The Brothers and Sisters of the Toda Family: Ozu’s Lesser Masterwork.

Recently in the third in our series of retrospectives on some of my favourite films from Japanese cinema, I wrote of my love for Yasujiro Ozu’s masterpiece Tokyo Story. It is a film which, despite being made by the ‘most Japanese of film-makers’ is universal in its themes. It focuses on issues which Ozu seemed to obsess about, the relationship between parents and children, of the changing attitudes to traditions and the disappointments of life.

He would return to these themes over and over again with a keen eye and a sharpness of execution which is difficult to ignore. Even his lesser films explore these themes in a way which is heartfelt and that other filmmakers would struggle to achieve.

The edition of Tokyo Story upon which my review was based was issued by the BFI (British Film Institute) and is let down by a complete lack of extras. There is so much about the director, his approach, the country and the era in which they were made that could have filled several discs but sadly there is nothing. This however, is somewhat compensated by the accompanying booklet and a copy of another of Ozu’s films, The Brothers and Sisters of the Toda Family.

Like Tokyo Story, Brothers and Sisters is about generational tensions. The father dies having accumulated a large number of loans and other debts, leaving the mother and youngest daughter, Setsuko homeless. They move into the home of the eldest son whose wife resents their presence. She doesn’t address her in-laws directly at first though instead complains to her husband about the noise of the piano and the cost of keeping the two guests. Like Tomi in Tokyo Story, the mother acts perfectly stoically and it is Setsuko who complains, although in the familial hierarchy of Japanese society she has very little influence. Each generation reacts to the situation differently based on what they have grown to expect. The mother and daughter then move into the home of the next eldest son but again things don’t work out. It is up to the youngest son who has been away working in China to come home and sort things out for them, exposing the selfishness of his family.

In additional to the generational issues, here Ozu also tackles class. When Setsuko tries to get a job so that she and her mother can have money, she is stopped by her elder brother because this would not be fitting for the daughter of a wealthy man. Again her siblings are more concerned with how it reflects on them than the plight of their own family. It is a very simple premise told simply, however it is handled with such efficiency and with characteristic style that it is elevated above what could have been a maudlin and depressing tale.

Ozu developed a very distinct style early in his career and rarely deviated from it. He would use long takes shot from low angles, viewing the action as if from a kneeling position on a tatami mat. He often created frames within frames and rarely used close-ups. Between scenes he would place shots of rooms or inanimate objects which seemed isolated yet added to the atmosphere. They have been labelled ‘Pillow Shots’ and act as moments of quiet reflection between the action allowing us to contemplate what has happened and what will happen.

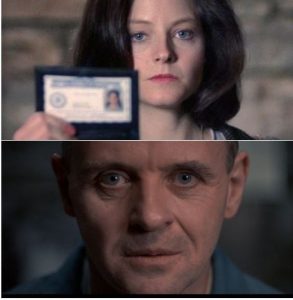

Another method which is very distinctive of Ozu is his approach to filming conversations. Normally filmmakers follow the 180-degree rule in which the two people speaking are placed on one side of an imaginary line and the camera on the other, recording each person from an angle. This gives the impression that the characters are looking at each other. Ozu mostly dispensed with this rule instead filming the speaking character face on, as if they are speaking directly to the camera. Instead of the camera being the other side of an imaginary line, it is between the speakers so the camera becomes the character. Initially this approach seems quite odd – we are certainly not used to it – but after a while it seems the most natural thing in the world. For another example of the effectiveness of this style of filming dialogue look no further than Jonathan Demme who used it frequently. The interviews between Clarice Starling and Hannibal Lecter are given extra menace because of a style of film-making developed by the gentlest of filmmakers. It is a style which owes everything to the quiet, unassuming and very Japanese Yasujiro Ozu.

Another method which is very distinctive of Ozu is his approach to filming conversations. Normally filmmakers follow the 180-degree rule in which the two people speaking are placed on one side of an imaginary line and the camera on the other, recording each person from an angle. This gives the impression that the characters are looking at each other. Ozu mostly dispensed with this rule instead filming the speaking character face on, as if they are speaking directly to the camera. Instead of the camera being the other side of an imaginary line, it is between the speakers so the camera becomes the character. Initially this approach seems quite odd – we are certainly not used to it – but after a while it seems the most natural thing in the world. For another example of the effectiveness of this style of filming dialogue look no further than Jonathan Demme who used it frequently. The interviews between Clarice Starling and Hannibal Lecter are given extra menace because of a style of film-making developed by the gentlest of filmmakers. It is a style which owes everything to the quiet, unassuming and very Japanese Yasujiro Ozu.

The Brothers and Sisters of the Toda family may not be the best of Ozu’s considerable oeuvre but it is an extremely affecting film. If anything it illustrates how great his masterpieces were as a film like this would have been revered in the filmography of most other directors.