The Last Temptation of Christ (1988).

Martin Scorsese has never been a stranger to controversy. In 1981 John Hinckley attempted to assassinate Ronald Reagan having been apparently inspired by an infatuation with Jodi Foster and Scorsese’s 1976 film Taxi Driver in which Robert De Niro’s Travis Bickle tries to kill a candidate running for Senator. Throughout his career he’s been attacked for not fully denouncing the vilest instincts of his characters, something that seemed to reach a crescendo in his 2013 film, The Wolf Of Wall Street. There has also been continued accusations that his films are misogynistic and that he doesn’t understand, or wants to represent, women in his movies. The biggest controversy of his career however, occurred in 1988 with the release of his religious masterwerk, The Last Temptation of Christ.

A keen reader may have noticed the lack of the word ‘biopic’ in that last sentence. Many have called it a biopic of Jesus Christ, however, before the film starts, we’re informed that it isn’t based on the gospels. Although many of the events of the film will be recognisable to anyone who knows even a little about the Bible, the interpretation and the meaning has shifted beyond what we previously understood.

Aiden Quinn was originally cast as Jesus and Sting was to be Pontius Pilate but because of the troubled production the film was cancelled at one point by Paramount Pictures and its parent company Gulf & Western, who decided that the original budget of $14 million was too steep.

Scorsese then made his New York comedy After Hours before returning to the material when Universal expressed an interest. The final film cost $7 million and was filmed in Morocco in only 58 days. This narrow production window undoubtedly contributed to the look of the film which, despite some flourishes with the camera, is stripped down and more minimalist than it might have been. Fittingly for its subject matter, filming wrapped on Christmas Day 1987.

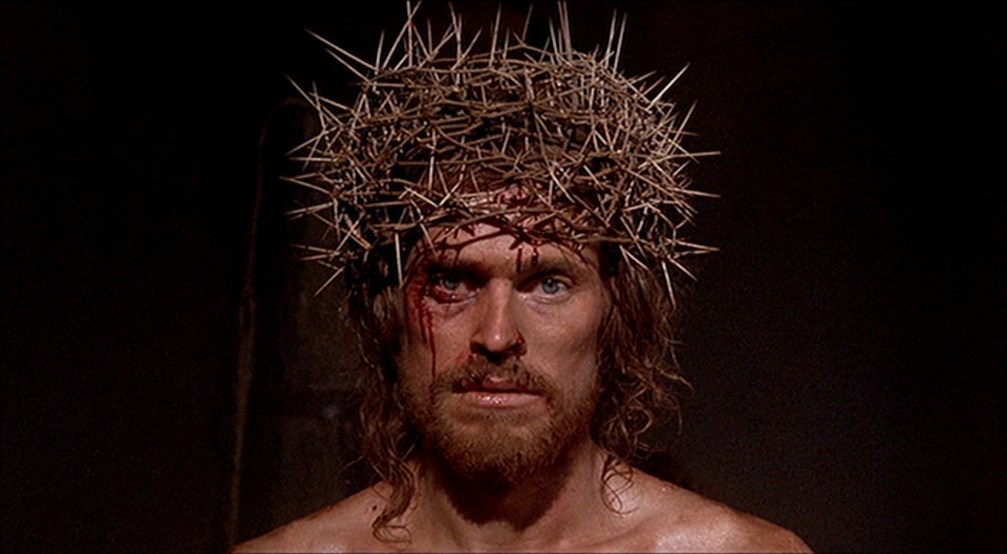

The casting is particularly interesting as the decision was made to allow actors to use their own accents and act in a naturalistic manner that was different to previous incarnations of the story. After Aiden Quinn and Sting dropped out, Willem Dafoe was cast as Jesus and the role of Pontius Pilate went to David Bowie, who, along with Harvey Keitel’s brilliant turn as Judas, contributed to a very blue collar film and even though Last Temptation isn’t supposed to be based on the gospels, it does prove to be the most authentic mise en scene since Pasolini’s The Gospel According to Matthew.

This last comparison highlights a significant issue that all filmmakers approaching the life of Christ have to confront. Pasolini – a gay, Marxist, atheist – was perhaps the last person one would expect to approach this subject, yet The Gospel According to Matthew adheres attentively to the source material whilst capturing the proletariat themes of the gospel that are often forgotten in this time when Christianity is often summed up by the excesses of the organised churches (think of the extravagant pageantry of the Catholic Church or the Prosperity teachings of many protestant preachers).

Likewise, Scorsese – a director who at one time thought of becoming a priest and has always been open about his Catholicism – seemed an unlikely choice to make perhaps the most controversial and, to many people, blasphemous biblical retelling.

