Kong Jubilee: A 90th Anniversary Celebration – Part 1.

There’s a brief moment in 2021’s Godzilla vs. Kong when, after vanquishing a bizarre and fearsome opponent, King Kong slumps down in exhaustion to rest against a skyscraper. It may be the most remarkable beat in the film because, for that brief moment, you can feel Kong’s age. You can practically hear him say, “I’m too old for this shit.” In that moment, you can feel the weight of a career as long as a lifetime on the shoulders of one of the genuine icons of cinema. Of course, being around as long as Kong has calls for a look back at the giant ape’s cinematic reign, with all its triumphs, tribulations, and tragedies.

It would be reasonable to start at the beginning, but I hope you won’t begrudge me going back to a time before the beginning, to the primeval misty milieu from which Kong would conceptually emerge…

On The Origin of Monsters.

What is King Kong anyway? You know the answer. It’s obvious, right? He’s a giant gorilla! Well, it’s worth making the distinction that “gorilla” can mean two different things here. There’s “gorilla,” the real-life endangered, herbivorous great ape, which is one of the closest living relatives to humans. There’s also “Gorilla,” the mythic monster, who was born of the former’s elusiveness to science.

The first written account of gorillas may have come from 2,500 years ago, by a man called Hanno the Navigator. He adventured from his native Carthage (located in present-day Tunisia) down the coast of western Africa, and saw what he described as a tribe of uncivilized, hairy people, whom his guides called “gorillai.” Hanno’s expedition would kill three females and bring their pelts back to Carthage as evidence of the creatures’ existence. Those pelts and what they proved would eventually become lost to the world when Carthage’s rivals, the Romans, destroyed the city.

After that, gorillas would be a myth to those who lived outside their immediate territory. They were typically depicted as violent sub-humans who would murder men and abduct women for lascivious purposes. They were creatures of dark folklore and nightmare, completely unlike the gentle creatures of reality.

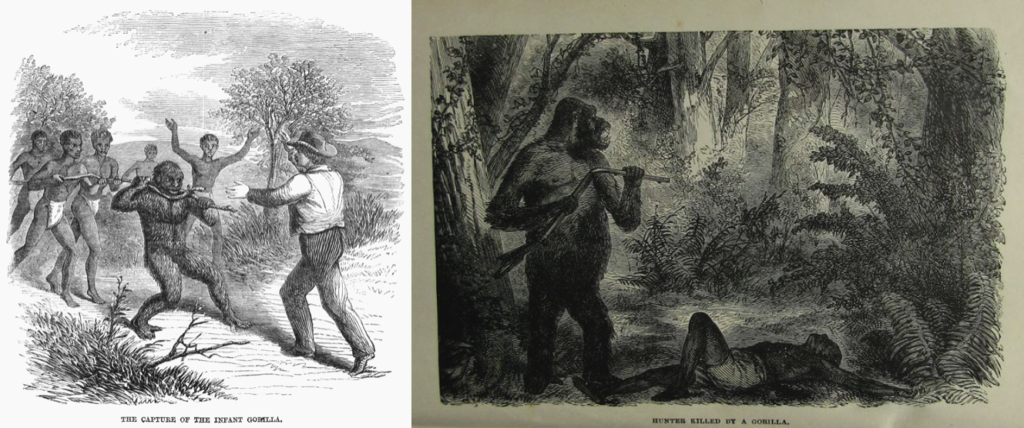

Western lowland gorillas would not become known to the scientific establishment until 1847. Their rarer cousins, Mountain Gorillas, would not be confirmed to exist until 1903. Even then, the elusive and shy behaviour of gorillas meant that inaccurate descriptions of them would continue to persist. How they were imagined in the public consciousness was much more like what someone today might imagine when asked to picture a Sasquatch or a yeti. For example, they were often erroneously described as being fully bipedal, while in reality gorillas are quadrupedal, with their distinctive knuckle-walking. Artistic renditions from the 19th century also often give them more hominin proportions, while dramatically exaggerating certain details, like extending the gorilla’s canine teeth into more prominent fangs.

These 19th and early 20th century depictions and representations all add up to a creature that isn’t truly a gorilla, even though at a glance a layman might recognize it to be one. The definitive depiction of that era’s notion of the gorilla as monster would be Emmanuel Frémiet’s staggering full-scale sculpture, Gorille enlevant une femme (1887). In its creation, Frémiet had revised an 1859 sculpture that brought him notoriety for presenting it in relation to Darwin’s evolutionary theory, with that version having been destroyed in 1861.

Even as scientific understanding of gorillas gradually progressed, they were still seen as a creature destined to be forever wild and mysterious to us. They were not only seen as untamable but as creatures that could not exist in the civilized world. In 1915, famed American zoologist and conservationist William Temple Hornaday, went as far as to say that, “There is not the slightest reason to hope that a gorilla, male or female, will ever be seen in a zoological park or garden.” However, one place where a gorilla could be seen was in a movie theatre. They were realized with actors in not-particularly convincing costumes, and portrayed as the monster variety of gorilla. They were used for shock value, and would be a prominent fixture of a popular, though somewhat dubious genre that emerged in an unrestrictive era of Hollywood. Some notable examples would be Lorraine of the Lions (1925), The Gorilla (1927), and most notoriously of all, the lurid exploitation film Ingagi (1930). Ingagi proved to be unexpectedly lucrative for its exhibitor, RKO Pictures.

