A Nightmare On Elm Street (1984).

One, two, Freddy’s coming for you.

When people list the greatest and most influential horror films of all time there are a number of films which always seem guaranteed to show up time and time again – The Cabinet of Dr Caligari, Nosferatu, The Bride of Frankenstein, Psycho, Night of the Living Dead, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and The Exorcist are all bound to make the list. They are the films which changed perceptions, pushed limits and made tons of money for the film industry. But there is one film which arguably changed not only the route that horror was taking at the time but also helped change modern cinema, built a film studio and created a character that has entered movie folklore. That film is A Nightmare on Elm Street.

Directed by Wes Craven, A Nightmare on Elm Street does something that great horror does better than just about any other genre. It takes a simple concept, something which is mundane, acceptable and mostly unassuming, and twists it until it drips blood. IT, the recent horror juggernaut directed by Andy Muschietti from the book by Stephen King did this with clowns, in The Exorcist it was faith, in Dawn of the Dead it was shopping and in A Nightmare on Elm Street it was sleep.

Sleep has been the subject of horror and fantasy since the dawn of cinema. An example is Robert Wiene’s Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1919) an obvious influence on Craven, in which the threat came from a somnambulist (the great Conrad Veidt) under the control of an evil hypnotist played by Werner Kraus (or did it? It may have been all a dream). The Wizard of Oz employed a similar approach with the whole adventure being revealed to be a dream in the last moments.

A Nightmare On Elm Street also questions the link between reality and the unreality of dreams, but unlike the two examples above, we soon discover that it is ‘all just a dream’ and, at the same time, it is so very violently real.

It tells the story of a small group of friends who, we discover, seem to be all sharing the same dream. In this dream they are being chased, taunted almost, by a grotesque figure with knives for fingers. Each one recounts the terrible sound these knives made when scraped across steel pipes, and how they are now afraid of falling asleep because the dreams were so disturbing.

Of course, it turns out that the creature that stalks them in their nightmares is not just a figment of their imaginations. He was a very real child killer named Fred Krueger, a man who was released by the police because of a technicality and was then hunted down and burned alive by a mob of vigilante parents. Now he’s back on a mission to punish the children of those who killed him and to continue indulging his perverse proclivities.

The start of the film is similar to Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho. We are first introduced to Tina, a young woman who we initially assume will be the main character. It is in Tina’s dreams that we first see Freddy and it is her fear that brings the group together. But, just like Marion Crane in Psycho, Tina is quickly and imaginatively dispatched and from here on we follow her best friend Nancy. The truth of what is happening dawns on Nancy gradually and there are no ‘eureka’ moments, something which gives the film a realism despite the fantastical premise.

Nancy’s mother Marge, convinced that there is nothing wrong with her daughter that a decent night’s sleep wouldn’t solve, takes Nancy to a sleep clinic, in a scene reminiscent of The Exorcist. After being awakened from another encounter with Freddy, Nancy manages the break the boundaries between dream and reality by bringing her antagonist’s hat from the dream state into our reality. It is at this point that the line between fantasy and reality, between nightmare and wakefulness and between imagination and the mundane is crossed. This is the power of film and it is something that Wes Craven beautifully exploits.

In the documentary Never Sleep Again (which is on the Blu-ray boxset of all seven Elm Street movies) Craven claims that, due to his parent’s strict Baptist beliefs, he wasn’t allowed to watch films as a child and it wasn’t until he was a teenager that he began to watch the classics, lapping them up with excitement. This avalanche of movies obviously had a great impact on him and he seemed to have imbibed these influences which, coupled with what is obviously a very natural talent, is very evident in this his seventh film as director.

His ability to identify common emotional and intellectual threads in life and to turn them into the fantastic and the horrible is something that must have been with him long before he turned to filmmaking. Indeed, he earned a degree in English & Psychology and a Master’s in Philosophy. His first job was in teaching but he soon bought a 16mm camera and started making short films. His first job in filmmaking was as a sound editor and his first directing roles were for porn films. Apparently, he even worked on the porn classic Deep Throat, although it’s not clear what that role was.

His proper directorial debut came with The Last House on the Left which Craven wrote, edited and directed. It was produced by his friend and director of Friday The 13th, Sean S. Cunningham and was inspired by, of all things, Ingmar Berman’s Swedish classic The Virgin Spring. The Last House On The Left soon became a cult classic, helped in a roundabout way by the British Board of Film Classification who refused to release it in the UK. In the 1980s it became a key film in the Video Nasty Scare.