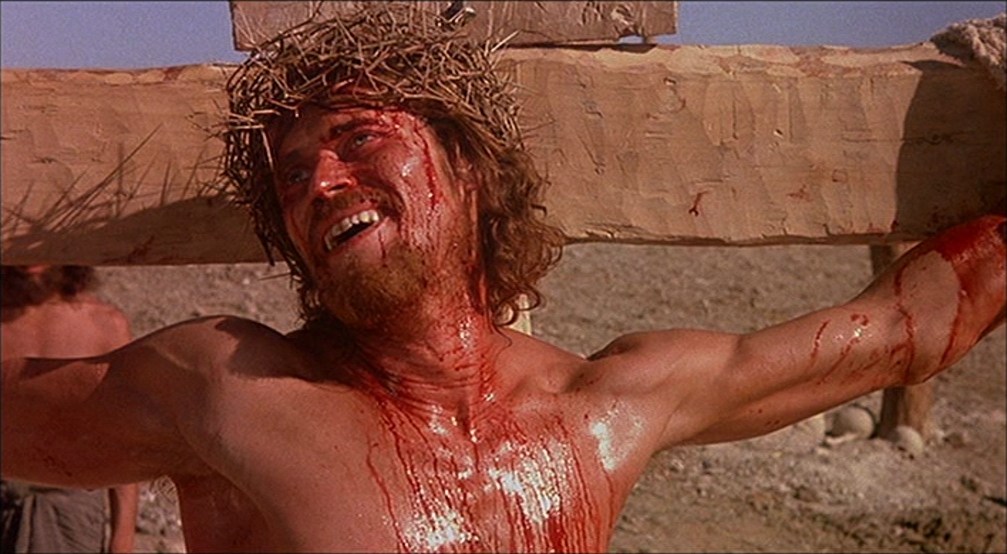

Both films use a stripped down minimalist approach which attempted to present the protagonists as real people, without the fawning, worshipful attitudes that marred other versions of the gospel. Even Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ, a film renowned for its realistic approach to the violence and suffering that Jesus was subjected to, couldn’t resist presenting Jesus with such reverence that he is almost stripped of personality. This is of course a difficulty that any filmmaker, especially one who is devout, will face. Rowan Williams, the ex-Archbishop of Canterbury (the head of the Church of England), has admitted that, based on the Bible, it is impossible to understand the true psychology of Christ. This is in part because we are not told of this aspect of Jesus in the Gospels. Instead we are told that he was both God and man at the same time.

How can a mere mortal conceive something like this? It’s too tempting not to try anything with it and instead present Jesus as orthodoxy dictates. This is not meant as a criticism, especially as most people who approach this subject have preexistent notions of the man based on their own faith and, dare I say it, ideology. Pasolini’s Jesus, for example, may have been the closest to the gospels (much of the dialogue was taken ad verbatim from the Bible) but he was also a perfect vessel to challenge the status quo of post war and post fascist Italy. In the words of Roger Ebert, ‘[Pasolini’s Jesus’] words are clearly a radical rebuke of his society, its materialism, and the way it values the rich and powerful over the weak and poor. No one who listens to this Jesus could confuse him for a defender of prosperity, although many of his followers have believed he rewards them with affluence.’

Dafoe’s Christ, as written originally by Kazantzakis and interpreted by Schrader and Scorsese, is in no way serene. He is a man conflicted and almost in constant pain – not physical but spiritual and existential. As I alluded to earlier, this is not a biography of Jesus and neither is it a devotion. In fact, although the main character is Jesus, this character is not just the man who inspired the biggest religion in the world and it is something that, in my experience, people had the most difficulty with when watching Last Temptation.

The truth is that here Jesus represents not just the God but also the believer. He is a manifestation of the Christian who has faith but struggles with questions, both internal (for example, how do you reconcile the God of love with the death of loved ones and the difficulty of your own life) and external (standing up for your beliefs in the face of an atheistic and sometimes hostile world). The reason we have difficulty imagining the psychology of a messiah is because we can’t imagine being one ourselves, yet the Christian faith calls for us to try and be perfect, whilst recognising the impossibility of achieving it. As the father exclaims in Mark, Chapter 9, ‘I believe, help my unbelief.’

Scorsese was obviously drawn to this conflict. He has said in numerous interviews, the Jesus in his film is intended to make him more relatable and, in extension, more believable. This is also one of the reasons he decided to forgo the pretense of having authentic accents. He wanted modern audiences to hear the differences and know, almost instinctively, that a particular person was from a different part of the country or the world. It’s this authenticy, completely stripped of pageantry, that Scorsese found so interesting in the Pasolini film.

Major events which are lionised in the Christian Church – for example, the Sermon on the Mount – are presented in a much more realistic and smaller scale. There are no massive crowds who, despite being half a mile away, are still able to hear every world that Jesus speaks. This is something that Monty Python immortalised in Life of Brian (‘Blessed are the cheesemakers?!’) but again, a more devout filmmaker may ignore.

