An Examination of Horror and Suspense In Classic Cinema.

There are many ways to do horror but essentially it comes down to two things: the set-up and the payoff. The set-up is the setting of the mood, the creation of atmosphere, of anticipation and expectation. This is not always the easiest of things to create and it’s even more difficult to maintain.

Think of the opening five minutes of Aliens Vs. Predator: Requiem, it has a lot of potential, plenty of history and expectation because of the previous films; it involves iconic monsters from two of the greatest science fiction films of all time dropped straight into our world and, most of all, it had a huge amount of good-will behind it from fans. Yet by the end of this five minutes it is obvious that the tension will not be maintained, the story and action will be rushed and the payoff will be a letdown.

Think of the opening five minutes of Aliens Vs. Predator: Requiem, it has a lot of potential, plenty of history and expectation because of the previous films; it involves iconic monsters from two of the greatest science fiction films of all time dropped straight into our world and, most of all, it had a huge amount of good-will behind it from fans. Yet by the end of this five minutes it is obvious that the tension will not be maintained, the story and action will be rushed and the payoff will be a letdown.

Now compare that with Psycho (an unfair comparison, I know). By the time Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) gets into the shower we know that something is going to happen. Hitchcock takes his time, cranking up the tension, giving the audience a sense of unease. We don’t know what is going to happen but we know something will, this is Hitchcock after all. We have witnessed Crane steal a significant amount of money from a client, the moment she decides to leave town only for her boss, who believes her to be ill, to see her at the crossing; the pursuit by the policeman on the motor bike who is made more threatening and unknowable because of his sun glasses. Hitchcock has taken his time to put us in a state of unease, to crank up the tension and to telegraph the fact that something is going to happen whilst keeping us completely in the dark as to what IS going to happen.

Then the payoff; as the shower curtain is pulled aside we are on edge yet did anyone see that coming? The audience expect one thing, Hitchcock gives them something even more shocking. The twist works because of the audience’s expectations, because our stomachs have been slowly twisted and tightened.

In Jacques Tourneur’s Cat People, Alice Moore (Jane Randolph) is walking alone on a quiet street, she is being followed by Irena Reed (Simone Simon) the wife of Oliver Reed (Kent Smith) who Alice has fallen in love with. What is Irena going to do? What has the ancient curse of the Cat People she is obsessed with got to do with it? The street is empty, the shadows are dark, the sound echoes. Like Hitchcock, Tourneur has twisted our stomachs, only this time he has something different up his sleeves to Hitchcock. There is a loud noise making us jump in our seats, only it is not a cat or a deranged and jealous woman leaping from the shadows, it’s the squealing breaks of a bus which stops right in front of her. This is a technique that has been utilised countless times in the decades since although more often than not the noise comes from the composer who cranks the volume right up to eleven in order to get the requisite jump.

But Tourneur is not finished. There is a pause in the tension and Alice, convinced she has an overactive imagination, decides to go swimming. Here Tourneur uses a very different technique, relying not on jumps but on the creepiness of shadows and the feeling that something is there, prowling just beyond the light. Again, shadows dominate. She hears a noise, panics and jumps into the swimming pool for safety. The shadows move – are they just the result of the normal dance of light on water? We hear a cat’s growl, the sounds echoing off the cavernous walls and the ceilings. Alice can’t help but scream.

Then the light comes on.

There is no cat, just Irena. This is the payoff, this is the point when Irena transforms from a helpless woman into a feline threat. It is the moment when we start to doubt the intentions of the woman who, until now, was the heroine of the film.

Within a few minutes Tourneur cranks up the tension, wrong foots us creating relief and gives us a false sense of security, then continues to threaten his protagonist (and the audience) until she can’t help but scream. It is an exemplary example of a master of horror knowing exactly when and how to wind the audience up.

Within a few minutes Tourneur cranks up the tension, wrong foots us creating relief and gives us a false sense of security, then continues to threaten his protagonist (and the audience) until she can’t help but scream. It is an exemplary example of a master of horror knowing exactly when and how to wind the audience up.

The Set-Up is all about mystery. We must be told enough so that our imagination can fill in the gaps. It’s about suspension of disbelief to the extent that we totally believe, only then will we become sufficiently excited enough to forget about the world around us and exist entirely in the moment displayed on screen.

