’s easier to let some of its issues slide because the film has perhaps lower ambitions than say Peter Jackson’s King Kong, but manages to more than deliver as a piece of popcorn entertainment. As Vogt-Roberts describes it in that YouTube video, Kong: Skull Island is closer to Paul W.S. Anderson’s Alien vs. Predator (2004) than to James Cameron’s Aliens (1986).*6 I don’t think that should be taken as a diminishment of the film’s artistry either. It’s colourful and visually imaginative, full of memorable set pieces and action scenes. Most of all it’s just a huge breath of fresh air for King Kong as a character. It’s a reminder that there are potentials and possibilities for Kong other than simply telling the same story over again and again.

The box office success of Kong: Skull Island would seal the deal; King Kong and Godzilla would have their rematch in just a few short years.

In the meantime Kong would have a proper debut on Broadway with the musical, King Kong. A King Kong Broadway musical honestly seems like such a no-brainer that it might be considered surprising that it took until 2018 to happen (although supposedly being one of the most expensive Broadway productions ever is probably a good answer as to why not). The show starred Christiani Pitts as Ann Darrow, and she’d share the stage with a truly incredible 20 foot-tall, 2000 pound King Kong marionette puppet which required 13 crew members to move, and an animatronic face and head remotely operated to give Kong a wide range of expressions. Despite the music itself being heavily criticized and the consensus from people I’ve spoken to who had seen the show that it was “too loud,” personally I count not having seen the show for myself as one of my big regrets of the past few years.

There would also come another Legendary Pictures Godzilla film, Godzilla: King of the Monsters (2019). With its gaudy visuals, overwrought family drama, and extensive monster action sequences that struggle to leave an impact, it comes across as a bit like an overcorrection for the previous Legendary Godzilla. It does at least have a pretty fun homage to Akira Ifukube’s original score for Godzilla.*7 It would also bring in popular streaming series Stranger Things star Millie Bobbie Brown as a lead, hinting at a push to a more child-friendly audience. Kyle Chandler plays the role of her father, so he’s once again surrounded by giant monsters. The film would also see updates of other classic Toho monsters including Mothra, Rodan, and King Ghidorah. Personally I think the Legendary redesigns can be a bit hit or miss; while I don’t particularly like the look of the small-headed crocodilian Godzilla or aggressive-looking large-clawed Mothra, I’d say that Rodan and King Ghidorah are a wonderful reinterpretation of the intent of their original designs, using the possibilities of computer animation to emphasise their inhuman anatomy.

Godzilla battles Ghidorah for supremacy over the other monsters. The climax even pays homage to Godzilla vs. Destroyah with Godzilla entering a state of meltdown (an idea you may recall originated with a never-realized Godzilla vs. Mechani-Kong film). Godzilla defeats King Ghidorah, and apparently earns his title of “King of the Monsters.” Now everything was in place for Godzilla vs. Kong.

Adam Wingard was hired to direct Godzilla vs. Kong, giving him a new opportunity to properly bring the giant terror ape into the 21st century. Advertising played up the idea that this time there would be a definitive victor, and it seemed this would be the grand event film and possible finale to Legendary’s Monsterverse.

The road to the finish line would prove to be bumpy for Godzilla vs. Kong. The film was set to be released in May of 2020, before being pushed first forward to March, and then back to November of 2020 (with rumours suggesting the film may have been retooled in response to negative criticism for Godzilla: King of the Monsters). When the COVID-19 pandemic plunged the world into a state of disruption and uncertainty, the film would be pushed back to all the way to a May 2021 release date, in hopes that some degree of normalcy may have returned by then. The situation was further complicated when Warner Brothers made a deal to release their entire slate of films for the year simultaneously in theatres and on the streaming service HBO Max. For a moment it looked like it could be the death knell for the theatrical experience. The release date was also moved up once again to March of 2021. It’s difficult to parse exactly how this chaos might explain certain aspects of the final film, but it does seem worth taking into consideration.

The plot is kicked off by Godzilla going on a destructive rampage, with offscreen the implied killing of other monsters. Millie Bobby Brown reprises her role from Godzilla: King of the Monsters, working to get to the bottom of why Godzilla has taken a turn for the villainous. She shares the screen with fellow young-adult actor Julian Dennison, who is probably currently best known for Hunt for the Wilderpeople (2016), and together they join up with Brian Tyree Henry who plays a podcaster conspiracy theorist, and all together they might be considered “Team Godzilla.” Kyle Chandler also reprises his role from Godzilla: King of the Monsters, though he has next to nothing to do in this particular film, and doesn’t really have any interaction with Kong in this new continuity. It strikes me as a missed opportunity that he is never gives the chance to give some wink or nod to the audience to remind of his role in Peter Jackson’s King Kong.

Meanwhile a giant dome has been built around Skull Island, isolating Kong, though it’s only a matter of time before Godzilla challenges him. Apparently all of the Iwis of Skull Island have been killed in a natural disaster, save one, a young girl named Jia, who communicates in sign language. She has been adopted by a primatologist studying Kong named Dr. Ilene Andrews. Dr. Andrews is played by Rebecca Hall, and Jia is played by newcomer Kaylee Hottle (one of two hearing impaired actresses to star in the film, the other being Millie Bobby Brown). With the help of a geologist named Dr. Nathan Lind, played by Alexander Skarsgård, they decide to relocate Kong to a newly discovered hollow interior of the Earth where an isolated ecosystem of monsters live, and where there may be some power source that could stop Godzilla. I want to emphasize that I think these actors are all excellent (Skarsgård would also play a supporting role in Hall’s impressive directorial debut, Passing the same year), but the film often struggles to give them things to do beyond delivering exposition and reacting to the monsters doing what monsters do. At least there’s a nice little family dynamic that forms with “Team Kong” though.

