Cinema Paradiso (1988).

Cinema Paradiso is about many things; the formative years of a young boy and how he grows up in a single-parent family to become a successful film director; the relationship between a young man at the start of his life and an old man who has survived two world wars and the devastation that came with them; a love story between a young man and young woman; a village, recovering from the war, struggling with poverty, politics and the changing times of society. It is all these things certainly, but it is also at its heart a love song to cinema; how it inspires people, defines them, brings them together and reflects the times we live in. It is about cinema itself. All these elements combine to make a beautiful poem using images of light instead of words, and music instead of rhyme.

It starts with a phone call answered by a stranger who assumes the identity of someone she is not. She doesn’t do this to deceive but to avoid hurting and confusing the old woman who is calling. The old woman is Maria Di Vita and she is trying to contact her son to tell him of the death of an old man he hasn’t seen in over 30 years. Later that evening Salvatore Di Vita returns home from work to be told of the conversation, as he hears the news a subtle change comes to his face, he did not expect this news and hadn’t thought of this man for many years. He turns over in bed and we are taken back to his childhood in the small Sicilian village of Giancaldo.

It’s a few years after the war and Giancaldo is a broken village. It’s a place of poverty where work is scarce, and when it is sometimes available, men are refused because of their political affiliations. At the centre of the town is the square, an open space where people buy and sell, catch buses and queue for work. It is the very heart of this small community. At night, as midnight chimes and when most decent people are at home sleeping, it becomes the possession of the local madman who chases everyone out barking at them ‘It’s mine. The square is mine.’ This madman is just as much a part of this community as anyone else.

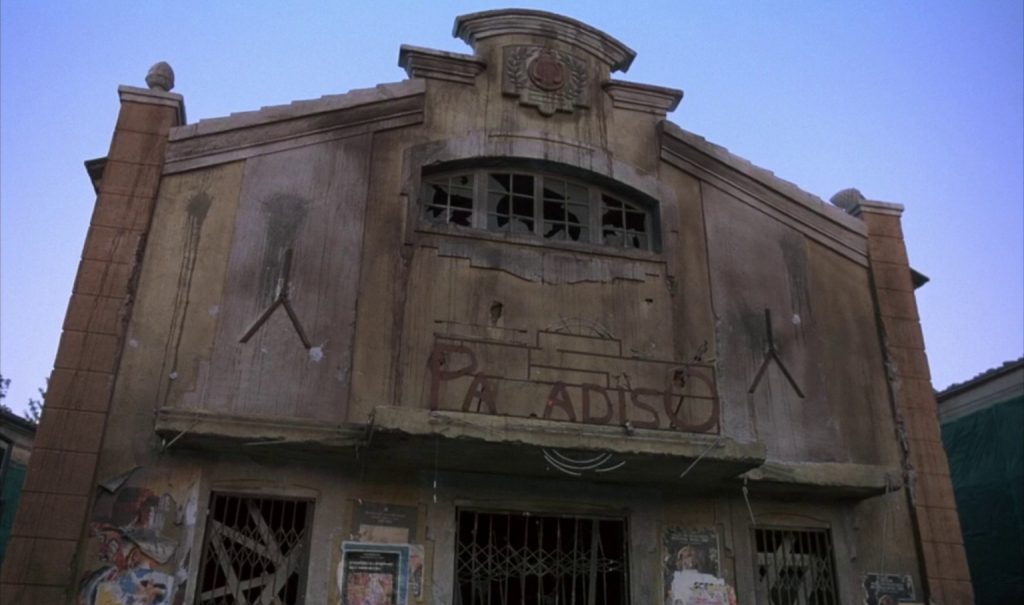

At the top of the square, dominating the area is the cinema – the only place in the village where people can meet, talk and be entertained. It is very much the cultural centre of Giancaldo. The name of the cinema is Cinema Paradiso and people go there to forget their troubles and, in those days of limited communication, to be reassured that the rest of the world exists, that life goes on outside the limits of Giancaldo.

The young Salvatore – Toto – is an altar boy who has little interest in anything apart from the movies, and luckily for him, he knows the projectionist, Alfredo. Alfredo is a gruff old man who has lived in the village all his life, he knows everyone, and everyone knows him. He has no education and little prospects. However, from his little seat in the cramped confines of the projection booth, he is the alchemist that produces moving pictures; he operates the machinery which manipulates the light and creates the images on the screen. In doing so he holds an important position in the town, even though, confined as he is to the booth, he can never partake in the communal experience he oversees.