Another scene of note is the resurrection of Lazarus. There is a palpable sense of anticipation as Jesus calls the dead man to rise and I realised that, because of the very different approach the film takes, I didn’t know what to expect when first watching it. Everything that precedes it and yes, all the controversy that surrounded the movie, wrong-foots us so that our expectations are subverted. When the stone is rolled back everyone recoils because of the stench of decay that escapes the tomb. Then, when Lazarus reaches up from the darkness of the grave, I physically jumped. His hands are not clean, they are dirty, worn, the hands of the dead. When he’s later asked which is better, life or death, Lazarus – and by extension the writers – let the ambiguity hang in the air, “They are just about the same”, he replies.

The performances throughout are excellent, especially Harvey Keitel’s Judas which is a role that is much more prominent than in previous versions of the story. Here he is a zealot sent to kill Jesus but ends up the most devout of followers. It is because of the strength of his relationship that he is the one chosen to betray Jesus. There are no airs and graces with this portrayal. Judas is presented as a hard man, a working-class hoodlum who has discovered a faith in someone he probably thought was beyond him.

Dafoe has undoubtedly the most difficult role in the film but he attacks it courageously and with plenty of emotion. We soon accept this variation of Christ because of his performance. It is naive and hopeful but pained throughout and his is a pain we can believe. He is a perfect conduit into this difficult subject matter.

Barbara Hershey was the person who first introduced Scorsese to the Kazantzakis book while they were filming Boxcar Bertha in 1972. Here she plays Mary Magdalene, a role that she had to audition for three times as Scorsese wanted to ensure that it wasn’t his personal bias that was casting her and that she really was right for the role. She’s outstanding in the part and very believable as a prostitute. This is not a ‘clean’ role as many Hollywood representations of prostitutes are (think Julia Roberts in Pretty Woman). There’s a sad desperation to her and Scorsese doesn’t flinch from showing her have sex with a number of men who are queueing up to be with her.

In fitting with the rest of the film, David Bowie’s brief scene as Pilate has none of the refinery of previous Biblical epics. His cloak is worn and dusty and he possesses a weariness of a bureaucrat rather than the pageantry of a ruler. When telling Jesus that he is going to be crucified at Golgotha, he sighs heavily and says: There will be 3000 skulls up there by now, I wish you people would go up there and just count them.’

Finally, Harry Dean Stanton has a brief appearance as Saul/Paul, the zealot who once persecuted Jesus but later was converted on the famous road to Damascus. His final sermon, in which he is confronted by the released Jesus, is very much akin to the modern preacher we see on TV. He also sums up the importance of Jesus’s sacrifice and what it meant for early Christians.

The pivotal moment in the film of course, is the last temptation itself. This is the moment which causes more controversy, especially to those who haven’t seen the film and therefore don’t understand the meaning or context of it. Jesus is on the cross and he is told by a child who claims she is his angel, that his mission is complete, that the sacrifice was enough and now he can go live an ordinary life. He was never the messiah and he can now just be the man he always wanted to be. He is able to get down off the cross and live an ordinary life, get married and have children. In Gethsemane he prayed to God to take the cup from him so that he doesn’t have to drink its bitter flavour, now he is told that this can be so.

The importance of this last sacrifice is that Jesus must understand that it was not God who told him to get down off the cross; it was the devil. He has been duped and his life since has been a lie. This is the true moment of sacrifice because Jesus no longer has to give up something that he never had – a wife and children – but something he has experienced, has loved, has enjoyed. This is a much greater sacrifice than anything that came before it and those who have not seen the film but decided it was blasphemous anyway, would never understand. Fittingly, it is Judas once more who tells him the truth, that the child he sees is not an angel but the devil himself.

The music by Peter Gabriel manages to be both exhilarating and mournful at the same time. The cinematography is wonderful, especially in the later scenes when the film takes on a more surrealist atmosphere and the editing by Thelma Schoonmaker is to the quality you would expect.

Martin Scorsese’s direction is, as is often the case, the real star here. He has never been a director to hide the process of film-making. His camera, whilst never invasive, is often the star of his movies – think of the wonderful entrance to the Copacabana nightclub in Goodfellas, or the finale of Taxi Driver as the camera surveys the carnage that Travis Bickle has left in his wake – and this is also the case here. There are some wonderful little flourishes throughout but the best is saved for the final moment. As Jesus realises that everything that was meant to happen has now happened and he looks serenely at everything that is taking place at that particular moment, he shouts out ‘It’s accomplished’ and, instead of fading to black, the film seems to unspool and the screen fills with the bright light of the projector. Scorsese’s two obsessions, film and religion, become one.

It was undoubtedly a difficult film to sell. It wouldn’t really draw in anyone who wasn’t a believer in the first place and, for those who are, the subject matter offers some great difficulties and requires an open mind. At the time of its release, open minds seemed to be in short supply as it proved very contentious indeed and, although I have alluded to this throughout, I don’t wish to dwell on it. It is difficult to judge the film because its subject matter is so personal, but, if you are willing to put all that aside, you will find a film that’s thought provoking, moving and ultimately, inspiring.

Last Temptation was the first in Scorsese’s religious trilogy and, whilst it may not be the best, is certainly a brilliant new take on a subject over two thousand years old.

Film ‘89 Verdict – 8/10