Velvet Lips: Joan Crawford, Eddie Mannix and the first golden age of pornography.

It’s easy to argue today that the golden age of Hollywood is a myth. However, there was a time when that myth seemed more real to audiences. Studios like Paramount, 20th Century Fox, MGM, and Universal, studio names that still capture the imagination of cinephiles everywhere, were created at a time when the industry itself was trying to come to terms with exactly what it was, how much money was available, and how big an impact they could have on the masses who paid time and time again to sit in huge auditoriums and watch dreams become reality on a massive scale.

It was a time when the silver screen was barely hitting adolescence. From the outside everything seemed more magical, more impactful and more dreamy. From the inside however, it was sometimes very different. Yes, there was the excesses that have, over time, become public knowledge, but there are also stories which illustrate the hardships that some of the silver screen’s greatest stars had to endure before the dazzling lights of fame found them. One of these stars was the legendary Joan Crawford.

Joan Crawford was one of Hollywood’s most enduring and transformative stars. She was an actress who boldly pushed boundaries and was amply rewarded for her success. She found fame, fortune and glory, recognised both at the box office and winning ann Academy Award for her role in Mildred Pierce (1945).

Born Lucille Fay LeSueur in 1904, Crawford had a humble and disruptive upbringing, with her father leaving his family when Crawford was less than a year old. Her mother married three times, the third being Henry J. Cassin, who ran the Ramsey Opera House. It was probably here that Crawford’s dream of becoming a dancer began.

This dream almost ended when she jumped from her front porch and cut her foot on a smashed milk bottle. It took her almost eighteen months to recover fully, but recover she did, driven by a single-minded determination that she possessed throughout her life. In 1917, her stepfather went to court accused of embezzlement for which he was acquitted, although her mother and stepfather divorced soon after. This disruption was possibly the reason why Joan’s education was said to be little more than primary school level. What she did have was ambition. She started dancing as part of a chorus line for traveling revues, before joining the theatre production Innocent Eyes (1924). Ever the self-promotor, she approached Loews Theaters publicist, Nils Granlund for help in progressing her career.

Granlund secured a position for her with singer Harry Richman’s act and arranged for her to do a screen test, which he sent to producer Harry Rapf in Hollywood. The boss of Lowes Theatres, Marcus Lowe, was the owner of MGM, and soon she was signed and appearing in a number of silent films. Her first was Lady of the Night (1925) in which she was Norma Shearer’s body double.

Her name was changed after MGM’s Head of Publicity, recognising the potential in his young scarlet, decided LeSueur sounded too much like Sewer and so organsised a ‘Name The Star’ competition in Movie Weekly. It seemed she was finally going places, and the world was her oyster. She did so out of sheer grit and determination. As MGM screenwriter Frederica Sagor Maas recalled, “No one decided to make Joan Crawford a star. Joan Crawford became a star because Joan Crawford decided to become a star.” Soon she was no longer Norma Shearer’s body double, but a star in her own right. F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote;

“Joan Crawford is doubtless the best example of the flapper, the girl you see in smart night clubs, gowned to the apex of sophistication, toying iced glasses with a remote, faintly bitter expression, dancing deliciously, laughing a great deal, with wide, hurt eyes. Young things with a talent for living.”

Her own take on her on-screen personality was more succinct: “If you want the girl next door, go next door.”

All this seems to fit the rags to riches kind of story that Hollywood loves so much. It has triumph over adversity, the embodiment of the American Dream. It seems too good to be true and, according to Crawford’s brother Hal LeSueur, it was.

Admittedly, a lot of the details of this case are murky. It is a story of family feuds, blackmail and cover-ups – all, by their very nature, extremely murky areas. There are no exact dates, no proof that we can google or videos available on YouTube. It is hearsay and innuendo. These are the reasons this story is so intriguing.

In the early 1930s, Hal LeSueur, approached MGM with an accusation so dynamite that it would not only end the career of one of the studio’s biggest stars, but also, possibly bring down the studio itself. LeSueur claimed that his sister Lucille, before she had become the mega star that was Joan Crawford, had appeared in a pornographic ‘stag’ movie called Velvet Lips.