Toto’s mother can’t afford to let him go to the cinema as often as he does. In fact, at one point, Toto uses the money meant for bread to buy a ticket. When admonished, it’s Alfredo who comes to the rescue and each time Toto is banned from the projection room he works out a way to get back in, often manipulating and black-mailing Alfredo.

The spine of Cinema Paradiso is this relationship between this mischievous youngster and the old man. Slowly they get to know each other more deeply, sharing confidences and confessions. Toto’s father hasn’t returned home from fighting in Russia, and even though his mother refuses to believe he is dead, we know there is little chance of him ever returning. For Toto, his absent father is replaced by a very reluctant Alfredo who adopts the patriarchal role that Toto desperately needs.

For Toto, there is very little in the village that interests him other than the movies. They catch his imagination and provide him with a creative outlet that his circumstances have limited. His father is a figure who seems less real than his celluloid heroes. He exists in only one photograph, whereas Humphrey Bogart lives in countless images on the silver screen and in the tiny pieces of film that scatter the booth. Like any child, Toto needs an outlet to express himself, and also a means to experience the world, and it’s these near-mythical characters that dominate and entertain him. Alfredo is the gatekeeper and the guide through this magical world.

The colour of Cinema Paradiso comes from the village itself and the people who inhabit it. As the years pass, we see the characters age and we begin to form a bond with them. The Priest who insists on watching the films first so he and Alfredo can edit out any kissing or other romantic moments (‘I’ve been coming here 20 years and I still haven’t seen anyone kiss,’ someone exclaims at one point); the man on the balcony who spits on the cinema-goers below him; the man who just wants to sleep but is always the butt of practical jokes. All of these characters are intricate stitches in the colourful and elaborate tapestry you are watching. It is obvious a great deal of love and affection has gone into creating and playing these roles.

Change happens slowly but as the years pass, they do occur – hair gets greyer, people meet, fall in love and get married; the films get more risqué, as the influence of the ‘50s overpowers the influence of the church. We see beauty and tragedy. Indeed, one of the best and most famous scenes in the film is followed by the most terrifying and tragic:

The cinema is full and there are still many people outside who want to come in. They call up to Alfredo to do something for them. Alfredo smiles knowingly and asks Toto if they should satisfy the crowd’s appetite and Toto readily agrees. The old man adjusts a mirror on the projector and an image appears on the wall. Toto’s eyes widen in excitement and wonder, as the mirror is moved further, and this image moves along the wall. It crosses the room before appearing full-sized on the wall of the building across the square. The crowd cheers, the music soars and the priest, spying an opportunity to make some money, sends someone out to sell tickets. The crowd, of course, are having none of it. It’s a perfect little moment where the magic of the movies is writ large, beautifully and elegantly.

Then the image breaks up. Alfredo turns to the projection to see that notoriously flammable nitrate film stock has caught fire. The wonderful moment is brought to a shuddering end and Toto, too young to work but the only person other than Alfredo who knows how to operate the machinery, takes over the role of projectionist.

There is much darkness below the surface, but it is presented from the point of view of a child and so this is sometimes obscure. Take the scene when Toto and his mother return home after hearing his father has died in Russia. Maria is devastated and so is Toto, but mostly because he knows he should be. He never knew his father beyond the abstract, and as they walk home together, the upset child spots a large poster for Gone With The Wind. Suddenly his hurt is gone, replaced by a smile of genuine pleasure. He is distracted by the power of that beautiful poster, of Clarke Gable and Vivien Leigh in an embrace. As adults, we feel the hurt of the mother and the charm of the innocent.

Religion dominates this little town. When we are introduced to the young Toto, he is an altar boy. Not a very good one as he keeps falling asleep, which the local vet explains is because the boy is not eating enough. One of the themes of Cinema Paradiso is the slow decline of Catholicism as the decades change from the recovery of the late ‘40s and into the decadence of the ‘60s. There is a moment at the start of the film when, after the priest and Toto change their clothes and leave the church, the wind blows open the wardrobe and we see a statue of the Virgin Mary hiding away, but ever present. Throughout the film, this is a recurring motif.

The years continue to pass. As Alfredo puts it: ‘Living here day by day, you think it’s the centre of the world. You believe nothing will ever change. Then you leave: a year, two years. When you come back, everything’s changed. The thread’s broken. What you came to find isn’t there.’

