Rashomon (1950) – Akira Kurosawa & the language of Japanese Cinema.

A long time ago during those first flourishes of cinephilia that would consume my life, I made it my duty to watch as many films as I could. I wanted to experience movies from all parts of the world, all corners of the earth.

The first flourishes of this obsession with movies were fed and watered by America, specifically Hollywood, but soon films from other parts of the world would make themselves known to me and my pallet expanded. I discovered the various new waves of filmmaking that seemed to pop up occasionally and all those new and exotic names that now seem as familiar to me. Names like Rossilini, Truffaut, Godard, De Sica and Almodóvar, names that have continued to pop up over and over again as my appreciation of movies continued to grow.

But there were two names which seemed, at least to my limited experienced imagination, more strange and peculiar than all the others, Yasujiro Ozu and Akira Kurosawa. Maybe it was because many of the other behemoths of cinema came from the relative proximity of France, Italy and Spain; European cousins who were unusual in language yet possessed a sameness which was easy to identify with, whereas Japan was thousands of miles away with a very singular culture and history. Or, and this is I think more likely, it was because they just made wonderful movies.

Both Ozu and Kurosawa examine the minutiae of Japanese culture that was both peculiar and universal. I think that this was because the themes, whilst specific in their use of Japanese cultural norms, were also relatable to the outside world as well. We might not understand the significance of the tatami shot used so frequently by Ozu in Tokyo Story (and all his other films) but we do understand the emotions that the film explores, disappointment, grief and loss.

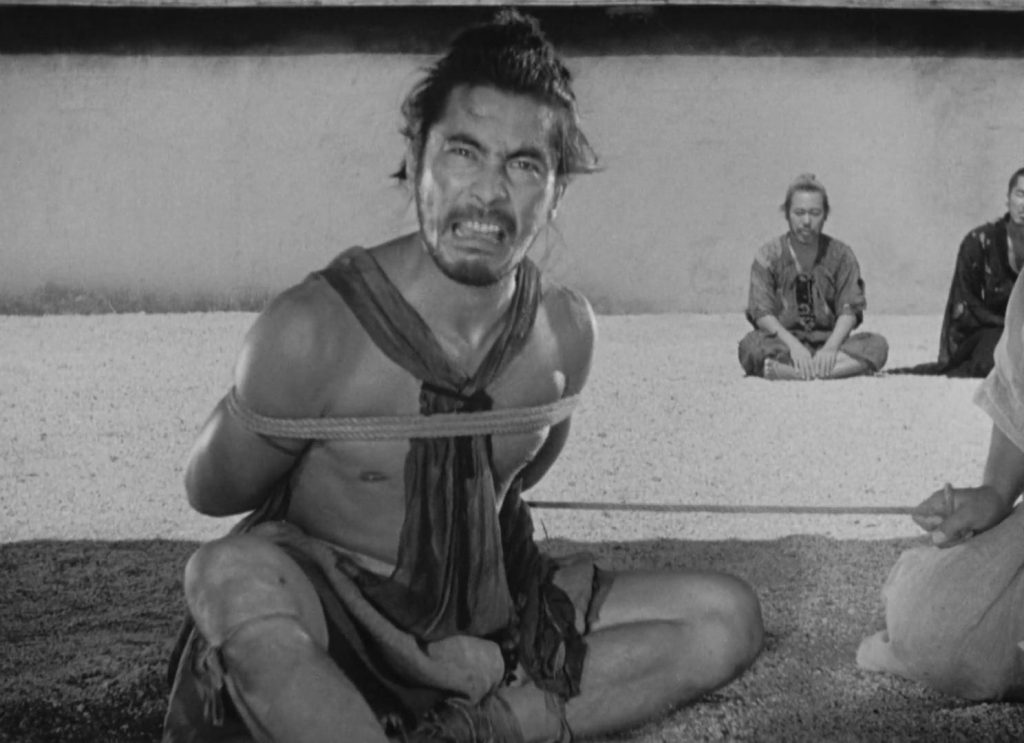

The same can be said of Kurosawa. A samurai may look particularly strange to western eyes, the histrionics of the great Toshiro Mifune may bring a smile to your face when you first see them, but you can’t help but be moved by the plight of the villagers in Seven Samurai or the hopelessness of those trapped between two warring factions in Yojimbo.

