Angel’s Egg (1985).

Over thirty years ago director Mamoru Oshii and artist Yoshitaka Amano created a seventy-one minute short film with little plot, even less dialogue, and with such little broader appeal that it has more or less fallen into obscurity. On top of all of that, it’s incredibly hard to find a copy of it to begin with. So, why talk about it?

Because the director’s name may be familiar. Oshii would go on, a decade later, to direct Ghost in the Shell, one of the most famous science fiction films of all time. Close to two decades later, he would create Innocence, Ghost in the Shell‘s pseudo-sequel. Angel’s Egg was not Oshii’s directorial debut; that honour belongs to the two Urusei Yatsura films that came as a result of his work on the television series of the same name. He would later depart the animation studio at which he got his start, Studio Pierrot, and proceed to make Angel’s Egg, or Tenshi no Tamago. Oshii and Amano aren’t the only two notable names attached to this strange, cryptic, symbolic tale. One of its producers, Toshio Suzuki, would go on to form Studio Ghibli with Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata.

Angel’s Egg became one of the early examples of what’s commonly known in Japanese animation as OVA’s, or Original Video Animation. These are generally movies shorter in length and released direct to video or on television. Conceptualised with Amano and written solely by himself, two things happened upon the film’s release; Oshii didn’t receive work for the three years that followed, and in that three years it had been appropriated without permission by another production company and made into the film In the Aftermath. These are bitter memories for the beloved filmmaker.

The film itself is a hard sell for anyone not looking to familiarise themselves with Oshii’s body of work – an impossible sell, maybe. Even its director is unsure of what it’s about, though there is a distinct religious quality to it, and an existentialism that alludes to the loss of belief that Oshii is noted to have experienced at a similar time in his life. So little happens in the film’s hour-and-change length, but if any more did then its artistic allure might start to wane. That allure is a combination of moody shadow, architecture that appears as though it might collapse at the slightest turn of the wind, and a pair of characters with bright white hair that stands out in the blacks and dark blues of their surroundings.

