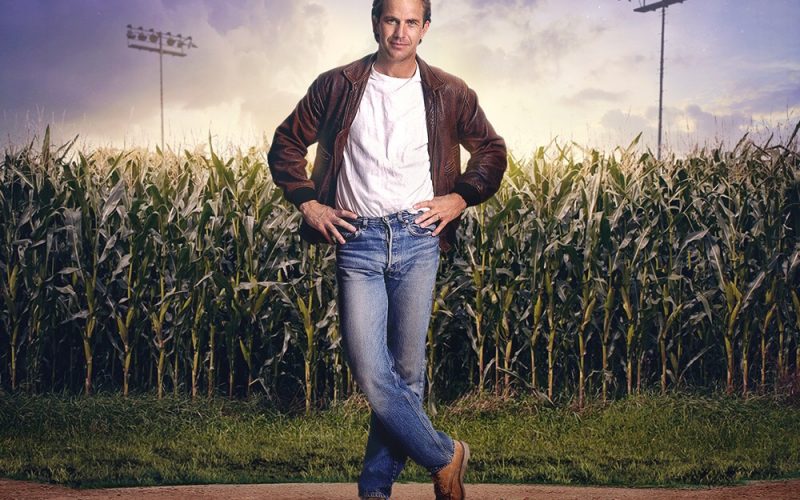

Field of Dreams (1989).

It has often been said in the field of entertainment that there’s nothing original any more, especially when discussing Hollywood movies. Take any film in the last 100 years and there’ll be obvious debts to those preceding them. Even at the dawn of film the lexicon of cinema came from existing media – books, the theatre etc, and possibly the most influential book of all, the Bible. In this respect, Field of Dreams is no exception. Throughout its 107 minute running time, there are numerous parallels with other great films, some intentionally and others because the film adheres to a particular and well established formula. It also uses religion and spirituality in a way that, whilst not new, is no less interesting. What makes it a great film is not necessarily it’s originality, but how it uses existing norms to tell its own story, one that still resonates thirty years after its release.

The opening scenes for example, are reminiscent of the beginning of Citizen Kane. We start with a montage of someone’s life, from birth to death, and then hear the words that will serve as a spring-board for the rest of the film. In Kane we see a close-up of the great man’s moustachioed mouth as he utters his last words, ‘Rosebud’. In Field of Dreams, the words are carried on the evening breeze, to Kevin Costner’s Ray Kinsella, as he walks through his corn field.

We aren’t told where the voice comes from, although judging by the fact that only Ray hears it, it may all be in his head. The voice is almost a whisper yet seemingly loud enough to carry across the corn field – ‘If you build it, he will come’. We aren’t told who ‘he’ is or what needs to be built. This is a mystery which will carry the narrative through its various stages. This unorthodox beginning introduces the themes that will be touched upon throughout the film – mystery, madness, fatherhood, baseball, and of course, dreams.

Later that night, his mind and heart racing as he tries to make sense of the voice, Ray looks out at his field and imagines a baseball field there. He knows what he has to build and it fills him so completely that he can’t let it go. In this respect, Kinsella mirrors Roy Neary (Richard Dreyfus) in Close Encounters of the Third Kind. He’s been given a glimpse of the dream but not enough for him to understand exactly what it is he’s searching for, and yet he’s completely consumed by the thought of it. He doesn’t know where it came from – nor does he know why – he only knows he MUST follow it through. Like Neary, Kinsella is an everyman caught up in the most remarkable of circumstances. He is the link between the audience and the dream, and we want him to follow this yellow brick road and see where it leads. We share his fear at the start of the journey – a fear of plunging into the unknown – yet at the same time we also fear not taking the plunge.

One of the most remarkable characters is Ray’s wife Annie, played by Amy Madigan. She knows how much it means to him and backs him all the way, later shielding him from the extent of the financial troubles the baseball diamond has caused them. She has both humour and concern, and at one point even compares her husband’s mystery with Charles Foster Kane’s Rosebud. This is of course the opposite of Neary’s wife Ronnie (Teri Garr) who leaves Roy to his obsession and disappears from the second half of Close Encounters. This is also indicative of the tone of the two movies. Field of Dreams aims for a more emotional story than Close Encounters, which focuses more on the consequences of the obsession and waits until the climax to deliver its emotional wallop.

As Ray builds the diamond, he tells his daughter Karin (Gaby Hoffmann), stories of the Chicago White Sox baseball team and their fall from grace in the 1919 World Series in which eight players were convicted of throwing the championship. The players were banned from ever playing again. One of the eight was a hero to Ray’s father, ‘Shoeless’ Joe Jackson. Ray, like his father, believes Joe to have been innocent as his performance was unparalleled in the series – how could someone who played so well throughout the World Series be guilty of throwing games? Throughout the film Ray tells of his biggest fear – becoming his father – yet here, without realising it, he’s following in his father’s footsteps; passing on to Karin the same ideas, belief and passion that his father passed on to him.