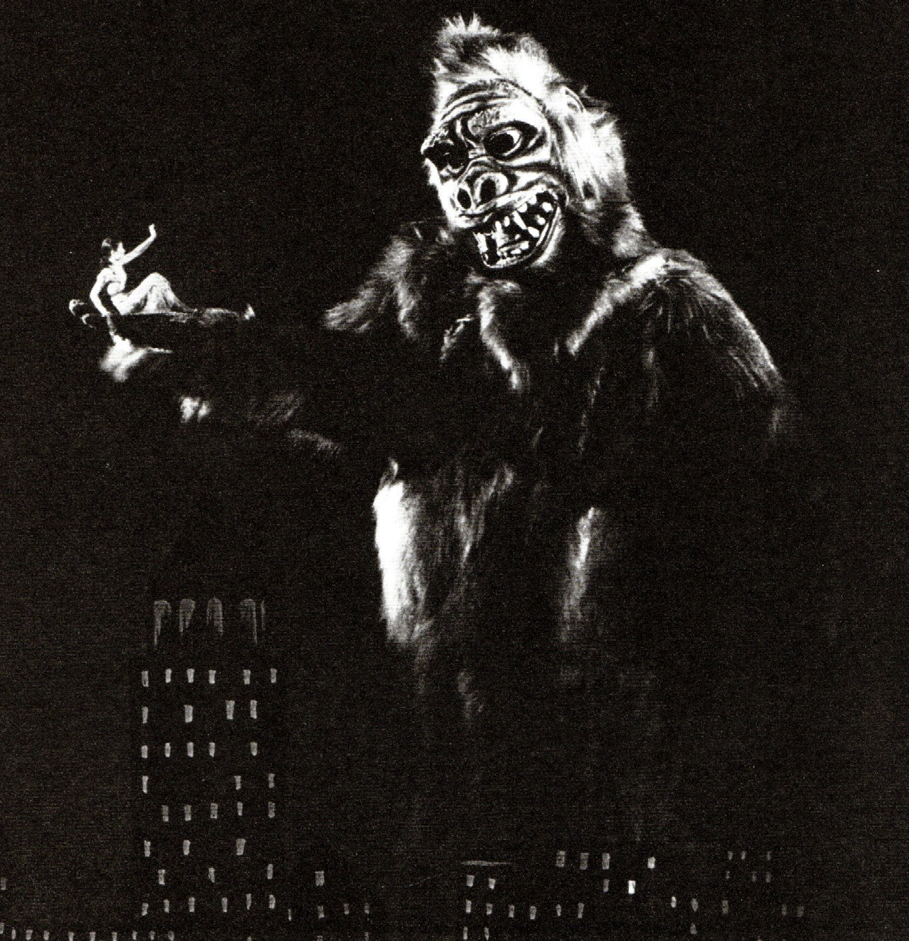

When King Kong burst onto cinema screens in 1933 in the eponymous film, he would be both a part of that pop cultural gorilla lineage and also unlike anything audiences had seen before. But how did he get there?

King Kong I.

Numerous creative people would have a role in bringing Kong to life, but Merian C. Cooper might be considered principal amongst them. His life story is eventful enough to tempt me to take a long tangent, but I don’t want to lose sight of this being Kong’s story, so I’ll try to be brief. Cooper might succinctly be described as a man who lived an adventurous life. He survived being shot out of the sky during his time as a pilot during the Great War (an incident that left him scared by burns). He would also fight against the Soviet invasion of Poland in 1920, which landed him in a Soviet prison camp that he would eventually escape from. That was exciting enough to be the inspiration for Leonard Buckowski’s now-lost 1930 Polish film, The Starry Squadron.

Cooper would find a kindred adventurous spirit in Ernest B. Schoedsack, a cameraman for the United States Army during the First World War. Cooper described him as “a goddamn brilliant man.” Together they embarked on a creative partnership in filmmaking with, “Make it distant, difficult, and dangerous” as their motto. They would shoot a series of “natural dramas.” These were a blend of nature documentary, ethnographic filmmaking, and fictional adventure storytelling. In shooting these films they’d travel to locations found in modern-day Ethiopia, Iran, and Thailand. The two complimented each other well, with Schoedsack saying, “Each of us made up what the other lacked.”

In 1929, Cooper & Schoedsack made the jump to studio fiction filmmaking with an adaptation of the classic novel The Four Feathers. It was a story that held great personal importance for Cooper because it nurtured his soul during his time spent in the Soviet prison camp that he had escaped from. It would feature Canadian-American actress Fay Wray as its leading lady and have an ambitious young David O. Selznick as its producer. Studio interference ultimately made it an embittering experience for Cooper, but it was around this time, while observing a family of baboons while on location in Africa, that he began to daydream of making a film about a “giant terror ape.”

Merian C. Cooper had been fascinated with gorillas since he was six years-old and his great uncle gifted him a copy of Paul Du Chaillu’s sensationalist non-fiction book, Explorations and Adventures in Equatorial Africa. Cooper would grow up to be a little disappointed to find they weren’t quite as giant as the image those books conjured in his mind, but he still held onto that child-like sense of wonderment with the animal. However, a key inspiration for his creation would come from a different species entirely. That creature also happened to have a quasi-mythical status at that time; the Komodo Dragon.

The famously large monitor lizards had only become known to scientists in the 1910s, and were initially mischaracterized in popular culture as the living descendants of dinosaurs, or holdovers from a more primordial age. The first to successfully capture Komodo Dragons, both on film and also in the more literal sense, was a zoologist and filmmaker (and inventor of shark repellent) named W. Douglas Burden and his then-wife Katherine C. White, who travelled to the remote island of Komodo in 1926. Burden managed to bring two living specimens back with him to New York City, but the dragons died shortly after. As it would happen, Cooper was friends with Burden and found himself moved by the tragedy of those Komodo dragons. He would quip that they were “killed by civilization.”

Cooper envisioned his giant terror ape battling Komodo dragons before being captured and brought to civilization, where it would go on a rampage. The idea that would be the cherry on top came to Cooper while he was daydreaming, looking at New York skyscrapers. His giant ape would climb the tallest building in the world before being gunned down by war planes. Cooper had considered utilizing footage of authentic gorillas and Komodo dragons, but failed to secure financing for his planned trips to Africa and Komodo Island to collect footage. He’d say, “Everyone wanted me to put a man in a gorilla suit, and that would have just been horrible.” His ambitious idea had all the hallmarks of a pipe dream, but an opportunity to realize his vision would soon present itself.

In 1931, when the Depression turned out to be “Great,” Cooper helped David O. Selznick get a job at RKO Pictures, where Selznick quickly rose to prominence, becoming the vice president in charge of production. It would be a major stepping stone in Selznick’s titanic career. Selznick would soon pay Cooper back by bringing him on as an executive at RKO, where he would begin production on an adaptation of the short story, The Most Dangerous Game, with his pal Ernest B. Schoedsack brought on to direct, and would include Fay Wray and Robert Armstrong in its cast. It tells the story of a big game hunter who has turned to hunting people for sport on his isolated island. With money being tight at RKO and everywhere else, it would inevitably share much of its cast, crew, and sets with King Kong. Cooper was also tasked with getting a film production that had run over budget and behind schedule, back on track. It was for a film that was to be titled Creation and would have been about a group of people from a cruise ship who discover an island where a myriad of extinct creatures still live. Its director was Harry O. Hoyt, who had previously directed the 1925 dinosaur extravaganza, The Lost World. Cooper was completely unimpressed with the Creation story, describing it as “just a lot of big beasts running around.” However, he was impressed by the special effects work that had been created by Willis O’Brien.