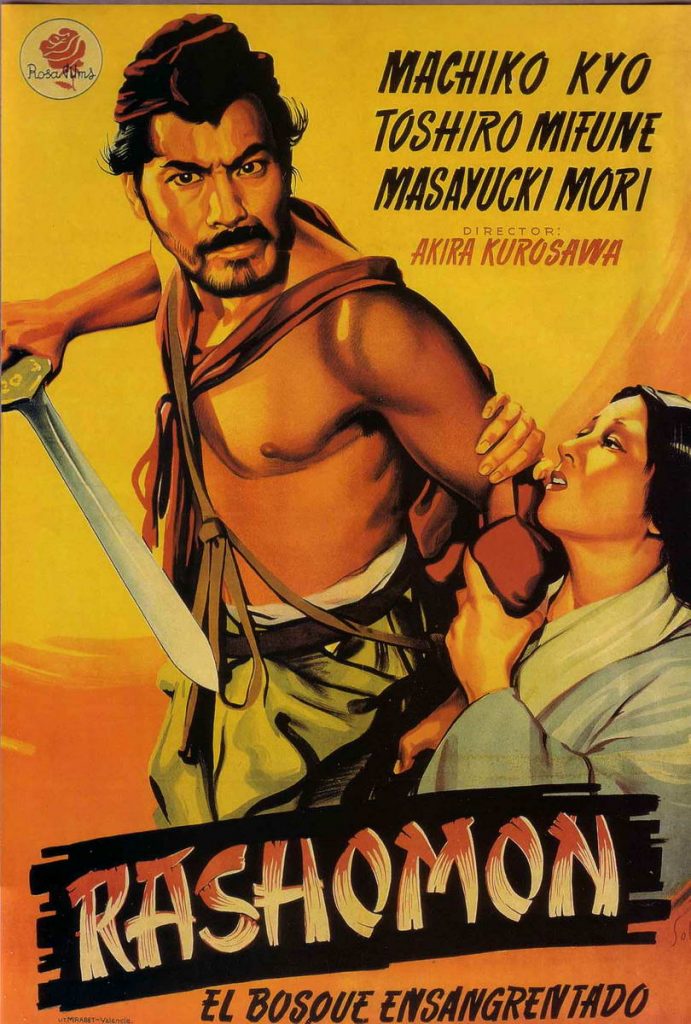

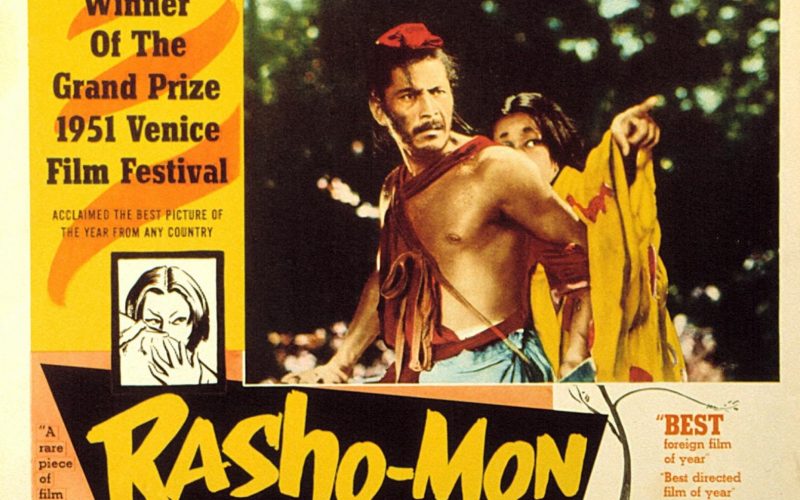

One of those films I saw during this blossoming of my filmic adulthood was Kurosawa’s (and Japan’s) first real international success – Rashomon. If there is one film that proves the point that I have been trying to make, then this is the film. Rashomon is the story of a murder, or more specifically, the stories of a murder as the details of what happened change ever so slightly with each telling.