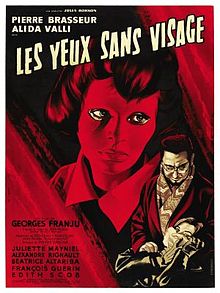

The mystery in Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face lies behind a mask. Edith Scob plays Christiane, a young woman whose face was badly mutilated in a car crash which was her father’s fault. Now she lives in a large house with her father, Docteur Génessier (Pierre Brasseur) and his lover/companion/secretary Louise (Alida Valli). Her boyfriend and her friends think she’s dead and there are times she wishes she were. Her father, a respected and successful plastic surgeon, is wracked with guilt and is determined to repair the damage to his daughter’s face but to do so he needs a living donor so he sends Louise out looking for women with the same facial structure as Christiane so she can kidnap them and bring them back to the doctor. He also experiments on dogs which he keeps caged next to his surgery. The only person to show them any kindness is Christiane as they reflect her own captivity.

The mystery in Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face lies behind a mask. Edith Scob plays Christiane, a young woman whose face was badly mutilated in a car crash which was her father’s fault. Now she lives in a large house with her father, Docteur Génessier (Pierre Brasseur) and his lover/companion/secretary Louise (Alida Valli). Her boyfriend and her friends think she’s dead and there are times she wishes she were. Her father, a respected and successful plastic surgeon, is wracked with guilt and is determined to repair the damage to his daughter’s face but to do so he needs a living donor so he sends Louise out looking for women with the same facial structure as Christiane so she can kidnap them and bring them back to the doctor. He also experiments on dogs which he keeps caged next to his surgery. The only person to show them any kindness is Christiane as they reflect her own captivity.

From the start Franju builds up the mystery of Christiane’s appearance. The kidnappings are presented with an almost detached realism, there is little attempt to build up the apprehension. They are just means to an end. The real focus is Christiane. In the beginning Franju films her from behind, her face turned away from the camera, later she walks through the house wearing her mask.

By doing this Franju uses the same technique as Hitchcock and Tourneur. By placing the focus of the film on one woman, a woman who for some reason we do not know wears a mask, he builds up our anticipation. He is telling us there is a mystery, that something is just not right, and he makes us wait. In one extraordinary scene Christiane absentmindedly wanders the rooms, her mask vacant and unmoving yet we still get an overwhelming sense of her loneliness. So much of this woman’s character is revealed to us through her body movements and her eyes, nothing more, yet the one thing we are not told is why.

The reveal is horrific and we get a glimpse of the physical pain that this woman is experiencing which underpins and intensifies the psychological damage that has become obvious. But Franju is not content to end it here. Like a relieved Alice getting onto the bus in Cat People, Christiane has a fleeting moment of relief but this is quickly swept away and she is plunged into a deeper hell which finally breaks her.

These moments of horror and the way filmmakers use the tricks of their trade to present them to us have existed since the silent era. In the 1925 film The Phantom of the Opera, Mary Philbin, who acts as a surrogate for the audience and rips off the Phantom’s mask; the structure I’ve described was already in play two years before the Jazz Singer told us “we ‘ain’t heard nothing yet!” What these examples show us is that the payoff can’t just happen, it must happen at the right moment. But what is the right moment? Why do these classic films work but Aliens Vs Predator: Requiem doesn’t? I would suggest that there are two points where the director usually places the reveal in order to get the very best effect. Firstly, the most obvious moment is after an extended period of built up anticipation. The director must slowly and effectively crank up the tension until the audience can stand no more. Once this has been achieved they have a number of options – to wrongfoot the audience as Tourneur does with the bus, or to fulfill our collective need and scare us out of our wits.

These moments of horror and the way filmmakers use the tricks of their trade to present them to us have existed since the silent era. In the 1925 film The Phantom of the Opera, Mary Philbin, who acts as a surrogate for the audience and rips off the Phantom’s mask; the structure I’ve described was already in play two years before the Jazz Singer told us “we ‘ain’t heard nothing yet!” What these examples show us is that the payoff can’t just happen, it must happen at the right moment. But what is the right moment? Why do these classic films work but Aliens Vs Predator: Requiem doesn’t? I would suggest that there are two points where the director usually places the reveal in order to get the very best effect. Firstly, the most obvious moment is after an extended period of built up anticipation. The director must slowly and effectively crank up the tension until the audience can stand no more. Once this has been achieved they have a number of options – to wrongfoot the audience as Tourneur does with the bus, or to fulfill our collective need and scare us out of our wits.

