Ghost in the Shell (1995).

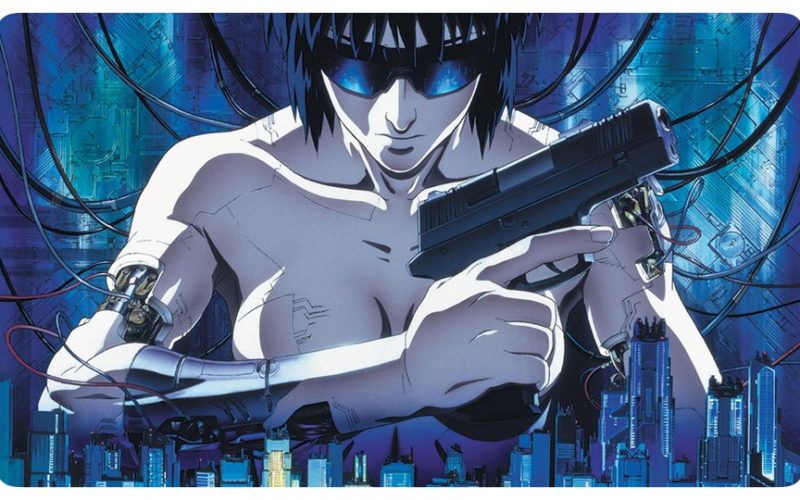

When Major Kusanagi of Section Nine, an elite police division, looks long enough at us through the screen, we realise that she doesn’t blink. It’s one of many very deliberate choices in Mamoru Oshii’s now legendary science fiction classic, Ghost in the Shell. He wants the Major to appear doll-like, not quite enough like us despite her feminine voice and her human appearance. Our first instinct, particularly when seeing her superhuman abilities in the film’s opening sequence, is to disregard her as little more than a cyborg, but the film spends the rest of its brisk 83 minute run-time destabilizing that line of thinking without actually giving any right or wrong answers.

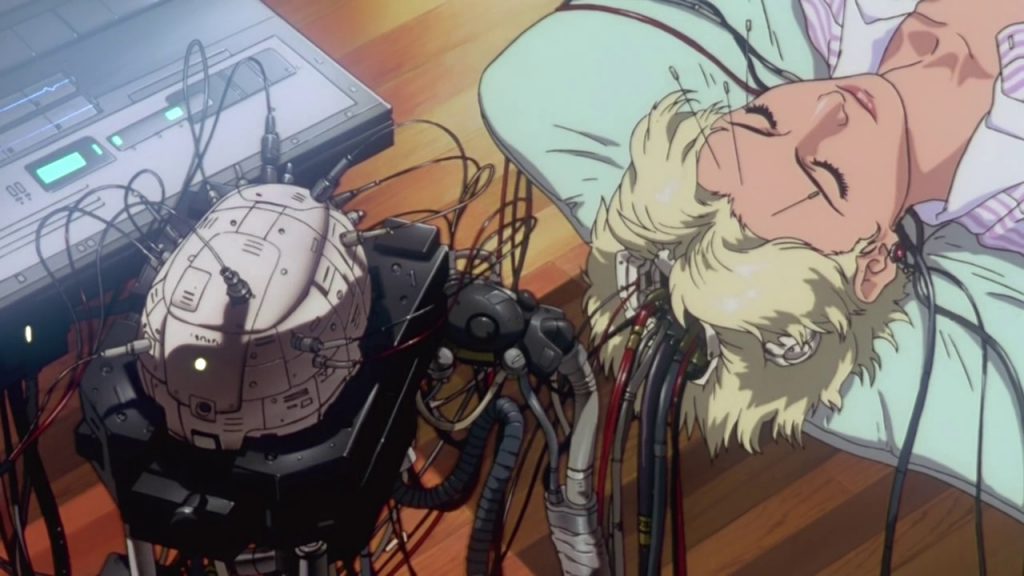

Identity and the value of life are the themes at the heart of Ghost in the Shell, with sexuality, privacy, and political interference observed to lesser but not under-served extents. It’s an ironically heartless film but not one bereft of a soul. It’s a cold, calculated, machine-like work of art that demands the mildest of emotional investment from its viewer and yet doesn’t suffer for it. Set in 2029 and based on Shirow Masamune’s manga of the same name, the human race has reached its technological peak. Most are, to at least some extent, cybernetically enhanced. Many are more cybernetic than human, possessing only the “ghost” that may or may not be the remains of their human consciousness.