The stories are told by a Woodcutter, a Priest, a Wife, a Bandit and even the victim himself who speaks through a medium. The facts are these: a man and his wife are travelling through a forest and are spotted by Tajomaru, a bandit well known in the area. At the end of the encounter the man is dead. Beyond that the truth becomes diluted behind a veil of lies and deceit. Afterwards the Woodcutter and the Priest take shelter from a storm beneath the ruins of the Rashomon Gate and are encouraged to tell their stories to a passerby who shelters with them

First they tell their own stories – the Woodcutter found the bodies and the Priest and was the last person to see them alive. Then they recount the versions as told by the other characters involved. Tajomaru claims he was the killer, the wife suggests that it may have been her and the ghost of the dead man claims he took his own life. These are not people lying to save their own lives as they all claim to be the murderer themselves, they are lying to hide a bigger, more fundamental and important truth. This is what drives the film and is slowly revealed through the astute questioning of the passerby.

I am not sure if I have the vocabulary to explain each person’s individual’s motives and do them justice but I’ll try. The priest is troubled by the possibility that man may harbour a deep rooted sin which he finds difficult to understand but can he be so naive? The Woodcutter wants to stay out of trouble and the only way for a westerner to fully appreciate the situation he finds himself in and the dilemma he faces in is to watch Kurosawa’s other films especially Seven Samurai which explores the desperation poor villagers live with. Of course, for a Japanese audience this would not be an issue.

The bandit’s lust is perhaps the most understandable although his later decisions regarding the woman are far more subtle as is the husband’s rejection of her. Finally, as we don’t have any back story for the man or woman, it is difficult to understand her flipping between the man she is married to and an uncouth stranger they meet on the journey. But this is where the understanding of Japanese culture derived from watching and rewatching the films of these wonderful filmmakers bears fruit and the real theme of the film becomes clear, that of honour.

Each retelling by the three principals involved in the murder acts as a way of preserving the honour of the teller; the wife doesn’t want anyone to know of her shame at rejecting her husband in favour of the bandit, the husband doesn’t want to live with the fact that his wife would reject him like that and so seppuku (suicide) is the more honourable outcome. As for the bandit, he knows that he will be paying the ultimate price for the death and doesn’t want anyone to believe he could be manipulated like he was. Of course, the truth does come out, the woodcutter saw everything but did not want to tell and because of this the priest rejects him. To the priest the woodcutter briefly represents all the lies and deceit that he has been witness to that day, but as they hear the cries of an abandoned baby, the Woodcutters unselfish attitude wins him over, restoring a little faith in humanity one more time.

Watching the films of Kurosawa, one can’t help but notice the over-exaggerated performances. Words are spat out, the characters continuously throw themselves to the ground, the fights last a long time until the characters are completely out of breath and reduced to wild lunges with their swords. The medium thrashes about, speaking with the dead man’s voice. When they are slighted characters seem to run a great distance away from the others to mope in solitude. But a Kurosawa Samurai film is not about reality, they are not depictions of real life, they have much grander themes than this.

In many respects Kurosawa and Ozu represent two sides of the same Japanese coin. Kurosawa’s grand gestures compared to Ozu’s focus on the tiniest details. But at the same time they speak to us in the same way. They may seem alien to a western audience and their language may sound strange to our ears but their words are easily translatable into our own understandings and experiences. We know what they are saying even if we speak the language. The best way to learn this language (by which I mean filmic language rather that dialect) is to watch the films of these greatest of filmmakers, to sit at the feet of these masters and consume every nuance like a dutiful student.

Whether it is in the movement of Kurosawa or the stillness of Ozu, this language is visual. Ozu began his career in silent films and Kurosawa proclaimed his appreciation for Silents on many occasions. So I implore cinephiles and would-be cinephiles wherever you are in the world to watch these films, to learn their language and I guarantee you will get a better understanding of the world, of cinema and of yourself and there’s no better place to start than with Rashomon.