An element of film history which is often overlooked, is the early days of the pornography industry. Many claim that the first decades of the 20th century represented the first golden age of pornography rivalling the 1970s for output and popularity. The films were known as ‘Stag Films’, deriving their name from the tradition of men-only ‘stag parties’. They were not shown in movie theatres but instead were meant for private consumption. The earliest surviving stag films date from about 1915–1927. Many were made on 16mm or 35mm film stock and were silent, black-and-white. They typically lasted about 5–10 minutes and were often crudely shot. They weren’t made for their artistic merits, after all.

In the 1930s, the underground stag industry peaked during Prohibition, speakeasies often included risqué entertainment, including these films. By the mid-1930s, censorship tightened (The Hays Code, 1934), pushing such films further underground.

Although shocking when first thought of, it all does make perfect sense. It is often said that the earliest profession was prostitution and, if you combine sex and money, there will be parties who wish to profit.

In their PHD thesis, Berries Bittersweet: Visual Representations of Black Female Sexuality in Contemporary American Pornography, Ariane Renee Cruz described stag films as:

“…in a sense, a sort of ‘traveling show,’ … They were presented in private places and screened covertly at underground locations such as private homes, basements of merchants, lodges and fraternal organizations.”

Stag films were illegal under US obscenity laws. That meant they couldn’t be legally distributed, advertised, or sold, and any film lab that processed such reels risked losing its license. In addition, viewers or collectors could be fined or jailed. This created a black market, and where there’s a black market, organised crime often steps in.

When prohibition was brought in in 1920, the sale of alcohol went underground. This also presented the perfect opportunity to sell stag movies as well. Because of the nature and the legal consequences of showing pornography, evidence today is scarce. It’s claimed that up to 90% of all Hollywood films made before 1929 are lost. If legitimate movies that were released to the masses and made huge profits for the studios are now lost, what are the chances of illegal material surviving.

What we do have are documented police and FBI raids which give us a glimpse into this underground world and the reaction by the authorities. Many of the investigations and raids targeted theatre productions rather than cinemas, with some starring well known celebrities, and they do give us a glimpse at the perceived underbelly of the 1920s & ‘30s and where the moral compass of the time was pointing.

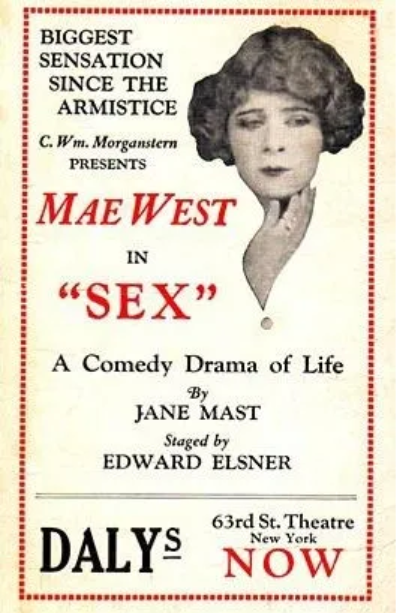

New York Vice Raids (1927–1931): In February 1927, the City of New York launched a series of raids on theatrical productions considered “immoral”. For example, three Theatre shows — The Captive, Sex and The Virgin Man — were raided and many cast and crew were arrested.

The Captive dealt with a lesbian love affair; Sex starred Mae West and addressed sexual themes, as did The Virgin Man. These actions came under the state’s anti‐obscenity laws which allowed “an entertainment … tending to the corruption of the morals of youth or others” to be prosecuted.

As part of the crackdown, the so-called ‘Wales Padlock Bill’ was passed in March 1927, allowing authorities to “padlock” theatres for indecent productions involving “sex degeneracy” or “sex perversion”. The bill was named after the Senator Benjamin A. Wales, a Republican legislator from Oneida County, New York, and directly grew out of the Mae West production Sex (another Mae West play – The Drag – about homosexuality, also fell afoul of the obscenity laws and was stopped before even opening).

Chicago Smoker Circuits: Another name for Stag Parties was ‘Smokers’ – a place where men could get together, smoke and enjoy some risqué entertainment. Chicago was one of the main hubs of the underground stag film trade in the U.S. from about 1915 through the early 1930s, with many small-time gangsters involved in the organisation of the parties. Some of the films seized by authorities were, A Free Ride (made around 1915–17) which is considered one of the earliest known American stag films; The Casting Couch (an example of how long the infamous casting couch has been going on), Getting His Goat, and The Janitor’s Daughter.