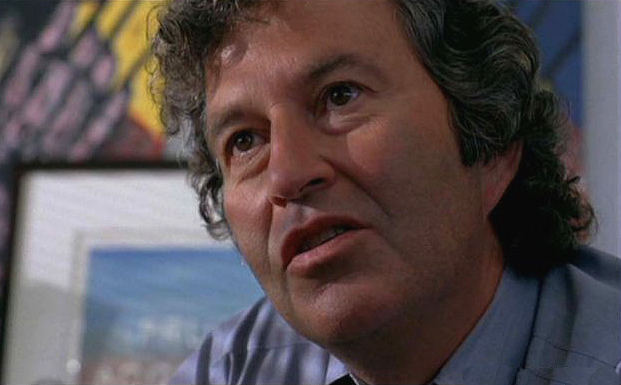

In the early ’80s Craven met with New Line producer Robert Shaye and they set out to make A Nightmare On Elm Street. Up to this point Newline was a small production and distribution company which specialised in horror because the genre tended to be cheaper to make and more likely to generate a small profit. In 1983 they also produced the John Waters film Polyester, which introduced the novelty of Odorama, a technique of using scratch & sniff cards allowing the audience to smell as well as watch the feature.

If Craven was the artistic force behind Nightmare, Shaye was almost everything else. He fought long and hard to secure funding for the film, constantly meeting and negotiating with financers and the stress on him was immense. Even before the filmmaking had begun all the initial financers backed out and, according to Shaye, half the funding came from a Yugoslavian who only wanted his girlfriend to appear in the movies. At one point Craven noticed that Shaye’s finger nails had been bitten so far to the quick that they were almost bleeding.

The finances were always precarious and Shaye had to rescue the film a week before its release after the processing company refused to release the prints as they hadn’t been paid. However, when it was released it caught the public’s imagination and its $1.8million budget soon became a $25 Million hit. Its influence became so entrenched that even Ronald Reagan once used it as a way of describing his political opponents.

The success of A Nightmare On Elm Street took New Line Cinema to a new level of success and helped turn the company into one of the most successful producers of horror in the ’80s and ’90s producing a number of sequels to Elm Street as well as the Final Destination and Critters series. In the ’90’s they also produced the David Fincher classic Se7en and eventually accrued enough clout to make The Lord of The Rings movies.

A Nightmare On Elm Street also helped establish the idea that a series of films could be made, not around a hero (such as James Bond) but around the villain and, alongside the equally successful Friday The 13th series, a new trend in cinema was established. Seven sequels of varying quality were released and in 2003, Krueger and Jason Voorhees were brought together for the successful Freddy Vs Jason (which grossed $114 million on a $30 Million budget).

But, apart from its obvious imaginative qualities, what is it that makes A Nightmare On Elm Street so successful and enduring?

Firstly it employs a very common trope of horror cinema, that of the teenagers in danger from an unrelenting force. This had already been used in such classics as The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), Halloween (1978) and Friday The 13th (1980) and was a way for the filmmakers to attract the youth audiences who had a taste for the horrific and the supernatural. Secondly, it exposes the fragility of the middle class during the Reagan era. Nancy’s parents are divorced, her mother is an alcoholic. Glen’s parents have little sense of the turmoil their children are going through after the death of one of their friends and schoolmates and the whole idea of middle class devotion to law and order is laid to waste when we discover it was the same parents who claim to be bastions of civility and society who formed the vigilante group that ultimately killed Krueger. The parents are in denial of their involvement and it is only Marge who will reluctantly admit to their involvement.

What A Nightmare On Elm Street did was breathe new life into this concept. Although the approaches made by Tobe Hooper with The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and John Carpenter’s Halloween were fresh, by the time Sean S. Cunnigham (who directed one of the action scenes in A Nightmare On Elm Street to help out as the film was over schedule) made Friday The 13th, the ideas were beginning to run out, and in 1984 the fourth of this series (the inaccurately titled The Final Chapter) was released. A Nightmare On Elm Street took this established idea and approached it from another angle – the antihero here was not someone who was endlessly coming back from the dead as, from the start of the film, he was already dead. And Freddy didn’t stalk the teens in some remote woods or even in their neighbourhoods, he stalked them in the one place we must all go, whoever we are, and where we are our most vulnerable – our sleep.