Willis O’Brien was a man who had gone through many careers, including cowboy, boxer (something he would find was a mutual interest of Merian C. Cooper’s), guide for archeologists, cartoonist, and sculptor. He would eventually find his calling as a stop-motion animator. His earliest short film, which features a giant ape fighting a dinosaur, would attract the attention of Thomas Edison and kick off his career. O’Brien would advance the craft by developing compositing techniques to integrate his miniature animated creatures with live action. A great early example of that would be his work on The Lost World, which climaxes with a spectacular sequence of a pissed-off sauropod rampaging through London, where in some shots you can see both people and the dinosaur moving about in the same frame. I was charmed to read that at least some people found it convincing enough to leave theatres in 1925 thinking that somehow they really had seen a dinosaur, or at the very least something life-size. O’Brien’s preliminary work on Creation pushed the boundaries of special effects even further, and in him, Merian C. Cooper found what he needed to bring his giant ape film to life. Cooper scrapped Creation, but repurposed much of the work that had gone into it. With the help of a test reel created by O’Brien, his giant terror ape film was finally approved for production, and he would hit the ground running.

The film would be written in a whirlwind, passing through many hands in a short amount of time.*1 There would also be a tie-in novelization commissioned, with Delos W. Lovelace as its author, set to be published in advance of the film’s release. It’s something that would inevitably complicate the legal ownership over its story and characters.

The final draft of the screenplay would be written by a quick-witted first-time screenwriter named Ruth Rose. Rose was a former Broadway actress who, while working as a zoological writer on an expedition to the Galapagos Islands, would meet and fall in love with Ernest B. Schoedsack. Soon after, the two would be married. Cooper knew that Rose was familiar with what he and Schoedsack were going for, and so he entrusted her to bring the story to a place where they would all be satisfied.

The resulting story is one you’re probably already familiar with.

Carl Denham, a film director with a reputation for recklessness, recruits an out of work and desperate actress named Ann Darrow to travel aboard a ship on an expedition to a remote island where he intends to make a film searching for a mythic being called Kong. Along the way, the hardened first mate named Jack Driscoll is initially cold to Ann, but can’t resist her strength of character and soon falls for her. They arrive on the island to find a tribe of indigenous people (a pastiche of traditional African and Asian cultures) who worship a god-king called Kong. When negotiations with them fail, they capture Ann to offer as a sacrifice to Kong. Kong is of course a giant terror ape, who whisks her away into the jungle. Denham and Driscoll lead an expedition into the island to rescue Ann, but encounter obstacles in the form of a variety of prehistoric monstrosities. An enormous theropod tries to eat Ann, but Kong protects her from the dinosaur and takes a liking to her. Kong takes Ann back to his skull-shaped mountain lair, only taking a moment away from her to fight a giant constrictor snake. Jack manages to retrieve Ann, but an angry Kong pursues them only to end up knocked unconscious by a gas bomb before being captured by Carl Denham. Kong is brought back to New York, where he’s displayed in chains in a Broadway show. An enraged Kong breaks loose from his chains and goes on a rampage through the city, looking for Ann. When he finds her, he brings her to the top of the Empire State Building and carefully sets her down. A squadron of biplanes is sent to kill Kong. He tries to fight them off and even manages to bring one of them down, but the giant ape is no match for the airplanes and their machine guns. Kong gently strokes Ann, and then falls dead to the street below.

It’s often been pointed out that the characters of Carl Denham, Jack Driscoll, and Ann Darrow would reflect the personalities of Cooper, Schoedsack, and Rose respectively. It’s perhaps worth noting that those may not be entirely flattering self-portraits either, with Carl Denham in particular coming across as having a dangerously brash attitude and an exploitative mindset. For those on-screen surrogates, Robert Armstrong would be cast as Denham, and Bruce Cabot as Driscoll. For Ann, Fay Wray would be hired to bring her blend of charm and sophistication to play the out of work actress. Cooper promised her that the role would come with “the tallest, darkest leading man in Hollywood.” This conjured an image of Cary Grant in Wray’s mind, so she was stunned when Cooper unveiled concept art by Mario Larrinaga of the giant ape.

Cooper and Schoedsack would co-direct, with Schoedsack focusing mostly on the dialogue scenes and Cooper focusing mostly on the action and scenes that would integrate special effects. Production would prove to be an incredibly intense and gruelling experience, putting Cooper and Schoedsack’s creative partnership and friendship under much pressure. Not the least to suffer was Fay Wray, whose interactions with Kong required her to perform while doing things like being held high in a giant mechanical hand contraption for hours, or be present for rear projection scenes that required painstaking set-up. Perhaps the most infamous episode was the brutally exhausting twenty-two hour-long shooting day to achieve a brief shot of Kong placing Ann Darrow in a tree. While shooting that scene, there was an intense argument between Schoedsack and Cooper, with Schoedsack unsuccessfully making the case that Fay Wray would appear so small on screen that they could get away with using a double instead and avoid putting her through sitting in that tree any longer. Still, the relationships of those involved managed to hold together, and I think it all pays off, as Wray’s sharing the screen with Kong is what makes her special effect co-star feel so real.

It was perhaps only natural that the introduction of synchronized sound to film would allow for the horror genre’s first true “screams queens,” of whom Wray is certainly one of the best early examples (right up there with Elsa Lanchester’s unforgettable scream in James Whale’s 1935 horror classic The Bride of Frankenstein). Wray’s powerful scream is what announces Kong’s arrival, over 40 minutes into the film, and lets us feel that she’s reacting to something real. It’s as if we’re seeing the giant ape through her eyes. Of course, she keeps on screaming, and as Wray herself would criticize, her character wouldn’t have much else to do for the remainder of the film.

There was some pressure from Selznik to show King Kong upfront, perhaps beginning the film with his unveiling on Broadway, before then flashing back to show how he got there, but I think Cooper and Schoedsack made a wise choice to slowly bring audiences into the world of the film, and gradually build up to Kong bursting onto the screen about 45 minutes into the film.

Kong is certainly more monster than gorilla. He’s giant, though it’s a little difficult to pin down his exact size, with him being deliberately scaled up for the New York scenes to look correctly imposing in the enormous city. He’s exactly the sort of creature that captures the imagination, terrifying, yet majestic, brutal, but also deeply sympathetic. Initially there was some disagreement over how Kong should look, with Willis O’Brien pushing to have him appear more gentle and anthropomorphized and Cooper pushing back, demanding, “the fiercest, most brutal, monstrous damned thing that has ever been seen.” O’Brien tried to argue that that would make it impossible for audiences to sympathize with the creature. Cooper retorted, “I’ll have women crying over him before I’m through, and the more brutal he is, the more they’ll cry at the end.” I think it was perhaps a wise choice to give Kong eye-whites rather than the dark eyes of real gorillas, which allows us to see where Kong is looking and get an impression of what he’s thinking. It’s a physical trait that would stick with Kong for the many films and design iterations that would follow.