Kong’s appearance has been tweaked since Kong: Skull Island. He now has a beard to show his age, has a bulkier physique, and most notably has more than tripled in size. He’s been scaled up to the largest he’s ever been, presented as being about a quarter as tall as the Empire State Building. Despite this absurd size, often I find that sense of scale that was expressed so well in Kong: Skull Island is lacking here. There’s often a detachment from humans to give a sense of scale, and a use of framing that would be more typical of a regular-sized person. It contributes to a less impressive Kong despite his increase in size. The rationale for this size increase was that he needed to fight Godzilla who has also been scaled up for the Legendary films in order to look appropriately imposing in a modern world where skylines have risen. I can’t help but think that it was a bit of a missed opportunity to not have played into Kong’s characterization as an underdog in this film by putting him at a severe height disadvantage to Godzilla. While the use of suits for their 1960s confrontation necessitated Kong being scaled up to a comparable height with Godzilla, with the availability of CGI, it could have been interesting to see a Kong maybe only a third of the size of Godzilla, who must rely on nimbleness and guile to fight. As it is, how exactly does one make a skyscraper-sized ape feel like an underdog? Adam Wingard’s solution was to draw inspiration from action films like Lethal Weapon (1987) and Die Hard (1988) which emphasized the vulnerability of their action heroes, to depict a Kong who is often only surviving by the skin of his teeth.

I’ve enjoyed some of Wingard’s previous films, particularly You’re Next and The Guest (2014), but it’s a little difficult to gauge just how much of his directorial voice comes through in the film. The dark humour, subverting expectations, and playful genre-bending that made those films appealing isn’t really present here. Part of that is probably due to the tone of the film. The presence of juvenile actors in major roles is probably already a tip-off to the film’s child-friendly approach, and while the 1962 King Kong vs. Godzilla set a precedent for that, it’s hard not to overlook how Godzilla vs. Kong is perhaps a little too infantilized, particularly when faced with a plot that feels both drastically over-simplified and requiring an extra-large helping of suspension-of-disbelief, even by the standards of giant monster movies. I do think it’s been effectively done in the past where King Kong and Godzilla films have taken an approach that can still appeal to children without alienating adults.

While transporting Kong on an aircraft carrier, it is revealed that Jia has taught him a little bit of sign language, so Kong is now able to communicate. Kong learning sign language may have been included for the benefit of the audience being able to better connect with this more heroic version of the character, and perhaps also to distinguish him from Godzilla in a bit of a “brute force vs. brain power” dynamic, though its inclusion is certainly one of the most interesting developments in his characterization.*8

Godzilla locates the convoy of ships that are transporting Kong and attacks, setting off the first of two fight scenes between the giant monsters. The film’s post-production work was completed remotely, with the visual effects team working from home due to pandemic lockdowns and other restrictions, and I think that’s reflected in that the quality of digital effects is generally not quite up to the standard set in Kong: Skull Island. Having said that, this is a pretty great looking sequence. I’d go as far as to say the standout moment of the film. There’s a definite satisfaction that comes with feeling the mass of Kong’s titanic punch collide with Godzilla’s undersized head. With this battle on the Ocean, the semi-aquatic Godzilla has a distinct advantage though. Kong is forced to jump from one aircraft carrier to another, and then nearly drowns after being wrapped up in Godzilla’s tail and dragged down into the water. Godzilla easily wins, and the convoy is only able to get away with Kong by playing dead.

Inside the Hollow Earth, Kong has a scuffle with a giant flying snake, and it seems to be generally a suitable place for monsters to live. There’s also some evidence of an ancient battle fought between Kong’s and Godzilla’s ancient ancestors. Kong even picks up an axe that was made from the dorsal plate of some precursors to Kong, which soon comes in handy because up on the surface, Godzilla has sensed where Kong is and uses his atomic breath to tunnel a hole through the Earth’s crust that Kong can climb up from.

Their second fight is in a neon-lit version of Hong Kong, and the playing field is a bit more even with tall buildings for Kong to climb. Again I can’t help but notice the visual absurdity of how much larger Kong has become as he hangs off of skyscrapers not much smaller than himself. Apparently Kong’s newly-found axe has the ability to absorb a blast from Godzilla’s atomic breath and store it as a charge, which gives him an advantage. At first it seems Kong has Godzilla on the ropes, but then he stops playing around and still easily overpowers Kong. Godzilla stomps on Kong’s chest causing his heart to fail. Godzilla is the definitive winner.

Within the world of the film, Godzilla’s victory makes a certain sense. After all, Godzilla is a nuclear-powered dinosaur impervious to human weapons while Kong has been brought down by those weapons in the past. Outside of that, on this outcome it’s perhaps worth noting that unlike their shared film in 1962, this time Godzilla would receive top billing over Kong. That’s perhaps a reflection of how Godzilla had eclipsed Kong in popularity since their last fight, likely due to appearing in films far more regularly in the decades since their last on-screen conflict.