It would be no surprise, given the information we know about J. Edgar Hoover, that the FBI kept files on celebrities and the comings and goings of the Hollywood elite. It would then also be no surprise to learn that they also kept a close eye on violations to the Obscenity Laws and any possible link with the film industry. The FBI Obscenity Files were a series of reports from the 1930s–‘40s focusing on “gang distribution of obscene films and photographs.” Whilst celebrities were mentioned in these files, Elizabeth Taylor for example (lists of attempted blackmail), in the ‘30s, celebrities were often conspicuous in their absence. A possible reason for this is the power of the MGM marketing department and the influence of one man, Eddie Mannix. This brings us back to Joan Crawford and the case of the Velvet Lips.

Hal LeSueur brought the accusation to MGM as a way of blackmailing them. He claimed that in the early 1920s, his sister was so strapped for cash that she appeared in several stag films out of desperation. Admittedly there is little evidence of this today. One source comes from Crawford’s husband, Douglas Fairbanks Jr., who is quoted in a biography claiming that she told him about “a film she had made when she was in a financially desperate moment”. He said:

“Billie [her nickname] was absolutely terrified that I would find out about a film she had made … When she told me … I tried to get as many details as possible … I only got tears.”

Another commonly cited fact is that when Crawford left MGM in 1943, she purportedly wrote a personal cheque for $50,000 to the studio. Some claim this was repayment for “hush money” and the studio’s outlay in suppressing the film. The 2017 TV series, Feud: Bette and Joan (Episode 6: “Hagsploitation”) dramatized this story, presenting Velvet Lips as a stag film featuring the young Crawford, with her brother shopping it around and gossip columnist Hedda Hopper about to publish it. If this is all true, the obvious question is why no real physical evidence exists today.

Whenever you have an industry like Hollywood, where people are paid vast amounts of money to perform in front of the camera, there is always going to be some sort of scandal. The lifestyle of the Hollywood celebrities lent itself to this sort of thing. The biggest studio in the 1920s and ‘30s was Metro Goldwyn Mayer, which claimed to ‘have more stars than are in heaven’. It’s logical to suppose then that, given the vast number of stars on contract with the studio, they would have the most headaches.

For example, Jean Harlow, MGM’s “Blonde Bombshell,” reportedly had an affair with a married director in the 1930s and there were reports of her becoming pregnant. George Reeves, famous for playing Superman in the 1950s, died in 1959 under mysterious circumstances — officially ruled a suicide, though rumours suggested foul play. Silent-film heartthrob, John Gilbert’s career suffered in the early sound era due to reported conflicts with studio executives, alcoholism, and personal scandals.

Famously, Hollywood gossip columnist Louella Parsons threatened to expose various stars’ private lives, including alleged affairs, sexuality, or misbehavior. All these examples, and many more, have one thing in common, Eddie ‘The Fixer’ Mannix.

Mannix’s start in show business was not exactly august. He was a small-time hoodlum and thug, terrorising patrons at the Palisades Amusement Park in Bergen County, New Jersey. The park was owned and run by Nicholas Schenck, who alongside his brother Joseph, would soon to become major players in the burgeoning film industry. When Mannix was caught, Schenck saw potential in the young man and, instead of punishing him, gave him a job in the park. Mannix flourished and soon made his way up the ranks to become the boss’ right-hand-man. It was Mannix’s job to ensure everything was done correctly and the operation was run smoothly. He was to iron out any wrinkles that may crop up and threaten Schenck’s operations.

Schenck teamed up with Marcus Leow (of Loew’s Theatres) who was especially important to Hollywood due to the sheer number of theatres that he owned. In 1924, Loew brought together three prominent producers – Metro Pictures, Goldwyn Pictures, and Louis B. Mayer Pictures – and formed Metro Goldwyn Mayer (MGM). Louis B. Mayer was put in charge of the new studio although he was never entirely trusted or liked by Loew or Schenck. Mannix was sent to California by Schenck as a studio executive ostensibly to spy on Mayer and report back to New York. He was there to look after his boss’ interests and this he did with thoroughness and relentless passion.

Mannix was a tough guy who liked to hang out with other tough guys. It is said he had links with organised crime and undoubtedly felt comfortable dealing with the police and the press, many of them were easily bent to his ways. He was the muscle who had a hell of a lot of money behind him, and he was determined to make a name for himself in the business. So, when Hal LeSueur came to MGM looking for cash, it was Mannix who fixed everything.