As Toto becomes a teenager, he discovers girls and filmmaking, one time secretly filming the girl of his dreams, Elena. The most romantic scene in the film is also one of the most playful. Elena has been away for the summer; Toto is still working as a projectionist showing films outdoors during the hot summer. He lies on his back, wishing summer would end quickly so he can be with his girl again. If this were a film, he muses, there would be a cut accompanied by a clap of thunder and rain and summer would be no more. Suddenly there is indeed a clap of thunder and the rain pours. As the audience rushes for cover, Toto remains on the ground happy that his wishes have come true. We look down on him in close-up, his eyes closed, a broad smile on his face, and suddenly above him appears Elena who reaches down and kisses him – the fantasy of film has become reality.

The power of film is, of course, this very fantasy – it takes elements of reality and compresses them, reinterprets them, shuffles them to create something which affects us emotionally, intellectually and sometimes physically. We can experience the fantastical in a way that is very personal and the more personal our experience the more we are affected by it. This is the lesson of the final scene of Cinema Paradiso. Alone in the cinema, the older Salvatore watches a compilation of all the kisses that were cut from the hundreds of films he grew up with. Each moment a fantasy that can only live on the silver screen, touching him in a way so personal and intimate that he can’t help but cry. And neither can we, as we have spent the last two hours getting to know and love these people.

There is a moment when Toto is now a young man and is leaving Giancarldo, when Alfredo grabs him and beseeches him never to come back and to never even look back. ‘Don’t give in to nostalgia. Forget us all,’ he says with passion. He knows the reality of this small town with its limited prospects. He understands that this young lad, whom he has cared for and loved for so many years, needs to escape and to find his own place in the world. ‘Whatever you end up doing,’ he says, ‘Love it.’

This may seem a little odd in a film which is so steeped in nostalgia and the reason becomes clearer in the original and director’s cuts. Giuseppe Tornatore’s original cut was 155 minutes and much of it followed Toto’s return to the village, which has now become a modern town. He meets Elena again and tries to recapture that feeling they had once shared. But it is impossible. The past is past, and times have changed too much and too far. Alfredo was right. Even though his words seemed harsh at the time, he was always right.

When it was initially shown to audiences, the film was not well received. It was then picked up by Harvey Weinstein’s company Miramax. Weinstein, famous for re-editing movies he had bought, recognised that the director’s cut was quite downbeat and exorcised many of the scenes in the present day that did not serve the theme of nostalgia. In many ways, Weinstein was correct, and the newly edited version became an international hit winning many awards including Best Foreign Film at the Oscars, and grossing over $12million in the US alone.

To me, the various versions are very different films. I fell in love with the Weinstein (International) version as it is a beautiful tribute to childhood and growing up, but the Director’s Cut, which is almost three hours long, is equally as interesting. It provides a very different take on nostalgia. It tells us that we can’t go back, just as Alfredo warned. The International version revels in Nostalgia and I can understand why some people dislike it for that, but the Director’s version undercuts that simplicity and resonates very differently. I must confess, although I appreciate the two versions, whenever I watch Cinema Paradiso, and I do seem to watch it at least once a year, I usually watch the International Version. This version, the fusion between the past and the cinema is greater and for a cinephile like me, it is irresistible.

Cinema Paradiso is probably my favourite film for this reason. I am always open to believing in film, but films like this just want me to believe more. It reinforces my feelings for this medium and each time I see it I want to see it more.

The music by the maestro Ennio Morricone has become especially famous and many know it who have never even seen the film. The Love Theme has had lyrics added to it and has become a hit on Classic Music radio. With its soaring themes and beautiful simplicity, it is probably my favourite soundtrack of all time, no doubt linked to my love of the film.

The final scene, which I have already alluded to, is one of the greatest moments in cinema history because of its devotion to cinema history. It celebrates this wonderful medium in a way that few other films have ever managed. Yes, Cinema Paradiso presents us with a romanticised past, however, I am perfectly alright with that. It makes me feel good, it makes me feel wonder and joy at this most fantastic of mediums, and isn’t that one of the powers of cinema? To make us feel. And Cinema Paradiso, despite all its layers and themes, is essentially about the power and magic of the movies.

Film’89 Verdict – 10/10

Cinema Paradiso is available on Blu-Ray in the U.K. courtesy of Arrow Video.