There had been spectacular and convincing special effects in films before, but King Kong may be the first special effect to have a soul. There’s the surprisingly human way Kong fights, with his punches and wrestling moves used on the attacking dinosaur (actions that Cooper acted out for O’Brien to use as reference for the scene). There’s an unmistakable innocence to Kong, shown in the way he curiously undresses Ann, or looks at his own blood with confusion after being shot by an attacking biplane. There’s often a dark dimension to that innocence too, reflected in the way he plays with the broken jaw of the defeated dinosaur or the way he casually and non-maliciously drops a woman to her death after realizing that she isn’t Ann. There’s also his trademark chest beating, inspired by the displays of real gorillas, which Kong does first in triumphant victory over a dinosaur and then later in defiance against attacking biplanes. Of course, his violent indiscretions notwithstanding, when Kong dies, we all feel like crying.

There’s also some debate as to what King Kong may represent or be a metaphor for. Of course, sometimes a giant ape is just a giant ape, but there’s the lingering sense that the film is more than just a thrilling adventure. It feels as if it must mean… something. Unlike his eventual on-screen rival Godzilla, who has a consensus of opinion on being an embodiment of nuclear anxiety, the interpretations of what Kong may embody are somewhat more varied.

There is of course the obvious “beauty and the beast” layer of the story, with a beautiful young woman bringing out the sympathetic side to a frightening monster. Within it, a parallel is drawn between Kong and the initially repellant and sexist Jack Driscoll who inevitable softens to Ann’s charm. It might even be a representation of Schoedsack and Rose’s relationship. Schoedsack held a dim view of women after the journalist Marguerite Harrison had to join Cooper and Schoedsack’s expedition to Iran to film Grass (1925) and spoiled the experience. Schoedsack would say, “She didn’t have to make any trouble, but being a woman couldn’t help it. She’s got to have her private tent and her stuff, and half the little money we had, had to be spent on taking her along.” Cooper, who was friends with Harrison would apologetically say, “We didn’t know what hardships we were putting her through.” Eventually, when meeting and falling in love with the adventurous and independent Ruth Rose, Schoedsack would have his opinion on the subject altered.

That interpretation could also easily be flipped to be taken as a misogynistic notion of femininity bringing out weakness in the strong. It’s something that is set up with the supposed Arabian proverb (actually invented by Cooper) that begins the film, and seems to be cemented with the famous final line of the film, “It wasn’t the airplanes. It was beauty killed the beast,” spoken in the presence of a crowd gawking at the corpse of the fallen monster. Of course, that would ignore much of the obvious irony and more subtle touches that pervade the film. After all, that line is uttered by Carl Denham, who, consciously or not, bares the most responsibility for Kong’s capture and inevitable death. It seems there may be something else buried a little deeper in the film.

For some, the fantasy beast’s ascent to the pinnacle of human achievement might represent the economic boom of the 1920s, only to be gunned down and fall to his death in a parallel to the stock market crash that had just plunged America into The Great Depression. From that perspective it’s notable that when brought back to New York, Kong’s humiliation at the hand of the greedy Carl Denham is for the amusement of only those wealthy enough to afford a ticket, with one man quipping in line that the tickets had cost him “twenty bucks,” an exorbitant sum for 1933. This interpretation of King Kong as a critique of a broken promise of prosperity might put the film in conversation with many similarly-themed, tragic rise and fall films about outsider gangsters released during that period, like Public Enemy (1931) or Scarface (1932).

For others, the film’s proto-conservationist themes are most resonant. Skull Island (the name typically given to Kong’s island, even though it’s never given a name in the film) is a wondrous world full of creatures that defy extinction. The island’s indigenous population lives a traditional life in close proximity to those creatures, in something resembling harmony, give or take a human sacrifice. The delicacy of that ecosystem is not to be disregarded. The arrival of outsiders presents as much of a threat to the uniqueness of Skull Island as the creatures that reside on the island present to them. One scene sees Denham and his men come upon a stegosaurus that they cruelly shoot and leave for dead. It feels a little like karmic payback when, in the very next scene, a snarling sauropod mauls one of the crew. Looking at the film that way, Kong would embody the grandeur and majesty of the natural world. His potential for violence only means that humans should treat him with a respectful distance. When Kong ultimately meets its end in the urban world, there’s an upsetting sense that a unique wonder of nature is gone forever, killed by civilization like Burden’s Komodo dragons.

One of the most enduring interpretations is that King Kong is a racial allegory. It could perhaps be a sympathetic metaphor for the history of slavery, exploitation, and cruelty subjected to African-Americans, or maybe a commentary on a lack of acceptance for inter-racial relationships. Quentin Tarantino’s 2009 war film Inglourious Basterds even takes a moment to lay out a version of this interpretation. It’s a notion that is complicated by dehumanizing racist caricatures likening Black people to apes, which were not uncommon at the time the film was released. Merian C. Cooper rejected that particular interpretation of the film, though it may be given some credence by Cooper’s views occasionally reflecting the colonial values of the sort of 19th century “great white hunters” who inspired him. Cooper at the very least grappled with these themes personally, writing in his 1927 autobiography, “The lust of power is in us, we white men. We’ll sacrifice anything for the chance to rule.” Either way, I don’t think it’s much of a stretch to say that Kong might represent “otherness” within American society.

The interpretation of King Kong that I find resonates most (and which I don’t think precludes some of the other meanings mentioned, and may even strengthen them) is that the film is about the nature of show business. After all, if Cooper is Denham, Schoedsack is Driscoll, and Rose is Darrow, then it might follow that Kong is the film itself. Simply put, Kong is filmmaker Carl Denham’s “giant monster.”

When looking at King Kong through that lens, Kong might embody some of the worst and most notorious and life-wrecking aspects of the film industry. It’s possible to see Kong as a leering monster whom young actresses are occasionally sacrificed to, and who maliciously chews people up and spits them out or thoughtlessly tosses them aside. To further complicate that, Kong not only plays the role of the victimizer, but also that of the victim. There are even numerous parallels within the film between Kong and Ann. The most obvious example is Ann’s pose while being offered up in sacrifice to Kong, which is mirrored by Kong being presented in chains to an unforgiving audience. Kong is destined to be martyred for our entertainment, but perhaps with the promise that one day he may return from death for an encore.

Truthfully, I think there’s a little bit of all of these interpretations woven into Kong’s DNA, all revolving around a common spoke of exploitation and outsiderdom regardless of the validity of any deeper meanings, the end result with King Kong was lightning in a bottle. It proved to be a massive hit. A true blockbuster, all the more remarkable for being released in 1933, a low point in The Great Depression. The film would be banned in newly-Nazi Germany but would prove to be a sensation in other parts of the world. Most importantly for Kong’s future, Japan where tribute and knock-off films would be made, including the officially listened by RKO silent comedy short film, Wasei King Kong (1933), starring Isamu Yamaguchi (the lead actor of Mikio Naruse’s 1931 comedy Flunky, Work Hard!). It would be screened together with King Kong, but would eventually be destroyed during WWII.

