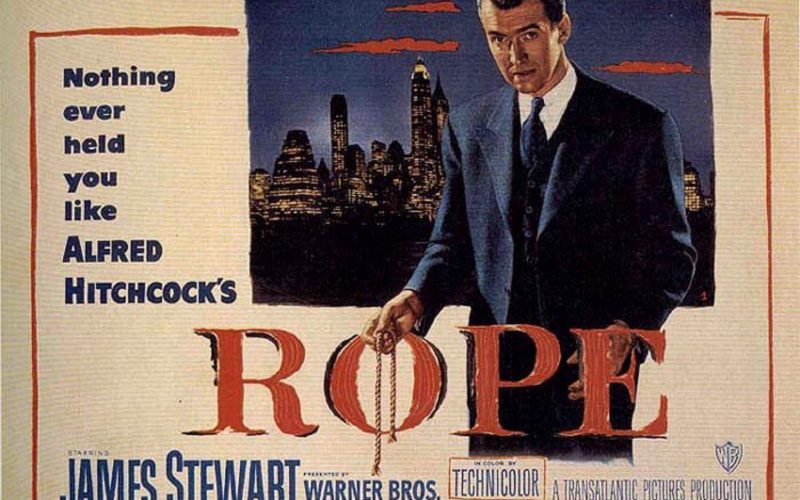

Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope (1948).

“The power to kill can be just as satisfying as the power to create.”

In 1948 Alfred Hitchcock took his first directorial step into the wonderful world of Technicolor with Rope. Aside from being the director’s first colour film, Rope would also take a unique place amongst Hitchcock’s filmography as being something of a bold experiment in long take filmmaking. Played out in virtual real time and employing a number of, at the time, clever technical slights of hand to mask the cuts (as well as conventional cuts) of which there are only 9, the film is very much a stage play acted out on the big screen with the illusion of being one long, uninterrupted take.

Rope is very loosely based on a real life murder committed by two University of Chicago students and a subsequent stage play by Patrick Hamilton. The film version sees Brandon Shaw played by John Dall, a self confessed “creature of whim” who considers himself “above the traditional moral concepts” act out a plan to commit the brazen murder of a fellow student with the assistance of his co-habiting friend, Phillip Morgan played by Farley Granger. Brandon and Phillip play it very much as a couple which was the cause of some controversy at the time of the film’s release. Such an overt representation of a gay relationship wouldn’t have been acceptable to audiences in 1948. Watching the film now, the homosexual undertones are very clear and credit to Hitchcock for showing such brazenness in the face of the general societal intolerances of the 1940’s.

Rope opens with the only exterior shot in the entire film and the camera then moves towards and into the apartment where the rest of the story unfolds. Immediately and with no build up or introduction we witness the murder by strangulation of Brandon and Phillip’s supposed friend and former fellow student, David with the murder weapon being the titular length of Rope. Without any context as to who is who at this point the viewer may feel a degree of detachment to the crime and this is likely wholly intentional on Hitchcock’s part. Rewatching it armed with the knowledge that the victim was lured to his death by two friends in order to satisfy a torrid fantasy that such a crime could be committed without the perpetrators being caught adds an entirely new and disturbing dimension to the film. It’s a murder completely devoid of motive, a murder they commit just to experience what it’s like to kill.

No sooner have Brandon and Phillip hidden the body in a large wooden chest, they then go about preparing for a dinner party for guests who will include David’s fiancée and father who will be enjoying their host’s food, drink and generous hospitality, completely oblivious to the fact that they are mere feet away from the dead body of a loved one. The sheer morbidity of this and the glee that Brandon displays makes the murder all the more reprehensible and again, this is something that becomes more apparent upon repeated viewings giving Rope a unique rewatchability that some of Hitchcock’s earlier, and dare I say less complex films may have lacked.

One of our party guests is Brandon’s former teacher, Rupert Cadell played by the legendary James Stewart. Rupert is a very astute man and seems to detect that something is awry fairly early into the party. Before his suspicions are fully aroused there’s a cute scene where our guests engage Rupert in a teasing discussion about their admiration of actors James Mason, Errol Flynn and Cary Grant replete with a wonderfully tongue in cheek reaction from Stewart, something that audiences at the time would have undoubtedly lapped up.

One of the most striking things about Rope is the clever depiction of the passage of time. The movie takes place in the one apartment with a wide rear window providing our only view of the cityscape outside. Beyond this window Hitchcock uses what is initially a rather unconvincing background diorama. When we first see it it appears to be mid afternoon but from here we witness the subtle transition from day through dusk to night as the background changes complete with lights in the windows of distant buildings. It’s a simple but effective device that is crucial to maintaining the illusion of the events taking place in real time.

An area of criticism that I couldn’t ignore and that pulled me out of the film somewhat was Phillip’s less than subtle reaction at seeing the murder weapon used to tie a pile of books. This crucial moment all but confirms Rupert’s suspicions but is uncomfortably overplayed by Granger. His reaction feels anything but organic and even though it’s made clear that he’s been coerced by the confident and domineering Brandon and is now deeply fearful of the reality of his predicament, the scene feels like a forced narrative convenience that’s beneath the director when considering his very best works. It could also be argued that the very confinements which define Rope also work against it. Visually we are given little to keep the eye occupied in comparison with some of the director’s more elaborate films. Some of the dialogue exchanges are superfluous and somewhat divergent from the progression of the plot but admittedly these aren’t factors that greatly hamper ones enjoyment of Rope.

Many of Rope’s strengths lie in the character of Brandon and the gross psychology behind what drives him to commit the murder. Brandon clearly has a God complex wrought out in his belief that “moral concepts of good and evil, right and wrong don’t hold for the intellectually superior”. His bastardisation of Rupert’s teachings makes the ending all the more powerful. I’ve often felt that certain films in the Master of Suspense’s oeuvre fall down somewhat at their conclusion. Saboteur’s latter half is full of messy convenience, Shadow of a Doubt’s ending feels rushed in spite of the languid pace of the film up to this point, even the wonderful North By Northwest ends with an abrupt sex gag. Rope however has a fittingly taught yet ultimately sobering finale as Stewart so ably conveys the abject horror at what his young wards have done in the name of their assumed intellectual superiority. There’s no violent death or cleverly staged comeuppance for either of our antagonists merely the brave actions of Rupert alerting the authorities to the plot he’s uncovered at the risk of providing the pair with another victim. It’s a beautifully sobering ending that leaves its mark and shows a wonderful degree of restraint from the often showy director.

Ultimately there’s a great deal about Hitchcock’s Rope that makes it one of the films that demands to be seen over some of his more conventional works. The bold, controversy baiting sexual undertones and strong moral message coupled with the unique one-take approach and stage play trappings makes Rope one of the standout films of Hitchcock’s 1940’s output and of his career as a whole and that’s as strong a recommendation as any.

Film ‘89 Verdict – 8/10