Horror has longed played with our subconscious and our imagination, it attacks us in places where we don’t like to think about, capitalising on our fears and bringing them to life. The most perfect example is of course the dark. When we see shadows, we don’t need to be shown a monster as our imagination will fill in the gaps for us. Just think of the swimming pool scene in Jacques Tourneur and Val Lewton’s Cat People. We don’t see the beast that is hunting Alice, the power of this scene is in the shadows, not in the cat itself.

A Nightmare On Elm Street plays with this early on. We do not see all of Freddy, he is hidden in the dark and with obscure angles. We don’t need to see him. All we need to see is his hands and the now iconic blades that he uses to slay his victims to know that he is a threat. When we do see him it’s because he wants us to see him and that’s when Craven’s imagination comes to the fore. As Freddy exists in the dream scape he is not bound by any laws of physics or biology. He can cut a finger off just to terrify his prey or stretch his arms to extreme lengths. When he comes into the real world it’s because the story demands it and, I think this is something which is often forgotten, he crosses over because Nancy wants to bring him over, to take away some of his power and to take control of the situation.

Just like Laurie in Halloween, Nancy is a strong young woman. This is something that horror excels at. It is often the female lead who is the focus of the film and they are also, more often than not, the one who defeats the monster. This is not only Laurie or Nancy, think about Ripley in Alien, Maddie in Hush or Sidney in Scream. They are women who must overcome the most terrifying of circumstances and prevail.

There are som fin acting performances in A Nightmare On Elm Street, especially Heather Langenkamp as Nancy and Ronee Blakley as the strung-out, drunk of a mother. The great John Saxon, who plays Nancy’s policeman father Don, is as stoic as ever and we also get Johnny Depp in his first screen role as Nancy’s very clean-cut boyfriend Glen. The star of the film, however, is undoubtedly Robert Englund who plays Freddy Krueger.

Today Freddy is an iconic figure. Even children born ten years after the film’s release can recognise this man who kills in your sleep and he was recently spotted in the trailer of the latest Steven Spielberg film Ready Player One. As played by Englund, Freddy is suitably scary. He is a hateful, malevolent creature who takes a great deal of pleasure terrorising the youngsters. Craven spoke of wanting to put a mask on him to add to the mystery, very much like Voorhees and Leatherface in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, but also wanted to do something that hadn’t been seen before. The final result comes from the script itself. Freddy had died in a fire so what better than to give him the look of a man whose face has been severely burned. His skin has been cauterised until we see only the remnants of muscle tissue and tendons. He walks with an unruly and ungainly manner; his voice is low as if his voice box has been charred yet his eyes are alive with evil intent. His dirty jumper is red and green chosen because these two colours are, apparently, most likely to clash on the human retina. But his most famous characteristics are the knives on his gloved hand. Just as Bela Lugosi held his long fingers out in front of him as he hypnotised his victim in Todd Browning’s Dracula, Freddy’s knives are an extension of his body which he uses to devastating effect. Each boogie man needs something that is unique, a hook if you will, that is distinct and terrifying and Freddy’s knives are some of the most famous weapons in the history of horror cinema.

The film also boasts an excellent score by Charles Bernstein which manages to capture both the thrills and the fears of this particular nightmare. With its simple refrain accompanied by a cool ’80s drum, the soundtrack fits the film perfectly.

If there is an issue with the film then it is the end. Ever since Carrie’s hand reached through the ground to grab Sue in Brian De Palma’s 1976 film of the same name, there has been a need to end horror films in a horrific way which will allow for the inevitable sequel. It is an ending that Craven resisted but Shaye pushed for. At first, it all seems as if the nightmare is over and that was all it was – a nasty nightmare which is behind them (it was all a dream) but as Nancy gets into Glen’s car and the sun roof comes down we see that it is the exact colors of Krueger’s jumper. There was talk of having Krueger driving the car but Craven didn’t want his monster to end up in the real world as this undermined the who premise. The final scene, which I won’t go into further detail, is an effective compromise but still unnecessary.

So, is A Nightmare On Elm Street still relevant? I would certainly say so. Not only is it very entertaining and has moments of genuine creepiness, but it also has a very original approach which puts it up there amongst the greatest horrors of all time. Horror has always had to compete with bigger budget, more prodigious and acceptable films and, whilst too many have been willing to ride the coat-tails of the greats without offering anything new or exciting, the best of horror reveals something about us and about the times we live in that other genres may not be able to address directly and A Nightmare On Elm Street is one of these movies.

Film ‘89 Verdict – 8/10