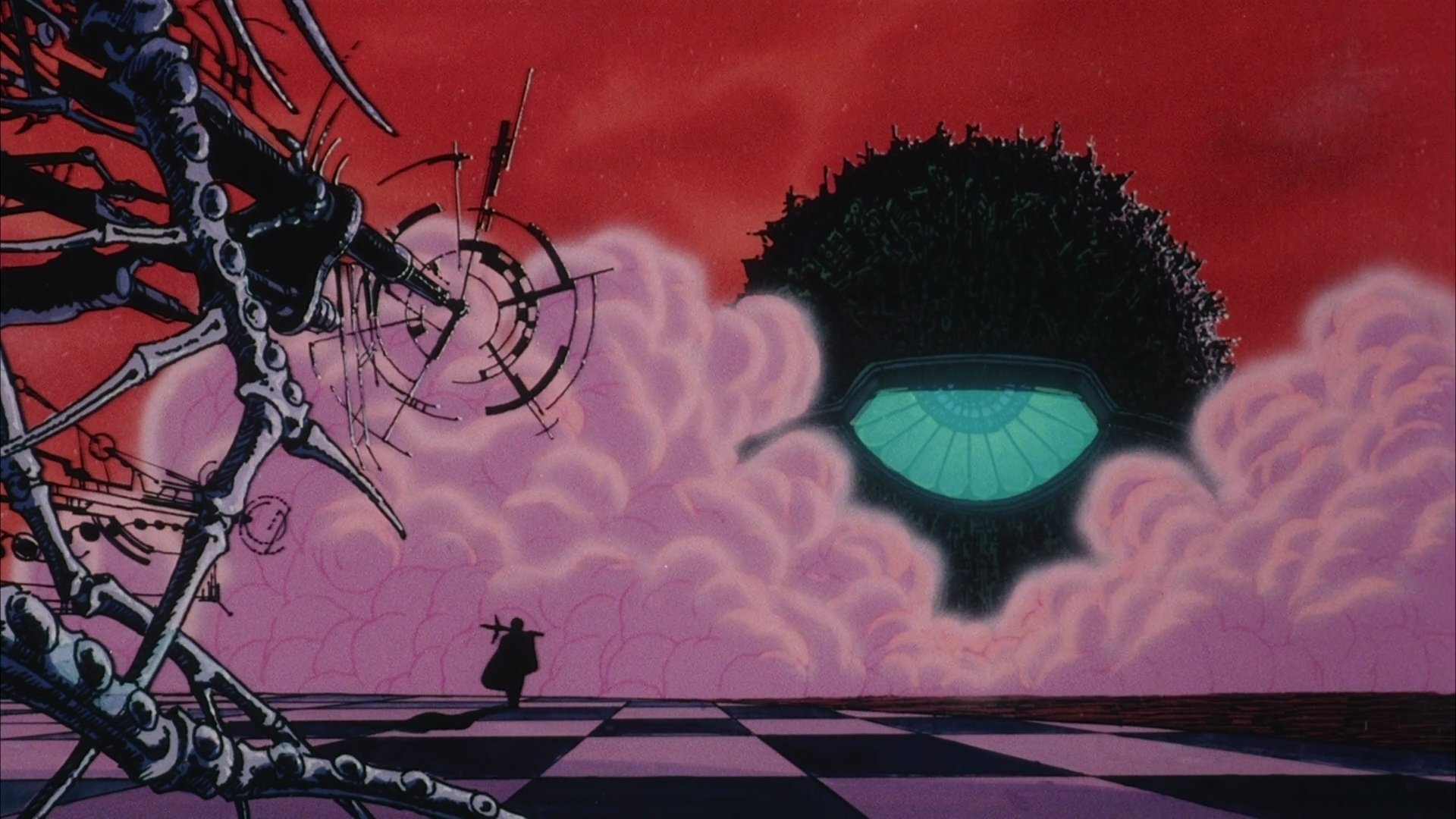

Angel’s Egg takes place in a dystopian fantasy world, and its bleak visuals are evocative of the aesthetic found in the design work of H.R. Giger; it’s impossible to look at this and not be reminded of Ridley Scott’s masterpiece, six years old at the time of the OVA’s release. Those familiar with Ghost in the Shell – and I expect that no one who comes to this now won’t be – will immediately recognise the photo-realistic character design, though the backgrounds and the colour palette makes the later film seem positively Utopian.

We’re first introduced to a young man carrying a staff of sorts shaped like a cross as he observes a strange vessel rising from the ocean adorned with statues of human appearance. The boy is never given a name. We’re soon after introduced to a young girl who carries an egg with her, clutching it the same way an expectant mother might clutch her pregnant belly. The girl, too is never given a name. She scavenges through the gothic, Art Nouveau-inspired abandoned city near the derelict building she inhabits. Soon she comes into contact with the boy. She’s as frightened by him as she is by the strange, soldier-like fishermen who march through the city throwing spears at the shadows of giant fish that drift across broken buildings.

Soon enough, the adolescent boy and the girl become travelling companions. There’s so little dialogue to accompany the grandiose artwork, and an absence of plot that can make for a menial mid-section regardless of the undeniable visual splendour. The girl wants to hatch the egg, but won’t tell the boy what’s inside of it. The boy tells the story of Noah’s Ark in the film’s most dialogue-dense sequence, but questions whether it, they, or anything at all even really exist. It rains from start to finish; The boy’s biblical monologue is not without merit. The boy talks about memory the way we might talk about a mostly forgotten dream, but the memory is proven to be true when the girl shows him the horrifying, fossilised skeleton of the same giant bird he speaks of.

So rarely does a film make so little sense but suffer so little for it, inviting speculation with little to form any one theory. Angel’s Egg creates a strange kind of trance, and demands the same eye for detail that’s required of all of Oshii’s work. Yoshihiro Kanno’s score and Amano’s art lead a hauntingly dark fable about two characters in an empty world trying to make sense of their amnesia and their existence. The editing is exquisite, with moments of abrupt horror and others of a curiously bewildering ilk. Its lack of plot does not equate to a lack of stakes, and the world feels both intimidatingly large and uncomfortably small at the same time. When the girl wakes from her slumber to an unpleasant discovery, her anguish comes after a moment of silent pause. It’s a startling, punctuating example of Oshii’s talent.

No one who isn’t familiar with the works of Oshii or who doesn’t harbour a curiosity for the anime of the eighties and nineties needs to seek this film out. It would, I think, be a perfect bonus feature to accompany a future home release of Ghost in the Shell, though perhaps that’s wishful thinking. There’s a sense that this is the work of a creator with a vision, even if at this particular point in time that vision hadn’t quite become whole. It’s an artistic endeavour that is easy to appreciate, but will prove difficult to love for many. And yet it’s a piece of Oshii’s body of work that simply cannot be ignored.

Film ’89 Verdict – 8/10