The Fatty Arbuckle Trials: Hollywood’s First Great Scandal.

Every so often there is a scandal, an event featuring the rich and famous that challenges what we think we know of a particular celebrity and plunges a career and a fan base into the sludge-filled sewers of ignominy and disrepute. Often this event comes to life not only in the pages of newspapers and magazines, or even in the courts of public opinion, but in actual courts of law for the whole world to see. This phenomenon is often referred to as the ‘Trial of the Century’, often belying the fact that even though the title seems to refer to a very singular event, they do seem to come along with regularity.

From the Lindbergh Kidnapping Trial (1935), the Rosenberg espionage trials (1951), and of course, the O.J. Simpson Trial in 1995, they have brought revelation, horror, gossip and entertainment into our homes throughout the 20th and 21st centuries.

One reason there are so many candidates for Trial of the Century is simply because a hundred years is a long time and generations come and pass within that period. Because of this, it is perhaps easy to forget a possible first candidate for this inauspicious title – the Fatty Arbuckle Trials of 1921 & ‘22.

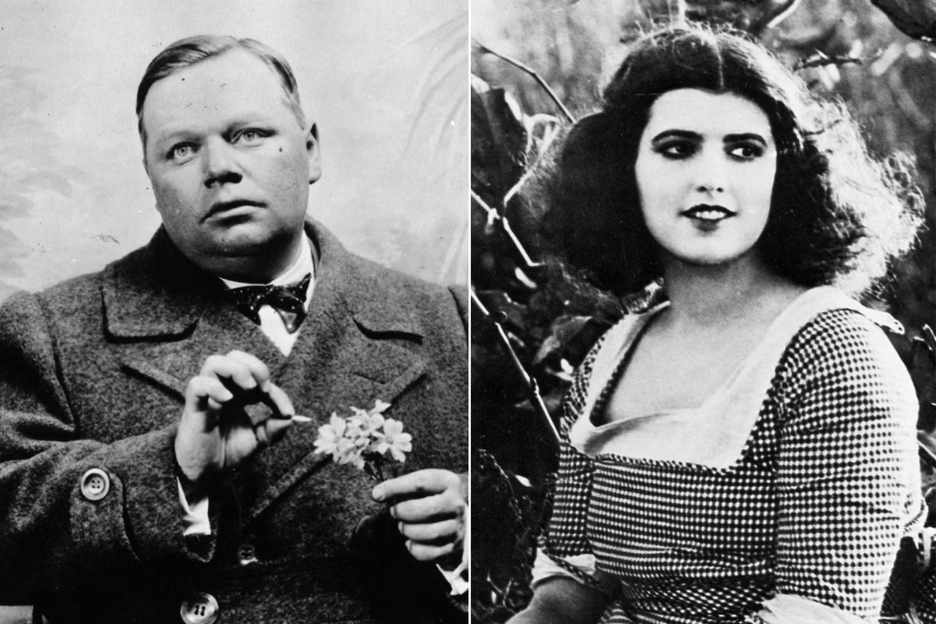

One of the first truly successful genres of cinema was slapstick comedy, that brand of physical comedy that relied on chases, pratfalls and the occasional custard pie in the face. It was a hugely popular recipe. By the 1910’s the first titans of film history were emerging and many made their name by making people laugh. Today we remember the names of Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd with loving affection. Chaplin is so famous that many who have never seen his films, can imitate his distinctive walk and describe this peculiar moustache and clothing. But there is one star of the 1910s that today is mostly forgotten. He was a genius who worked alongside Keaton, often stealing the show. He was a large man (which was unusual for the time) who wasn’t afraid to make fun of himself in a way that made him endearing to audiences. Because of his size, he was known simply as ‘Fatty’.

In the early decades of American cinema, few comedians were as beloved or as influential as Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle. With his remarkable agility despite his large frame, and his gift for slapstick, Arbuckle became a household name and one of the highest-paid actors of the silent film era. At the height of his career in 1921, he signed a contract with Paramount Pictures worth an eye-watering $1,000,000 per year. Few people would ever experience the absolute highs of celebrity, fame and wealth like Arbuckle. It was a life lived at the most dizzying heights of accomplishment and success. Yet that same year, his career and reputation were destroyed in what became one of the most notorious scandals in Hollywood history.