According to speculative accounts, Mannix used his connections to track down the film’s producers and distributors. He allegedly paid over $100,000 — a staggering sum at the time — to buy and destroy the negatives. Some versions of the story claim that Mannix also used threats and violence to ensure the film never resurfaced. Given his known personality, this seems at least believable. One oft mentioned, but unverified quote from Mannix was:

“We bought every print of Velvet Lips we could find and burned them.”

Adding fuel to the rumor is Crawford’s $50,000 payment to MGM when she left the studio in 1943. Officially, the payment was for “studio expenses,” but some biographers suggest it may have been reimbursement for Mannix’s efforts to suppress the scandal. This payment is a little misleading as Crawford did not make any direct payments to the Studio. Instead, according to Donald Spoto’s, Possessed: The Life of Joan Crawford (2010), she forfeited unpaid bonuses and residuals and agreed to forego certain future earnings tied to in-progress projects. When leaving studios, stars did often pay expenses to their former employers, but this was usually because of a buyout by the star who wanted to leave the studio they had been contracted to. This was not necessarily the case with Crawford as she was, at the time, considered box office poison and the termination of her contract was with mutual consent. It is important to note that Crawford herself denied any involvement in adult films, calling the rumours “vicious lies” in her memoirs.

There is certainly reason to doubt the claims and the existence of Velvet Lips. Yet, given the circumstantial evidence and knowledge we have of Hollywood, pornography and the hardships that young would-be stars go through early in their careers, there is also enough believability to the story to make it intriguing. Looking through a modern prism, we could understand why Joan Crawford would appear in such a film and we would hardly judge her for it. Given her bad-girl image throughout her career, it would hardly have been contrary to what people thought of her. The 1920s and ‘30s however, were a very different time, especially given the moral crusades of the press and the influences of the Church at the time. This was the era of prohibition and the Hays Code after all.

Biographers remain divided. Some, like David Bret (Joan Crawford: Hollywood Martyr), have leaned into the scandal, citing unnamed sources and anecdotal evidence. He wrote that Crawford was blackmailed by family or others threatening to release the film(s).

“There is an entry in Joan’s FBI file stating that as much as $100,000 may have been handed over to this unknown blackmailer at around this time — and that MGM had made a previous payoff, almost certainly to the same man, who some believed to have been Joan’s brother, Hal.”

He even goes as far as claiming her mother had knowledge of it and was even involved:

“…her loathed mother forced Crawford to work as a prostitute, appear in pornographic films, and sleep her way to the top.”

Others, like Donald Spoto, have dismissed the rumors as plausible, but certainly without merit.

What is clear however, is that Hollywood’s studio system was built on secrecy. Stars were commodities, and their personal lives were tightly controlled. Fixers like Mannix operated in the shadows, ensuring that the public saw only what the studios wanted them to see.

Eddie Mannix died in 1963, taking many of Hollywood’s secrets with him. His legacy is one of power, manipulation and moral ambiguity. He was both protector and enforcer, a man who shaped the industry from behind the scenes.

Joan Crawford’s legacy is more complex. She remains one of the most iconic actresses of the 20th century, celebrated for her performances and her resilience. Yet her life was also marked by controversy, including her turbulent relationships, her feud with Bette Davis, and the explosive memoir, Mommie Dearest, written by her adopted daughter Christina. Christina doesn’t cover her mother’s early career and there is no mention of Velvet Lips. Instead she focuses on her mother’s abusive behaviour, alcoholism, and image-obsession.

The Velvet Lips rumor is part of Crawford’s mythos — a story that may never be proven but continues to fascinate. It speaks to the power of Hollywood’s illusion and to the lengths the industry went to to protect its stars. There were incredible pressures on women during this time and many were forced into prostitution. What’s more, there was an industry around the production and distribution of pornography that was, by the simple fact that it was illegal, manufactured and organised by criminals, thugs and petty gangsters.

In the end, the story of Eddie Mannix and Joan Crawford is less about what happened and more about what people believe happened. It’s a tale woven from whispers, shaped by the culture of secrecy that defined Hollywood’s Golden Age. Whether Velvet Lips was real or imagined, the idea that a fixer like Mannix could erase such a scandal is entirely plausible.

The enduring fascination with this story reflects our collective curiosity about the hidden lives of celebrities, and the machinery that kept their secrets buried. It reminds us that behind every star is a shadow, and sometimes, the shadow tells the more compelling story. Even if it is a shadow of something that lacks substance.