Yasujiro Ozu’s Tokyo Story (1953) – A very human tale.

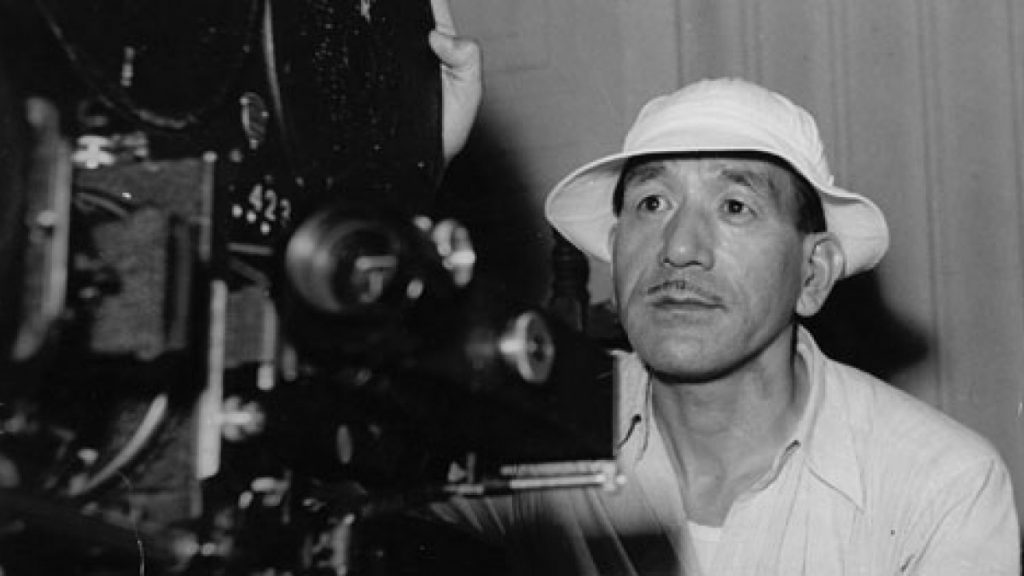

There have been few films which have managed to balance being stylistically distinctive, psychologically interesting, culturally enlightening and, to top it all, entertaining. It’s a list populated by some of the true greats of cinema; Citizen Kane, The Godfather, Taxi Driver, Sunrise. These films were made by directors who understood the nature and art of cinema; Welles, Scorsese, Coppola, Murnau. One of these giants is a Japanese director who died before the world discovered his films and so was never able to appreciate the influence and love he now commends, Yasujiro Ozu.

If you haven’t heard of him then that’s understandable. He was known as being ‘the most Japanese of directors’ and his films are glimpses into the culture, hierarchy and personality of Japan with little interest of the outside world. Yet for many filmmakers and critics he is revered and ranks with the greatest names in filmmaking. His films tell small personal stories that represent the time they were made and the transformation that Japan was going through before and after World War II. They eschew politics, focusing instead on the minutiae of Japanese life, addressing change through generational rather than state politics. The renowned film critic Roger Ebert once said “To love movies without loving Ozu is an impossibility.”

I had wanted to see his most famous film, Tokyo Story for many years before I was finally able to track it down. It is a film that doesn’t get mentioned by mainstream media very often but its importance is undeniable. A lot was written of it a few years ago when Sight & Sound magazine published their 10-yearly poll of the greatest films of all time. People focused on the fact that Hitchcock’s Vertigo had finally disposed of Citizen Kane off the top position, where it had sat for 40 years. Kane dropped to number two on the list but commentators seemed not to notice it shared this position with Tokyo Story. So high is the regard for this film that it was given the same esteem as Welles’s much trumpeted masterpiece and yet, to the world at large, it was as if it didn’t exist.

This is the travesty of a media that are more interested in headlines than facts. The fact that Citizen Kane was toppled was news, the fact that Vertigo, as film made by an English born director, Alfred Hitchcock, was especially big news in the British Media. But the importance of a Japanese film, directed by someone most commentators had never heard of, wasn’t worthy of notice. Yet, amongst filmmakers and critics it is a film which continues to influence and to inspire.

Released in 1953 Tokyo Story tells the simple story of an elderly couple, Shūkichi and Tomi Hirayama (Chishū Ryū and Chieko Higashiyama), who travel to the city to spend time with their children and grandchildren. When they arrive they discover their family doesn’t have time for them. Their daughter, Shige, is a hairdresser who always seems too busy and is the mother of a rebellious young boy and their son Kōichi is a pediatrician who always seems to be out on call. They are people with lives of their own and seem to think of their parents as an unnecessary intrusion rather than showing them the respect they deserve. They justify their actions by claiming that their parents don’t understand how busy their lives are and that they are only looking out for the old folks. In one scene the parents are sent off to a spa where they are surrounded by youngsters listening to modern music. Shūkichi and Tomi are completely out of their depths and ill at ease yet they continue the illusion themselves, worrying that the spa would cost too much money and they are very lucky to have children who would treat them to such a gift.

The only person who has time for them is Noriko, the widow of another son who had died in the war. Played by the wonderful Setsuko Hara, Noriko understands the disappointment of life and has learned to live with it. This gives her empathy and understanding for her in-law’s plight that the others seem to lack.

The only person who has time for them is Noriko, the widow of another son who had died in the war. Played by the wonderful Setsuko Hara, Noriko understands the disappointment of life and has learned to live with it. This gives her empathy and understanding for her in-law’s plight that the others seem to lack.

It’s a complex film about generational changes and expectations, of the disappointments in life and of the illusions we all live with. Occasionally these illusions are broken and truths are revealed. Tomi has had to put up with her husband’s drinking throughout their marriage, both Tomi and Shūkichi discover that their very successful children are not as successful as they initially thought and their children do not share the same values or principles as their parents. These truths are accepted and justified with further illusions and excuses.

Shukichi Hirayama: “I’m surprised how children change. Shige used to be much nicer before. A married daughter is like a stranger.”

Tomi Hirayama: “Koichi has changed too. He used to be such a nice boy.”

Shukichi Hirayama: “Children don’t live up to their parents’ expectations. Let’s just be happy that they’re better than most.”

Chishū Ryū and Chieko Higashiyama both perform with a detachment and control that almost seems like a blank canvass onto which we are able to project our own disgust and dislike for the way they are treated.

I have seen Tokyo Story four times now and each time I am moved by the callousness of the family members and how this apparent passiveness of the parents makes it all seem worse. Towards the end it is the youngest daughter, Kyoko, who must learn this hard and tragic truth, something she verbalises in a conversation with Noriko. “Isn’t life disappointing?”asks Kyoko, “Yes, it is” replies Noriko.

This is why Ozu’s films are often seen as ‘too Japanese’ because the characters react to their problems within the expectations and culture they live in and not with the histrionics we would expect from an American melodrama of the time. But this objection misses the point – to watch a foreign language film should not have to mean watching a Hollywood style film in another language. We watch films from around the world to discover and enjoy the cultures of the world. To expose ourselves to the influences of other people and other approaches.

This is one of the reasons Ozu’s films are so important, so moving and so wonderful. They present us with very real, very human problems in a way which is both foreign to us, but also because of their humanity, very intimate and recognisable. His visual style was so distinct that they are essential viewing for any cinephile but the themes he obsesses about in film after film make them essential for anyone of us who want insight into who we are. This is not a Japanese approach, it is a very human one.