A little about the big man.

Roscoe Arbuckle was born in Kansas in 1887 and grew up in California, where he displayed both a natural gift for physical comedy and an extraordinary lightness on his feet despite his size. He entered vaudeville as a teenager and quickly made a name for himself through his acrobatic pratfalls and improvisational style. By 1909, Arbuckle began working in the fledgling motion picture industry, joining the Selig Polyscope Company (founded by William Selig who, unrelated but interestingly, was the first man to bring The Wizard Of Oz to the screen in 1910) and later Universal before finding his home at Keystone Studios.

At Keystone, Arbuckle became a central figure in Mack Sennett’s famous stock company of comedians. He excelled in slapstick, often playing the bumbling everyman who somehow triumphed through chaos. His portly figure became his comedic trademark, but audiences were charmed by the surprising grace with which he performed stunts, including falls, chases, and dances. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Arbuckle avoided cruelty in his comedy, cultivating a gentler and more playful screen persona. Also, unlike many of his contemporaries, he didn’t try to achieve a unique look. His sheer bulk was his personality, and he often played this up by dressing up as schoolgirls with flowing blonde hair and cutesy costumes. Miraculously, the other characters around him rarely seemed to notice anything odd. Arbuckle also helped shape the careers of other major stars. He was an early mentor to Charlie Chaplin, who claimed Arbuckle taught him the fundamentals of screen comedy. They worked together in three films.

By the late 1910s, Arbuckle was a genuine star. He signed with Paramount Pictures, where his films consistently drew large audiences and, with them, substantial profits. In 1919, he directed and starred in a number of films including Back Stage which also starred Al St. John and Buster Keaton. It also features the underappreciated actor (and later Production Manager) Charles A. Post.

Things seemed to be going very well for Roscoe Arbuckle. He was at the height of his fame and power. With it came money. With his new $1,000,000 contract from Paramount, it seemed that the sky was the limit for the big man. But if there was ever a target for a truly massive fall from grace, it was Arbuckle. Many quarters of society and influence in America were disgusted by the wealth and excess of the Hollywood crowd. Hollywood didn’t live up, nor did it portray, the high moral standards of the puritanical Christian evangelicals. There was also a level of disgust in many quarters brought on from the aristocratic belief that ‘new money’ was vulgar. Add to this the overwhelming influence that Hollywood was developing over the masses – influences that seemed determined to be immoral – and you’d get a recipe for anger and the desire to bring these upstarts in California down hard. The vanguard of this fight back was the press, especially one man – William Randolph Hearst.

William Randolph Hearst (1863–1951) was a powerful American newspaper publisher and media magnate whose controversial but very profitable tactics profoundly shaped modern journalism. Born in San Francisco to a wealthy family, Hearst inherited the San Francisco Examiner from his father in 1887 and quickly transformed it using sensationalist techniques that would become known as yellow journalism. His style emphasized bold headlines, scandal, and human-interest stories, often prioritizing drama over accuracy.

Hearst expanded aggressively, acquiring the New York Journal and eventually building the largest newspaper chain in the U.S., with nearly 30 papers at its peak. His empire also included magazines like Cosmopolitan and Good Housekeeping, and he ventured into radio and film. At one point, nearly one in four Americans read a Hearst publication.

Hearst’s legacy is complex, he revolutionised media, influenced public opinion, and built a vast empire, but also blurred the lines between journalism and propaganda. His life inspired the character of Charles Foster Kane in Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane.

The press bomb was ready – all they needed was a spark to blow it all up. And what could be better than a sex scandal featuring one of the highest paid actors of the time?

The scandal erupted over the events of September 5, 1921, when Arbuckle hosted a party at the St. Francis Hotel, San Francisco. The gathering, fueled by bootleg liquor despite the Prohibition laws of the time, drew a number of Hollywood acquaintances, among them an aspiring actress named Virginia Rappe. Three rooms were checked into – 1219, 1220 & 1221. Room 1219 was supposedly for Arbuckle and his friend Fred Fishback (who later changed his name to Fred Hibbard after the scandal). The other rooms were to be used to house other guests and as the location for the party.