This can sometimes change the course of a whole movie. In Jaws, Steven Spielberg observed that, in his original cut, the first appearance of the shark got a huge scream from the preview audience but when he added the shot of Ben Gardner’s head floating out of the sunken boat, the audience reaction was quite different. This got a bigger reaction and the impact of the Shark was lessened. From this Spielberg surmised that there could only be one major scare in a movie. I don’t think this is necessarily true because there are a number of films which have more than one moment of shock and terror. For example, Psycho has two; the first is the famed shower scene and the second is the final revealing of Mrs Bates at the film’s climax. In Alien we have the face hugger bursting from the Alien egg and wrapping itself around John Hurt’s face and also the final showdown between Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) and the creature of the title. This is not a sudden shock like Psycho, it is a moment when we are sitting on the very edge of our seats, our whole body rigid with tension and stress.

This can sometimes change the course of a whole movie. In Jaws, Steven Spielberg observed that, in his original cut, the first appearance of the shark got a huge scream from the preview audience but when he added the shot of Ben Gardner’s head floating out of the sunken boat, the audience reaction was quite different. This got a bigger reaction and the impact of the Shark was lessened. From this Spielberg surmised that there could only be one major scare in a movie. I don’t think this is necessarily true because there are a number of films which have more than one moment of shock and terror. For example, Psycho has two; the first is the famed shower scene and the second is the final revealing of Mrs Bates at the film’s climax. In Alien we have the face hugger bursting from the Alien egg and wrapping itself around John Hurt’s face and also the final showdown between Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) and the creature of the title. This is not a sudden shock like Psycho, it is a moment when we are sitting on the very edge of our seats, our whole body rigid with tension and stress.

The secret is not to limit these scenes to singular moments but to take the time to build that anticipation. That is the key. If it is rushed then the pay-off is diminished. This is not to say that a well worked build-up guarantees a suitable payoff. Think of M. Night Shyamalan ‘s The Happening (or Signs or The Lady In The Water). This is simply not the case but without it the payoff will never have the impact it could have.

This is the lesson for prospective horror film-makers. Take the time to tell the story right. Do not underestimate the audience. The problem with many sequels is that the filmmakers believe they understand the reason the original film was successful but they don’t always actually understand the reason the film they are attempting to follow worked in the first place. Yes, we loved the Predator and the Aliens but they were successful because the people making them knew the basic rules – they knew how to set-up the pay-off, they knew how to play the game with the audience. The same goes for Freddy Krueger who was scary in the original A Nightmare on Elm Street but not so in the sequel which failed simply because there was too much of him too soon. As in many films, the reason the monster is so effective is because we don’t see it. This might not seem applicable in a sequel as we have already seen the monster in the first film but it is still relevant. In order to increase the audience pleasure, you have make them want it. Less is invariably more

So, the secret? Know how to play with the audience, when to take them to the edge and when to pull them back. We want to see the monster but the game is much more interesting. Does this apply to every horror film or suspenseful thriller? Well, yes and no. There are no ‘shower scene’ moments in Silence of the Lambs but it does not stop the film from being highly effective, maintaining a sense of unease throughout. The same can be said of The Exorcist which has a number of stand-out moments but none that would specifically meet the criteria mentioned here. What it does is continuously undermine the audience’s sense of comfort until the very final moments when we are left gasping for air. Does that mean that neither of these films are not as good as some of the examples mention previously? Absolutely not, these are two of the greatest examples of the horror/suspense genres. In fact, the same rules do apply only they are not focused on individual moments of pay-off, instead they are structured around a constant and consistent momentum and the pay-off comes at the very end.

So, the secret? Know how to play with the audience, when to take them to the edge and when to pull them back. We want to see the monster but the game is much more interesting. Does this apply to every horror film or suspenseful thriller? Well, yes and no. There are no ‘shower scene’ moments in Silence of the Lambs but it does not stop the film from being highly effective, maintaining a sense of unease throughout. The same can be said of The Exorcist which has a number of stand-out moments but none that would specifically meet the criteria mentioned here. What it does is continuously undermine the audience’s sense of comfort until the very final moments when we are left gasping for air. Does that mean that neither of these films are not as good as some of the examples mention previously? Absolutely not, these are two of the greatest examples of the horror/suspense genres. In fact, the same rules do apply only they are not focused on individual moments of pay-off, instead they are structured around a constant and consistent momentum and the pay-off comes at the very end.

Ultimately, what it all comes down to is that the director and writer has to have a sense of fun and are confident and capable enough in their ability to translate this fun into film language. This means being able to constantly anticipate what the audience really wants from a horror and a suspense film and that is, very simply and obviously, instil feelings of horror and suspense in the audience. We need to want it and we need to earn it because then it is all the more fun.