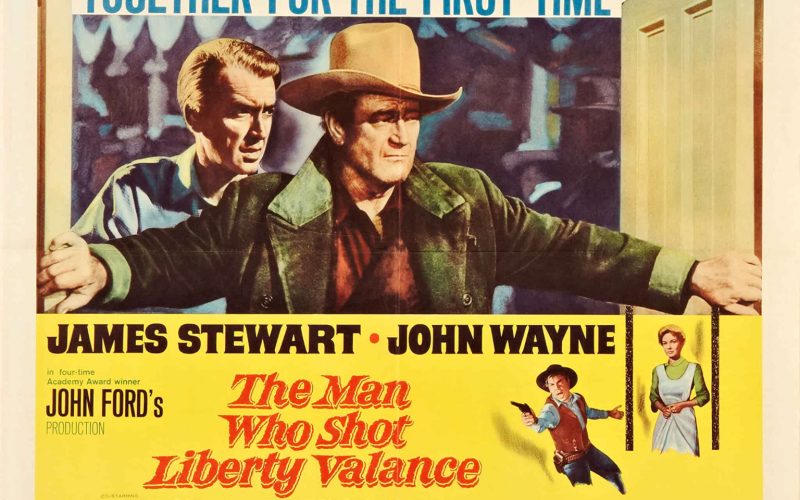

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962).

There are, very broadly, two types of Western which, for reasons that will become obvious, can be labelled as a Cactus Rose or a Garden Rose. The first are those films that are set before the taming of the West, films like Red River, How the West Was Won and The Searchers. These films are often set in the wide-open landscapes of Texas, Arizona or New Mexico, and feature rugged men sleeping beneath the stars, battling Indians and outlaws, with the goal of finding somewhere to settle down and grow old.

The second type takes place in towns. The West may not have been won entirely but it had been subdued. The focus is not on the open landscapes but on the wide streets of Dodge City, Tombstone or Santa Fe. The milieu for these Westerns is the saloon, the jailhouse and, more often than not, the undertakers. The hero doesn’t battle Indians, he battles gunslingers, desperados, hired killers and those out to make a name for themselves. These films include The Gunfighter, High Noon, Destry Rides Again and Rio Bravo.

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance is primarily an example of the second type of Western, however, it also chronicles an important time in American history: when people of the towns, with their increasing populations, became a power and began voting for Statehood and full membership of the United States. In many cases, this was violently opposed by the cattle bosses who owned vast areas of land, land acquired by simply being there first and being more ruthless with a gun (see Howard Hawk’s Red River).

The cattlemen are represented by Liberty Valance (Lee Marvin), leader of a group of outlaws hired to bully the residents of Shinbone into remaining a territory and therefore maintaining the cattlemen’s power. Valance survives by creating fear. This is his currency and he knows that as long as he can maintain this fear, he’s untouchable. No one will face off against him. This is the power of the cattle barons. They confront democracy with fear, thus controlling any form of dissent.

The film is told in flashback. At the beginning, Senator Ransom “Ranse” Stoddard (James Stewart) and his wife Hallie (Vera Miles), arrive at Shinbone. They are treated with reverence by the townspeople and soon the press are sniffing for an interview. What especially perplexes the editor of the Shinbone Star is why this important man would come all the way to this frontier town, with no fanfare, to attend the funeral of someone he has never heard of. Ranse agrees to their request as he has something to get off his chest.

As a young man, Ranse was greeted on his arrival to Shinbone by gunpoint. On the other end of the gun was Liberty Valance, who robs the stagecoach Ranse is travelling on. The young lawyer is left beaten, penniless and bruised and is taken in by Tom Doniphan (John Wayne) who puts him into the care of restaurant owner Ericson (John Qualen), his wife Nora (Jeanette Nolan), and employee Hallie. They tend to his wounds and, to earn his keep, Ranse starts working as a dishwasher. Later he sets out to teach Hallie, and others in the town, how to read and write.

Hallie represents a typical woman in these times. She is tough, hardworking and illiterate; she also represents the civilising of the west. At the start of the film she is widely seen as Doniphan’s girl (although he hasn’t asked her out yet) but as the film progresses, she slowly falls for Ranse – she leaves the desert for the garden.

Throughout the film there are references to the taming of the West and one motif is more apparent than others – the rose. Early in the film, Doniphan gives Hallie a Cactus rose, a symbol of the desert. Ranse however entices her with the promise that one day he will show her a real rose, a symbol of the garden. This is what The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance is about, that moment when the desert becomes a garden, when civilisation overcomes lawlessness, when Ranse’s law books become more powerful than the gun.

It is the gun however that is decisive. Valance calls out Ranse and there‘s a shootout in the street. The result seems like a foregone conclusion, yet miraculously, Valance is shot and dies in the very streets that despise him. Ordinarily this would be the end of the film but it’s not. Doniphan realises the feelings Hallie has for Ranse moments after Valance is killed. Civilisation has won and Doniphan – the symbol of the old rugged west – is no longer relevant. He knows this immediately.

The ending of the film reconfirms the role of the gun in the winning of the West, but it is not a story that can really be told. As Ranse finishes his story, there is a realisation that the myths of the West are sometimes more important than the facts. Although America was civilised, the myth of how it was achieved still holds dear in the hearts of every American. This is as true today as it was in 1962 when the film was made; it is very much the essence of Americanism and is summed up with the famous quote;

‘When the legend becomes fact, print the legend!’

Of course, the reason The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance works is because it is not just a great western but a great film, full to the brim with wonderful performances with Stewart, Wayne and Miles excelling as the leads. However, as is often the case in films like this, it is the support that raises it to something special. Edmond O’Brien is wonderful as the founder of the Shinbone Star, Dutton Peabody; Andy Devine plays the cowardly Marshal Link Appleyard with relish and humour and Lee Marvin is truly menacing as the bully of the title. In addition, we have that icon of the western Lee Van Cleef as Valance’s gang member Reese, and John Carradine vocalises beautifully as the spokesman for the cattle barons.

Some people will be put off but the emphasis on dialogue over gunshots. This is not an action western – it is a drama, an important story that tells of one of the great transitions in American history. How ultimately the West won by the bullet but conquered by the ballot. It’s not an epic in the traditional sense of moviemaking, but it is in the scope of its ambitions. For me, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, is one of the great westerns, and in being so, it is also one of the great films of all time.

Film ‘89 Verdict – 10/10