It was during the party that Rappe was discovered seriously ill. She was examined by the hotel doctor, who, dismissing her symptoms as drunkenness, prescribed morphine to calm her down. This didn’t help and two days later she was taken to hospital. She died Friday 9th September 1921 from peritonitis caused by a ruptured bladder. It was discovered that Rappe suffered from chronic urinary tract infections a condition that alcohol can irritate dramatically.

Almost immediately, rumors began to spread about what had happened in Arbuckle’s hotel suite. A fellow guest, Bambina Maude Delmont, accused Arbuckle of sexually assaulting Rappe, claiming that his actions had caused her fatal injuries. She claimed that she had heard screams coming from room 1219 and had banged the door, demanding to be let in. When she finally managed to get in, she saw Arbuckle standing in the middle of the room wearing Rappe’s hat. Rappe was writhing in pain, her clothes shredded and saying, “He hurt me, he did it.”

The coroner, Dr Shelby Strange, stated that there were bruises on Rappe’s arms and that the ruptured bladder was caused by “external violence.” The press seized upon this story with sensational headlines, portraying Arbuckle as a monstrous figure who, whilst sexually assaulting Rappe, had crushed her under his enormous weight. William Randolph Hearst claimed that Fatty Arbuckle sold more newspapers for him than the sinking of the Lusitania.

The press had a perfect villain, a man whose sheer body size was a reminder of Hollywood excess, and decadent luxury. In a time when the average American was slim, an obese man was the perfect representation of all that was wrong with Hollywood. John Roach Straton, a preacher at Calvary Baptist Church in New York City, which was the first church to operate its own radio station, conducted a sermon on Arbuckle and the “sin-steeped” industry in which he was employed.

Whilst some theaters continued to show Arbuckle’s films to appease the public’s insatiable morbid curiosity, most pulled the films immediately.

Arbuckle claimed innocence. In a note to his friend, producer and second president of United Artists, Joseph Schenck, he said; “When something happens in half an hour that will change a man’s whole life, it’s pretty tough especially when a person is absolutely innocent in deed, word or thought of any wrong.”

What followed were three trials which, ultimately, failed to prove that Arbuckle had anything to do with Rappe’s death. Yet the true trials did not happen in the courthouse, it happened in the newspapers. And they weren’t going to let a little thing like facts get in the way of a good story and a moral crusade, especially if it sold newspapers.

The Trials.

The first trial began on November 14th, 1921 in San Francisco. Arbuckle had always been a man who spent just about every penny he had as soon as he had it, so he could not afford a defence. The funding for the trials came from Joseph Schenck, who promised to pay for everything in the hope that an acquittal would see this money-making machine back in front of the camera in no time. They hired Gavin McNab as their lead defence counsel and the prosecutor was San Francisco district attorney Matthew Brady.

According to Kevin Brownlow in his book, The Parade Goes By, Arbuckle’s wife, Minta Durfee, who chose to stand by her husband’s side (at least for the time being – they divorced in 1925) was shot at as she entered the courtroom. This just illustrates how febrile the atmosphere was at the time.

The prosecution’s case was quite simple and rested largely on the testimony of Bambina Maude Delmont, who claimed that Arbuckle had attacked Rappe in his bedroom. However, despite being lauded in the press, Delmont’s credibility was deeply compromised, she had a history of extortion and blackmail, and her story was riddled with inconsistencies. In the end, prosecutors ultimately chose not to call her as a witness, fearing she would destroy their case. Instead they relied on circumstantial evidence and testimony from other guests, many of whom admitted they had been drinking heavily and could recall events only vaguely. One example is model Betty Campbell, who attended the party and testified that she saw Arbuckle with a smile on his face hours after the alleged rape occurred. However, during cross-examination, Campbell revealed that Brady had threatened to charge her with perjury if she did not testify against Arbuckle.

The defence argued that Rappe’s death was due to preexisting medical conditions, noting that she had suffered from chronic bladder problems. Arbuckle himself testified, denying any assault and insisting that he had merely tried to help Rappe after she became ill.

The defence always had an uphill battle, especially as one of their members, Helen Hubbard, whose husband had ties with the District Attorney’s department, refused to examine the exhibits or read the trial transcripts during deliberations. She was convinced that Arbuckle was guilty, and nothing could dissuade her of this notion.