The Major’s team is tasked with tracking down the Puppet Master, a cyber criminal that’s hacking into people’s cyberbrains to procure information and commit further crimes. This premise itself lends the film, and the entire franchise really, the classification of a post-cyberpunk story. Cyberpunk often preoccupies itself with the action and inaction of morally ambiguous figures fighting against some form of oppressive regime or a world marred by corruption and poverty.

The characters of Ghost in the Shell, contrarily, more or less fight the good fight. As members of the police force they do not exist to rebel, nor do they act out of self-preservation – quite the opposite in fact. They are not in opposition to the establishment but rather tasked with maintaining it, suggesting that civilization is not the cesspool that cyberpunk is so often preoccupied with. Ultimately, cyberpunk treats its futuristic world and its technological reliance as a deeply frightening and damaging prospect. Ghost in the Shell treats it as a necessary part of human evolution and experience. It deals with the effect of cybernetics and the mistreatment of technology without ever claiming that the technology itself is to blame.

Oshii meticulously molds his use of technology with sizzling, brutal bursts of action, giving every unique element of this futuristic world a use rather than using it for cosmetic purposes. Often, near-future science-fiction throws its shiny toys into the sandpit simply for the sake of it. Here, everything is given a setup and a payoff. The most obvious example is Kusanagi’s thermoptic camouflage, used in the film’s astonishing opening sequence and then twice again later on. Oshii uses such basic visual tricks to avoid exposition and introduce the various physical elements in a wordless, concise manner, and slow-motion is used as a tool rather than a gimmick.

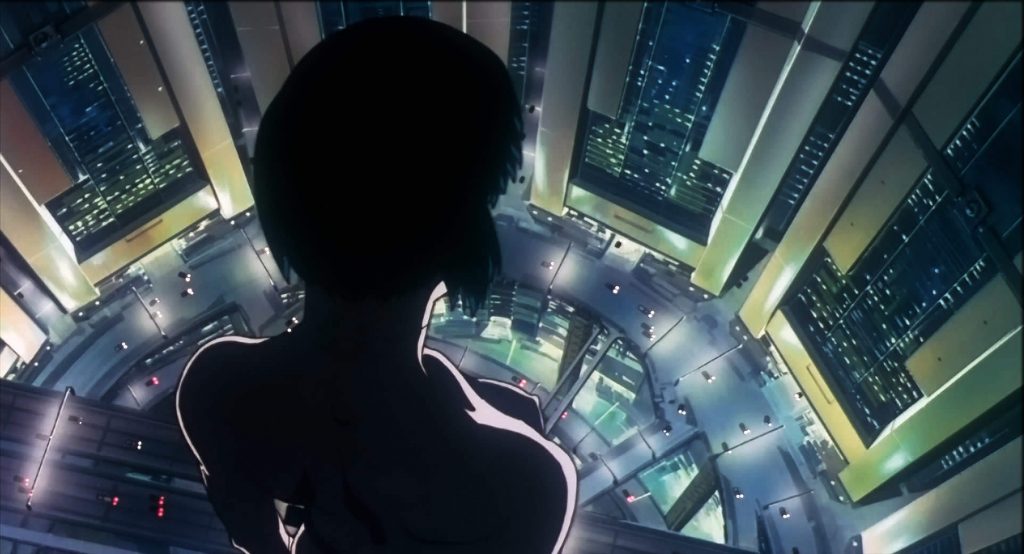

The film unfolds the same way a procedural might, with the officers of Section Nine following a lead that could help them catch the notorious Puppet Master. The pursuit of the garbage disposal truck is tense, manufactured almost solely through careful, minimalist editing. Oshii revels in holding single frames for longer than we’re accustomed to, such as during the final segment of the pursuit in which Kusanagi makes short work of one of the Puppet Master’s various pawns against the urban, decaying backdrop of the city. Curiously, before his capture, the cyber-hacked man pauses and lets out a half-smile at the more alluring, romantic city skyline on the other side of the water, lost in the moment as if forgetting that he’s being hotly pursued by the law.

This serves as further proof that the film does not loiter on the poor state of society and its infrastructure. Instead, the city is used as a kind of exterior visual metaphor for the complex moral state of humanity and the ever growing complexity of the online world. Once the Puppet Master is captured, the film dives headlong into themes of existence and the value and definition of sentient life. Where Kusanagi is riddled with uncertainty about her own identity despite her thirst to realize her destiny, the Puppet Master is secure in his own belief that he deserves the same rights as the humans he interacts with.