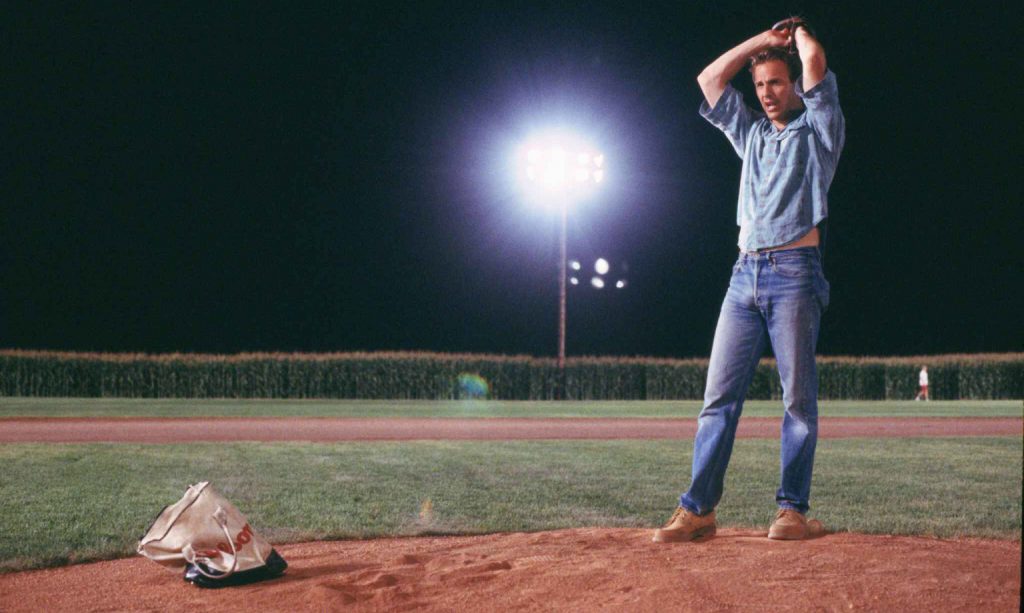

Once the diamond is complete, the waiting beginnings. The bills pile up and the seasons pass. Then one evening Karin, who has been looking out the window, interrupts her parents to tell them ‘Daddy, there’s a man on your lawn.’ The man is the late Shoeless Joe played by Ray Liotta. ‘Are you a ghost?’ asks Karin. ‘What do you think?’ he replies evasively. There’s a definite religious allegory at work here. The religion is baseball and we have a figure, revered by both Ray and his father, being resurrected. Of course, Jackson is not here to save the world but ultimately to save Ray. Jackson asks if ‘This is Heaven?’ to which Ray replies ‘No, It’s Iowa’. Maybe heaven does exist on earth. But this is only the beginning of the adventure. The voice returns, this time telling Ray to ‘Ease his Pain’.

Field of Dreams follows this pattern; Ray is once more confused and a little angry and yet in another moment of (divine?) inspiration, he realises what the voice wants and soon he’s on the road to talk to his childhood hero – the author Terrence Mann (James Earl Jones).

Terrence Mann represents the sixties, a time when there was a feeling that anything was possible despite, and possibly because of, the problems people were confronting at the time. It’s also when Ray and his father stopped speaking (Ray claims he was emboldened to rebel against his father after reading a Terrence Mann novel). Mann is disillusioned by the past, by the promise of the sixties that were never fulfilled. Whereas Kinsella views the decade through the blurred lens of the nostalgia of youth, Mann believes that it was a time when people stopped taking responsibility for their own actions and started to look to others for inspiration, others like him.

The scenes between Ray and Mann provide humour that is contrasted with the growing precariousness of the future of the farm back home. Ray convinces Mann to accompany him by sticking his finger in his coat pocket and pretending it’s a gun; whilst at home Annie’s brother, who, along with his partners has bought the farm’s mortgage off the bank, is threatening to foreclose and take the farm, effectively pointing a real gun at the family.

Of course, the very nature of Field of Dreams‘ core is a message of optimism – we know that the family will be OK, we know that the farm will be saved from the bank and we know that the dream will become real. Yet at this point we still don’t know what that dream is exactly.

When Ray slips into a different time without even realising it, we are never told how. Neither are we told how another character can skip from the 1930s into the present. If you’re properly along for the ride and Field of Dreams has suitably set out its stall, then these aren’t questions that really need an answer.

At the end of the film we realise we’ve been looking in the wrong direction. Each step has been designed like some sleight of hand, taking our eyes away from the obvious, and instead looking at what the director wants us to see. Ultimately, Field of Dreams isn’t about the fantastical but the more mundane – the relationship between a father and son. The achievement of the film is that even though we’ve been treated to a fairly big MacGuffin, we’ve still been given all the information we need for the climax to have the emotional punch it requires. It’s a technique used repeatedly by Alfred Hitchcock and many others. As Glinda the Good Witch says at the end of The Wizard of Oz, the answer was there all along. Sometimes it isn’t obvious to the protagonists, as with the reporter in Citizen Kane who laments that he would never find out what the word ‘Rosebud’ meant only a few seconds before the audience are shown the burning sledge. Other times it needs someone to point out the truth. As Glinda does in Oz, Shoeless Joe Jackson does in Field of Dreams,‘It was you Ray, it was always you’.

Field of Dreams is a film that adheres to a tried and tested formula and has themes which have been explored many times before and since. It’s technique comes from classical cinema and it does little to expand the language of film. But that isn’t the point. What Field of Dreams aims to do and completely succeeds at doing is moving its audience and tugging at heart strings by utilising long established film language beautifully. It’s a film for dreamers, and in my experience, lovers of film are by their very nature dreamers. Like the very best works of directors like Frank Capra, what writer/director Phil Alden Robinson has achieved with Field of Dreams is to meld the magic of film, playing on the power of nostalgia for ‘better times’ and the natural human desire to connect with the past and those things and people we’ve loved and lost to create a magical piece of cinema that transcends time, breaks through the confines of genre and stands three decades on as one of the most beautiful pieces of work ever committed to film.

Film ‘89 Verdict – 10/10