Other Jury members were more open-minded and some stated that, whilst they thought it was a good chance that Arbuckle was guilty, there was still a high level of reasonable doubt, and so had no choice but to give a not-guilty verdict. The jury deadlocked, ten members favoured acquittal, while two pushed for conviction.

Undeterred, prosecutors retried the case, and the second trial began on January 11th 1922. This time they sought to strengthen their argument by emphasising Arbuckle’s physical size, suggesting that even without deliberate violence, his weight could have fatally injured Rappe during an assault. They introduced testimony from medical experts who claimed that trauma could have caused the rupture.

The defence countered with their own medical experts, who testified that no evidence of assault was present and that Rappe’s condition was consistent with natural causes. This time another witness from the first trial, Zey Prevon, testified that District Attorney Brady had forced her to lie. Another witness from the first trial was the security guard, Jesse Norgard, who claimed Arbuckle had asked him for a key to Rappe’s room. Norgard’s testimony soon fell apart at the witness stand when he was revealed to be an ex-convict under indictment for sexually assaulting an eight-year-old girl and was only testifying to get his sentence reduced by Brady.

Rappe’s past was also dragged up in this trial and there were accusations of promiscuity and heavy drinking. It all seemed to be going Arbuckle’s way, and the defence were so confident, they didn’t ask the star to testify this time. This proved a costly mistake as some jurors thought this was an indication of his guilt. Once again, the jury was deadlocked, this time nine jurors in favour of acquittal and three for conviction.

By the time the third and final trial began on March 13th, 1922, Arbuckle’s career was in ruin. His films were no longer playing, the newspapers continued to produce story after story of debauchery and decadence, and Fatty was no longer perceived as a lovable comic with a talent for pratfalls, but someone who took part in Hollywood orgies, committed murder and was guilty of a plethora of other perversions. His accuser, Maude Delmont, was touring the US with her one-woman show based on her involvement in the case. Her unreliability and the proof that much of what she said was fabricated, didn’t seem to matter to her paying audiences.

This time however, the defence was at its best. Rappe died of natural causes and, if anyone was to blame, it was Rappe and the lifestyle she insisted on living despite doctors telling her to stop. The defence portrayed Arbuckle not as a predator but as a man caught in a tragic accident that had been misrepresented by scandal-mongering newspapers.

On April 12th, 1922, after only six minutes of deliberation, the jury returned with a unanimous verdict of acquittal. In an extraordinary move, the jury issued a formal statement apologising to Arbuckle, declaring; “Acquittal is not enough for Roscoe Arbuckle. We feel that a great injustice has been done him. We feel also that it was only our plain duty to give him this exoneration, under the evidence, for there was not the slightest proof adduced to connect him in any way with the commission of a crime. He was manly throughout the case and told a straightforward story on the witness stand, which we all believed. The happening at the hotel was an unfortunate affair for which Arbuckle, so the evidence shows, was in no way responsible. We wish him success and hope that the American people will take the judgment of fourteen men and women who have sat listening for thirty-one days to evidence, that Roscoe Arbuckle is entirely innocent and free from all blame.”

Roscoe ‘Fatty’ Arbuckle was free at last. He had been acquitted of murder and declared free of any blame. This apology by the jury may have been extraordinary and should have been the beginning of his comeback. Unfortunately for him, whereas his legal slate may have been wiped clean, his reputation was shattered. The press cared little for the verdict. Whereas Arbuckle had provided hundreds of lurid headlines, the news of his acquittal was buried.

Six days after the trial, Will Hayes, who served as the head of the newly formed Motion Pictures Producers and Distributors of America censor board, declared that Arbuckle was an example of the moral sewage that was Hollywood, and banned the actor for life. To make things worse, one of the members of the board was Arbuckle’s friend and producer, Joseph Schenck. It was Schenck who gave him the news. For Schenck it meant that Arbuckle would never be able to pay back the money for the trial. In lieu of payment, Schenck took ownership of Arbuckle’s Tudor mansion on West Adams Boulevard near Figuero. Today, the house is owned by the archbishop of L.A. and is used to dorm seminarians.