The reveal that he is but a program that’s grown from humble beginnings to something willing to debate the definition of memory and why his existence is no less valid than that of a humans directly links with Kusanagi’s search for inner validation and search for purpose outside of the rules that she is governed by. When she dives under the water, she’s looking for a chance to feel. Her words are powerful, even if her tone is unchanging and her eyes unblinking. How much humanity remains in her is never made entirely clear, and her behaviour frequently suggests that she consists more of cybernetic parts than human cells. And yet, there’s far more to her than nuts and bolts.

She’s unperturbed in any state of undress, a point made clear when, curiously, Batou exhibits more “human” qualities as we understand them – he notably turns his head away in discomfort when he spots Kusanagi getting undressed, and elsewhere makes a point to put a coat over her exposed body. Kusanagi’s behaviour not only acts as a distinguishing facet of her “otherness” but also challenges the patriarchal expectation of women in our society. Outside of her physical “lack of foresight”, there are various comments made toward her behaviour and temper, moments that stand out even more-so due to either her absence or her disregard for them.

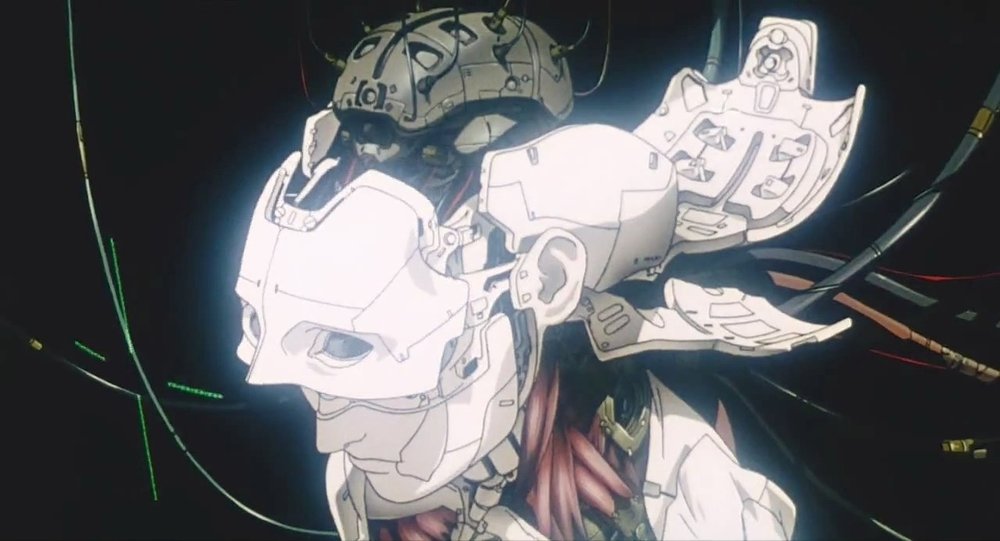

The film makes an inspired choice, and the only logical one in line with its themes, by switching its antagonists. In the third act, the Puppet Master is not the villain but instead resembles something of a MacGuffin, and later a catalyst for where Kusanagi’s entire journey has been leading to. The twist revealing the nature of the Puppet Master’s existence and our learning who the true antagonists are aligns with the heavily political undercurrent that was setup from the very beginning when Kusanagi takes out a government official. Her battle with the tank is rather cathartic thanks to Kenji Kawai’s mesmerizing music, and her subsequent conversation and ultimate decision is immensely satisfying. Batou observes the conversation that the two have, but only hears half of it. He’s a stand-in for us, utterly perplexed by the notions being juggled and bewildered by the apparent disregard both the Puppet Master and Kusanagi have for their own individual lives. This isn’t to suggest that the film dismisses its audience, but rather that it challenges us to dive in with Kusanagi rather than stand aimlessly beside Batou looking in from the outside.

Ghost in the Shell is that rare accomplishment. At such a short length, it is a loaded, heavily philosophical journey that invites multiple readings and interpretations, but remains immensely entertaining at the same time. The action is superb, the visuals are ageless, and the story is stirring. Both the Japanese language original and English language dub versions are solid, even if the English version makes the occasional change that misses the point of the original line. The film was the first to be released outside of Japan at the same time as its Japanese release, a decision intended to help the growth of Anime across the world. It failed at the box office but its fame grew after its home video release. It is one of the leanest and yet most thoughtful films of its kind, and few films of its quality can compare to its ambition and undying societal relevance.

Film ‘89 Verdict – 10/10

Ghost in the Shell is available on Blu-Ray in most regions.