Most importantly of all, the creativity and craftsmanship on display in King Kong would spark the imaginations and creative ambitions of generations of young viewers, curious about how film could bring the impossible to life. A generation that would soon grow up and create monster movies of their own. Some would even take Kong into their own hands one day. In the meantime, intent to capitalize on the film’s runaway success, RKO would hastily green light a sequel. How could a film like King Kong even be followed up?

The Heir Apparent.

Merian C. Cooper had hoped to make a sequel that was even grander than the first film, and had David O. Selznick not moved on from RKO by the time King Kong was released, the sequel may have received a budget and schedule comparable to the first film, and the end result may have been a film that rivalled its predecessor. Instead, what RKO wanted of Cooper and his creative team was a quickie cash-in sequel. With only a fraction of the time and money that was given to the first film, Cooper, somewhat disillusioned, would end up taking a less hands-on approach. Ruth Rose, I think wisely, realizing that the sequel, with its limited resources, would be incapable of astonishing audiences in quite the same way, opted to give the sequel a more comedic tone. She quipped, “If you can’t make it bigger, make it funnier.”

Even with its more lighthearted tone, there are numerous moments obliquely referring to the strife of the Great Depression. The socio-political turmoil going on in the world at that time is felt throughout the sequel. If the first film was about some variation of themes revolving around exploitation, then this film might be described as a story about the consequences of exploitation. The story is kicked off shortly after the ending of the first film, with Carl Denham facing fallout from his actions in the form of numerous lawsuits, a Grand Jury indictment, and general disgrace. That prompts him to skip town, returning to a life at sea, eventually leading to his return to Skull Island in hopes of finding a treasure that might alleviate his financial woes. Along the way he’s joined by a young woman named Hilda (played by Helen Mack), who performs the ukulele in an act with small monkeys, and who stows away on Denham’s ship after her father was murdered by the man who sold Denham the map to Kong’s island.There’s a gentle romance with Hilda that gives the typically exploitative Denham the opportunity to care for someone in a non-transactional way. It’s enough to make you consider if Denham can change as a person, as he’s wracked with guilt and remorse over his responsibility for the events seen in the first film.

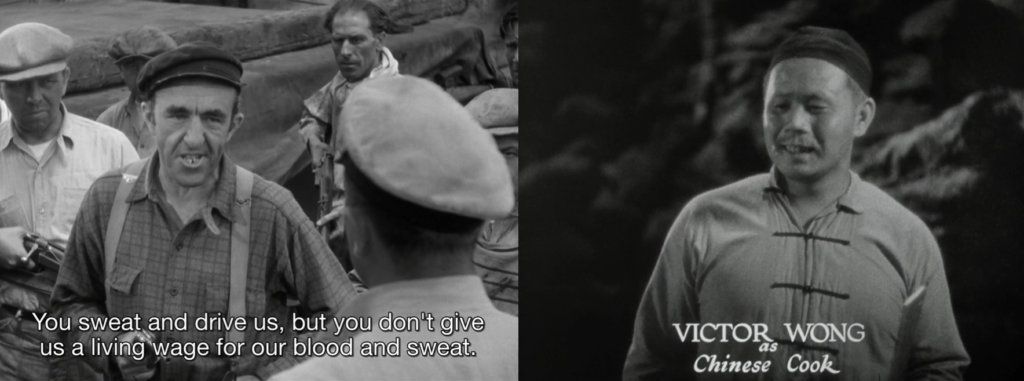

Even if the audience is ready to forgive Denham, many characters are not. At one point, the crew of Denham’s ship mutinies, something that is perhaps understandable considering that twelve of Denham’s crew died on the expedition in the previous film. The mutineers are led by a crewman known as “Red” and who spouts some not so subtle communist references. The only crewman to side against the mutineers and willingly be cast off in a dingy along with Denham, Hilda, and the captain, is one of the few supporting characters to survive Skull Island in the original film, Charlie the Chinese cook. Charlie is played by Victor Wong, and not to be confused with the Victor Wong who would act in numerous ‘80s and ‘90s genre classics that readers might be familiar with, and is a character that has often been criticised for evoking a stereotypical image of Chinese people that abounded at that time. In spite of that, I think he’s an interesting character. In particular, it’s worth considering the agency in his decision to expel himself from the ship, which comes not out of pure loyalty to Denham, but rather because he does not like the mutineers. With China then in the midst of a brutal civil war between communist and republican forces, Charlie’s line about not liking those men has a surprising amount of weight to it. It suggests a history, or a more complex inner life for a character that has often been dismissed as two dimensional.

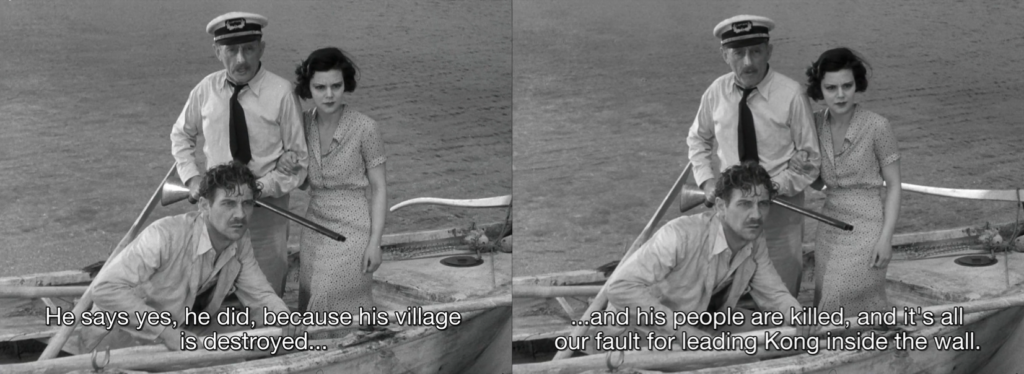

Another group that is reluctant to forgive Denham are the inhabitants of Skull Island. While the islanders do evoke uncomfortable stereotypes in line with a colonial outlook of the world, I think it’s notable that there are moments of sympathy in the original King Kong which complicate that perspective. Even though they’re only really featured in one brief scene in the sequel when Denham and his mates make their first attempt to land, it seems significant that that scene highlights the havoc brought to their world by Denham. Upon his return to Skull Island, Denham tries to win the islanders over by telling them that he killed their god-king, which goes about as well as you’d expect.