The whole process had killed Arbuckle’s career, and slowly it was killing him too. He started to drink heavily and his health deteriorated rapidly. He took on a number of roles, and it is said that he directed a few scenes in Buster Keaton’s masterpiece, Sherlock Jr. However, with Hollywood determined to shun him, there were very few jobs available or people who would hire him. He did have his defenders, such as Photoplay’s James R. Quirk, who, in the August 1925 edition wrote: “I would like to see Roscoe Arbuckle make a comeback to the screen. The American nation prides itself upon its spirit of fair play. We like the whole world to look upon America as the place where every man gets a square deal. Are you sure Roscoe Arbuckle is getting one today? I’m not.”

Arbuckle adopted a pseudonym, Will Goodrich, and directed several unsuccessful pictures. Louise Brooks who starred in the short film, Windy Riley Goes Hollywood (1931) stated; “He made no attempt to direct this picture. He just sat in his director’s chair like a dead man. He had been very nice and sweetly dead ever since the scandal that ruined his career. But it was such an amazing thing for me to come in to make this broken-down picture, and to find my director was the great Roscoe Arbuckle. Oh, I thought he was magnificent in films. He was a wonderful dancer—a wonderful ballroom dancer, in his heyday. It was like floating in the arms of a huge doughnut—really delightful.”

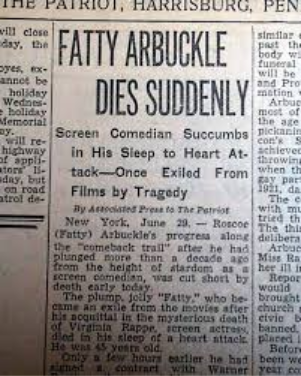

On June 29th, 1933, things finally seemed to be looking up. Arbuckle had recently completed several films and had signed a contract to direct a feature film with Warner Brothers. He was married again and was celebrating his first wedding anniversary with some friends when he was heard to say, ‘This is the best day of my life’.

That night he suffered a heart attack and died. He was just 46.

At the time of his death, he was staying at the Park Central Hotel, which was also the place where mobsters Albert Anastasia (shot in the barber shop just off the lobby) and Arnold Rothstein (shot whilst playing poker) were later murdered.

Today, Fatty Arbuckle’s legacy lives on. The films he made are still genuinely funny and entertaining. His dexterity and mobility (especially because of and despite of his size) are still remarkable. Films such as Life of the Party or The Butcher Boy, still stand out amongst the very best silent era films and comedies.

He had so much more to offer and could easily have been ranked amongst Chaplin, Keaton and Harold Lloyd as the icons of 1920’s cinema and beyond. And he should have been. His story is a tragedy, not just because of what happened to Virginia Rappe in a hotel room in San Francisco, but because it represents the tenuous and sometimes confrontational relationship between celebrity and the press. The press was more than happy to laud the stars of the silver screen when they sold papers and equally as happy to tear them down when the opportunity came along to sell more.

Arbuckle’s three trials also exposed the fragility of the justice system. The District Attorney seemed to use corrupt methods to win his case and when all this failed, it still didn’t matter. In fact, the acquittal meant nothing in the long run. Yes, Arbuckle was free from prison or the very real possibility of execution, but ultimately the newspapers won. Arbuckle wasn’t just the victim of a miscarriage of justice, he was also a victim of an orchestrated and gleeful character assassination.

In January 1922, during the second Trial, Paramount director William Desmond Taylor was murdered. It seemed to act as fuel to the accusations of immorality in Hollywood. In February 1922, Joseph Schenck wrote an open letter to the American press; “We are not rampant with vice. We are law-abiding citizens, and we rear families. And yet William Taylor’s death has resulted in aspersions being cast upon this industry, and upon us, for we are striving to make the world a better place to live in through the screen. And we, who have accepted that responsibility placed upon us by the public through their patronage, feel it a personal affront to assume through innuendo that we are not worthy of that honour.”

The letter was signed by Charlie Chaplin, Mack Sennett, Louis B. Mayer, Norma and Constance Talmadge, Ben Turpin, King Vidor and Buster Keaton. No mention was made of Roscoe Arbuckle or the attempt to kill the career of an innocent man.