Of course the big star of the original was still dead, so how could they make a sequel anyway? Well, as it happens, Kong would have a son.

Aside from his albino appearance, at a glance, it might be easy to assume that Kong’s son is very much like his father. To bring him to life, a miniature model of his father was used, repurposed from the first film. However, the two characters are not all that similar. The most obvious physical distinction would be that Kong’s son is considerably smaller, as if he’s unable to fill his father’s shoes. That sentiment carries over into how he is characterized as well. Kong’s son is much less ferocious and intimidating than his father, and much more adorable and vulnerable. In fact, when he’s discovered by the film’s intrepid humans, he’s drowning in quicksand and needs their help to get out. He’s not quite as charismatic as his father, but he’s not entirely charmless either. Also, whenever there’s an opportunity for comedic relief, he can’t help but mug at the camera.

Through Kong’s son, Denham sees an opportunity to redeem himself for the role he played in Kong’s death. Things don’t work out that way though, and get messy before the end. An earthquake leads to a tsunami, which plunges Skull Island under water. Denham and Kong’s son climb to the very top of Kong’s old skull mountain home, but the water continues to rise. Denham is only able to survive and be rescued because Kong’s son lifts the man above the water, drowning in the process. So ultimately, it is Kong’s son who saves Denham. There’s an eerie moment of reflection that comes after Denham and his friends have been rescued, when he wonders if Kong’s son even understood that he saved his life.

In many respects, it is possible to detect that there was not the same level of passion for Son of Kong as there was for its predecessor. Perhaps most notable with the special effects. While still effective, they just don’t reflect the same attention to detail seen in the original. It would be easy to blame it on the heavily reduced time and money available, but there’s a dark shadow that hangs over the film. It was while working on the film that Willis O’Brien would suffer an immense personal tragedy. O’Brien had been divorced for three years, and his ex-wife had primary custody of their children, but he was widely regarded as a good father to his two sons, even having them visit the studio while he worked on Son of Kong, letting them examine and touch his miniatures (the younger of the two boys was blind). So, it came as a shock when his ex-wife, who had been struggling with both physical and mental health issues, shot and killed the two boys, and then unsuccessfully tried to kill herself. This emotionally devastated O’Brien, and left him despondent for the remaining time while working on the film, with his assistant often having to step in and do the work that O’Brien would normally handle. For years after, O’Brien would refuse to even discuss Son of Kong because the experience of making it was so painful. I was hesitant to include this personal tragedy, but I think it’s worth mentioning not only for its impact on one of the fathers of Kong but also to try to put into context some of the film’s shortcomings, which have often been discussed with insensitivity over the years.

Son of Kong would be released in 1933, only a few months after the first film. While it pulled in a modest profit, it didn’t wow audiences in the way that its predecessor had. It’s understandable why, though I think there are still many worthy ideas and moments as a continuation to be found in it.

Succession of Kong.

Merian C. Cooper did propose an idea for a follow-up Kong film, which would have been more of a side-quel than a sequel. It would have been set between Kong’s capture and his arrival in New York during the original film. Damaged by a typhoon, the ship is forced to stop for repairs in Indonesia, where the arrival of some monsters necessitates the release of King Kong to fight it. It would have ended with Kong’s recapture, thus leaving the continuity of the original film undisrupted. This idea would ultimately be shelved as Cooper moved on to other projects including producing a string of films for director John Ford, as well as create the historical epic disaster film, The Last Days of Pompeii (1935), which was written by Rose, co-directed by Schoedsack, and featured special effects work by O’Brien.

Even without another film, audiences eager to see Kong again wouldn’t have to wait too long for his return to the big screen. King Kong would see its first re-release of many in 1938. However, familiar audiences may have noticed that some of their favourite moments in the film were missing. In 1934, there had been a codified clampdown on the permissiveness of subject matter in Hollywood films, ending what is now known as the pre-code era. This necessitated the removal of some of the more shocking and titillating shots in King Kong. Those scenes would be considered lost for decades, until a European print was located and the film could be restored to its full impact.*2

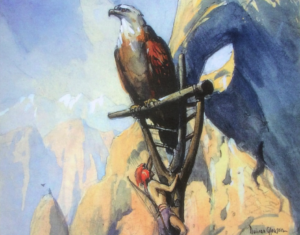

Following the success of King Kong’s re-release, Cooper and O’Brien would try to put together a new special effects-heavy film that Cooper described as “a super-western of the air.” It would have been titled War Eagles, and told a story about a disgraced WWI pilot who discovers a tribe of lost people who live alongside prehistoric animals and eagles large enough to ride. The revelation that Germany was planning to invade America sparks the hero to recruit the tribe to come to the rescue. The climax would have been a spectacular aerial battle over New York between the eagle riders and German fighter planes and a zeppelin carrying an electromagnetic pulse weapon. It would have been shot in Technicolor, a process that Cooper played a role in getting major motion pictures to adopt. It also would have been the first film for a young stop motion animator named Ray Harryhausen, who had been inspired to pursue a career in special effects by O’Brien’s work on King Kong, and had gone to work for him. I have no doubt that War Eagles would have been one of the most thrilling and technically impressive films of the era, but unfortunately, pre-production was shut down by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures for fear of its anti-Nazi message being too provocative. This was in 1939, when America largely held an isolationist stance when it came to the war that had erupted in Europe and Asia, with people who were vocally anti-Nazi often being dismissed as warmongers.

Inevitably the Second World War finally reached America. When it did, Cooper would re-enlist in the American Army Air Corps. He served in a number of different positions during the war, perhaps most notably as the chief of staff for an American volunteer air force group that would attempt to defend China from an invading Japan.

After the war, Cooper set about making a gentler ape film, one that wouldn’t fall directly into Kong’s franchise but is rightly considered to be something of a sibling film. It certainly warrants a mention when looking at the history of Kong. That film would be Mighty Joe Young (1949).

Mighty Joe Young would reunite Cooper, Schoedsack, Rose, and O’Brien one final time. Schoedsack had suffered a debilitating eye injury while testing aerial photography equipment for the American military during WWII, and was left nearly blind, so this would be his final film as a director. I think Schoedsack and Cooper’s creative reunion is a true testament to their friendship. The film would also see the return of Robert Armstrong, who plays a character named Max O’Hara, who comes across as a more sympathetic reworking of Armstrong’s previous performance as Carl Denham. It’s perhaps no surprise that Mighty Joe Young feels very much like the old band getting back together to play a new rendition of a familiar song.

The plot is kicked off by Jill Young, the daughter of a white farmer in colonial Africa, who, as a child, trades a few valuable possessions with a pair of poachers for an orphaned baby gorilla. She names the gorilla Joe. Twelve years later, a wealthy showbiz man named Max O’Hara and his cowboy associate, Gregg Johnson (Ben Johnson), travel from New York to Africa to obtain lions for a new safari-themed nightclub he’s opening in Hollywood. They’re interrupted by Joe, who has grown to a giant-sized twelve feet tall (tiny compared to Kong, but still giant by gorilla standards). They decide to try to capture the unique animal, in a memorable sequence pitting cowboys with lassos against the giant ape, but it doesn’t go so well for them. Fortunately, Jill, now all grown up and played by Terry Moore, shows up to calm Joe down. Seeing Jill’s special bond and ability to communicate with Joe, Max offers her a contract to perform with Joe at the Hollywood nightclub, and pressures her to sign it. With her father having recently passed away, and wowed by his promise of fame, she agrees to his contract.

Jill and Joe’s nightclub act ends up being a big hit, but being forced to perform and kept caged up at night leaves Joe deeply unhappy. Jill also becomes quickly disillusioned with the pressures of being a celebrity. Gregg convinces her to try to get out of her contract, but Max, not wanting to lose his successful act, manages to deflect her concerns. The show goes on and becomes increasingly degrading for both Jill and Joe. After one of their performances, three drunk men sneak back to Joe’s cage and one of them ends up deliberately burning Joe’s hand with a lighter. The provoked giant gorilla goes into a rage, breaking out of his cage and rampaging about the nightclub, where panicking patrons only make things worse. Max and Gregg manage to stall police eager to shoot Joe, and Jill is able to return him to his cage, but the ape’s outburst will have terrible repercussions.

A judge orders that Joe must be killed, and several police are sent to ensure that it’s done. The situation seems hopeless, but Max, taking responsibility for bringing it about, comes up with a plan to spring Joe. He fakes a heart attack to distract the police, while Jill gets Joe from his cage and brings him to a moving van driven by Gregg. A tense chase ensues, with the police getting ever closer to shooting Joe. However, Gregg and Jill are abruptly halted when they come across a burning orphanage with children trapped on an upper floor. I’ve seen it often commented on that this turn is a little too out of left field for the film’s climax, but I think it makes thematic sense, considering that Joe is an orphan in his own right. Jill rushes into the burning building, and with the help of Joe and Gregg, are able to bring two of them down, but one small child is still left atop the quickly collapsing building. The police arrive just in time to see Joe heroically climb up and bring the child down, and then shield her from the collapsing house. As Max says, “There’s nobody in the world gonna shoot Joe now.”

The film finishes with an epilogue where Max returns to New York and shoots down a suggestion to use monkeys in an upcoming act, implying that he’s retired from using animals in his acts. He’s surprised to receive a silent 16mm movie sent by Jill, who has returned to Africa, and Gregg who’s joined her. Joe is also there, having recovered from his injuries. They all look happy, and Max adds, “They’re back home, where they belong.” The film ends with the trio waving at the audience, a big departure from the tragic ending of King Kong.

While I do wonder if this difficulty with censorship in King Kong’s re-release may have led to the creation of a loose remake of King Kong for a more artistically restrictive era, it does come across as a very sincere film and some form of collective healing experience. Maybe even an apology; if not for Kong, then certainly an apology to gorillas. The first gorilla wouldn’t be born in captivity until about seven years after the release of Mighty Joe Young, but it does reflect a shift in the pop culture perception of gorillas from dangerous half-human monsters to gentle animals closely related to us. Joe Young might be what you’d get if you took the monster out of Kong. That goes for both his appearance and his characterization. For example, Joe Young’s relationship is very explicitly a brotherly relationship with the film’s leading lady, bereft of any of the sexual undertones in Kong’s fascination with Ann Darrow. The film also takes great care to emphasize that Joe isn’t naturally aggressive, and only potentially dangerous when provoked by humans.

Mighty Joe Young also expands on King Kong’s themes of exploitation and entertainment, by highlighting the ethical dubiousness of using an intelligent animal for entertainment. I think this is a concept that’s more widely accepted today, with documentaries like Black Fish (2013) putting a spotlight on this particular issue, but it seems like a pretty remarkable stance for a film to have in 1949. Through the film’s stop motion special effects, it tries to present an ethical alternative to using real animals (though the film does make use of some real animals in several instances), and perhaps that can be appreciated more now that computer generated imagery has allowed so many films to forgo the use of trained animals. Of course, the film doesn’t seem to regard show business’ treatment of humans as being much better. It’s hard not to get the sense that Merian Cooper was perhaps someone who loved filmmaking and all the artistic possibilities it presented, but hated the restrictive systems built around it.

Mighty Joe Young would prove to be a mild disappointment at the box office. Maybe audiences just didn’t want to see a film about a friendly gorilla who lives at the end. Who knows? Regardless, the film would become incredibly beloved and held in high regard, with many aficionados considering it to be a superior film to King Kong. It’s also widely recognized as Willis O’Brien’s special effects masterwork, representing the culmination of his dedication to and innovation with the craft of stop motion animation. It would also represent an important early milestone in the career of O’Brien’s protégée Ray Harryhausen, who worked as his assistant on the film.

The fourth re-release of King Kong in 1952 would gross nearly as much as Mighty Joe Young. Not only did it prove Kong’s enduring popularity, it also brought about a new wave of giant monster movies. Two decades after it debuted, the generation of artists who had been inspired by King Kong were now making films of their own, often incorporating concerns about the new atomic age brought about by the invention of nuclear bombs. Their work might be considered the illegitimate sons of Kong, but it’s often more interesting and powerful than Son of Kong.

One of the most notable of this new wave of monster movies would be The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), which is about a nuclear test unleashing a dinosaur that had been frozen in ice which promptly goes on a rampage, leading it to New York. It would be Harryhausen’s first film where he’d be in charge of the special effects. It was also based on a story by science fiction author Ray Bradbury, who had also been greatly impacted by seeing King Kong when he was a boy.

Of the many giant monster films to emerge at that time, one stands out above all the others, Godzilla (1954). It would take inspiration from both King Kong and The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms. In fact, the proper name of Godzilla, “Gojira” (ゴジラ) is a mish-mash of “gorilla” and “kurira” (whale), a tip-off to the mutated dinosaur’s unlikely ape origin.

Godzilla tells a somewhat familiar story of a semi-aquatic dinosaur who has been awakened and irradiated by nuclear testing. Godzilla goes on a rampage that brings it to Tokyo, where the monster is completely unstoppable in its devastation, stomping and blasting radiation from its mouth. Only a newly invented device has the power to stop the creature, which presents a dilemma because it has even more destructive potential than the hydrogen bomb. The inventor of the device, the eye-patch-wearing Doctor Serizawa (played by Akihiko Hirata) ultimately allows it to be used to kill Godzilla, but sacrifices himself in the process to ensure that his invention would never be made again.

Godzilla would be directed by Ishiro Honda, who had developed a strong reputation as an assistant director well-known for collaborating with the renowned director Akira Kurosawa, something that would continue even after Honda made the jump to directing films of his own. Honda had a reputation for a high standard of professionalism, but also for a gentleness in his direction. He was very nearly universally beloved, and would find his improbable calling in making movies about monsters. Honda would famously say, “Monsters are tragic beings. They are born too tall, too strong, too heavy. They are not evil by choice. That is their tragedy.” He’d also contribute to the script, working with Takeo Murata and drawing on real-life nuclear tragedy to instil his giant monster movie an earned sombreness and emotional weight. While atomic age anxieties were ubiquitous in the monster movies of the 1950s, Japan had a uniquely tragic relationship with the horrors of nuclear power. There were of course the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki which brought an end to the Second World War, but also in 1954 the crew of a Japanese fishing boat, the Lucky Dragon Number 5, would unwittingly be poisoned by irradiated ash. It was fallout of an American nuclear bomb test detonation on the Bikini Atoll. With these events in mind, Honda held artistic goals that extended beyond simply thrilling an audience.

The special effects for Godzilla were created by Eiji Tsuburaya, who was already in his thirties when he saw King Kong for the first time in 1933, but was so taken by it that once the film had finished, he immediately went straight home to excitedly tell his wife that he would pursue a career in special effects. Tsuburaya found a niche for himself doing miniature and compositing work for war movies, but his real passion was for monsters. Inspired by Willis O’Brien and Ray Harryhausen, Tsuburaya initially wanted to use stop motion animation entirely for Godzilla’s effects. However, with his restrictive budget, Tsuburaya calculated that to use stop motion animation for the entire film would take seven years rather than the seven months he had available, so he resorted to using a performer in a rubber suit for most of the monster’s scenes. This approach would ultimately earn Godzilla the disdain of Harryhausen, who viewed it as tawdry. I think the effectiveness of the 100 kilogram suit and the personality of the man inside are not to be disregarded though. The suit performer Haruo Nakajima, was an actor whom Honda had taken a liking to while meeting him on the war film, Eagle of the Pacific (1953) where Nakajima had volunteered to let himself be set on fire for a scene. His performance turned the constrained movements of the rubber suit into a positive, giving the slow-moving monster a sense of power and anguish, which together with camera techniques like slow motion would create the impression of a monster that distinguished itself from its immediate peers. It’s a technique that has been dubbed “suitmation,” something that would become a stylistic standard for what is known as the Tokusatsu (“special effects”) genre.

Godzilla would prove to be as emotionally compelling as it was entertaining, connecting with audiences in a profound way. It raised the bar for monster movies. The giant irradiated mutant dinosaur Godzilla stood out as a potent embodiment of both victimizer and victim, with its rampage brought about from a place of deep suffering. Much like King Kong, it wouldn’t be unusual to hear of people crying when Godzilla, despite all the carnage he caused, is killed at the end of the film. Both as a monster, and as an artistic creation, Godzilla would rival King Kong and finally offer a worthy successor.

Godzilla would be re-edited with new footage and dubbed into English for a somewhat less impactful, but still entertaining American release, where it would prove to be a surprise hit. The American version would be titled Godzilla, King of the Monsters, almost as if Kong’s crown had been usurped.

To Be Continued in Part 2…

*1 – A Note on The King Kong Screenplay.

Cooper initially arranged for the script to be assigned to Edgar Wallace, an English novelist famous for his thrillers and detective stories. His background as a journalist who travelled to the Congo Free State to expose the horrific atrocities committed under Belgian King Leopold II’s rule, made him an ideal choice to shape Cooper’s story into a dark and compelling narrative. Wallace managed to crank out the first draft of what would become King Kong (then called The Beast) in only four days. Doubtless Wallace would have contributed more than that, had he not contracted pneumonia, which would be complicated by his diabetes, and after disregarding Cooper’s suggestion to go to the hospital, died suddenly two weeks before the first effects scenes were to begin filming.

Writing duties then went to James A. Creelman, who was already working with Cooper on the screenplay for The Most Dangerous Game (and who, incidentally, in 1941 would commit suicide by jumping 18 stories from the roof of a building in Manhattan). The script that Creelman created has the basic structure of the story in place, but there are some notable differences from the final film, like Kong’s island being uninhabited by people, or Kong being displayed in shackles in Yankee Stadium rather than in a Broadway theatre.

Creelman’s writing was notoriously flowery and left a few plot holes and awkward exposition, and he was pressed to finish the script for The Most Dangerous Game, so former journalist Horace McCoy (who would later go on to be a successful novelist, writing They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? in 1935) was brought in to make revisions. This would result in a draft that was pretty close to the final film.

Interestingly, one piece of the story would even come from an actor, Steve Clemento (who was born Esteban Clemento Morro, and would later go by Steve Clemente), who would appear in The Most Dangerous Game in addition to playing one of the islanders in King Kong. Drawing on a personal experience, he would contribute to a sequence early in the film where Carl Denham calculatedly singles out Ann Darrow as a vulnerable woman he can recruit for his expedition film, and she initially reacts to him with cautious skepticism but is ultimately too desperate to rebuff him.

The final writer brought in to tighten and liven everything up would be Ruth Rose, whose life is discussed more in depth in the main body of this article. One extra tidbit though; she would would also construct a language for the natives of Kong’s island, drawing inspiration from the Nias language spoken by the people of an island off the coast of Sumatra.

*2 – A Note on The Lost Spider Pit Scene.

The most famous lost scene, perhaps not just for King Kong, but maybe any film, is the “spider pit” sequence. It was supposedly removed not for content but rather for pacing reasons after an early screening of the film in 1933, though it certainly left an impression on the shocked younger viewers who saw it. The scene took place after Kong shakes the ship’s crew off and into a pit filled with giant, deadly spiders, insects, and reptiles that quickly chomp on the crew.

The footage for the scene was lost (and most likely destroyed), and it took on an almost mythic status. Actually, until a few still photographs from the scene were discovered in the 1990s, it was debated if the scene even existed at all.

Peter Jackson create a lovingly crafted approximation of the lost scene that’s included on the Blu-Ray release of 1933’s King Kong, using many of the original techniques that would have been used to create it in the first place. Jackson would also do his own grisly version of the scene for his 2005 remake of King Kong. If it’s true that the original scene was indeed removed for pacing reasons, that just might say something about Jackson’s film including it.