Grand Prix (1966).

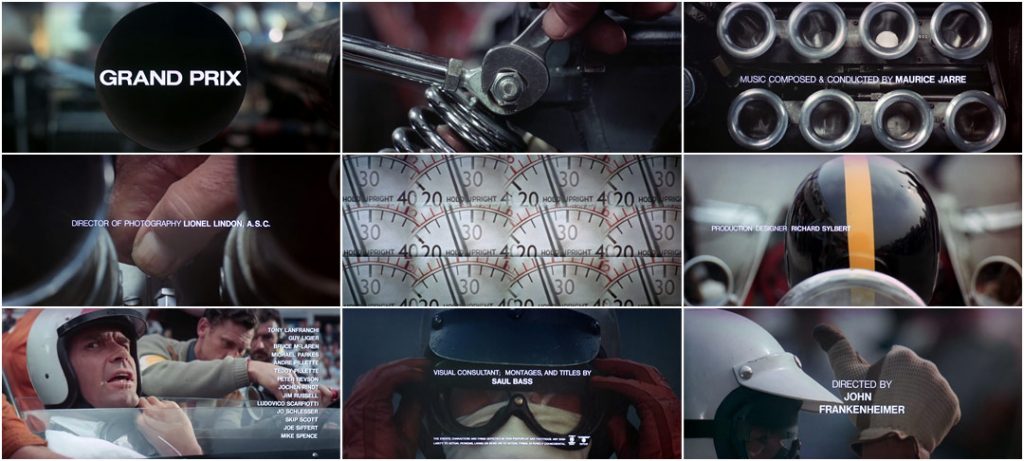

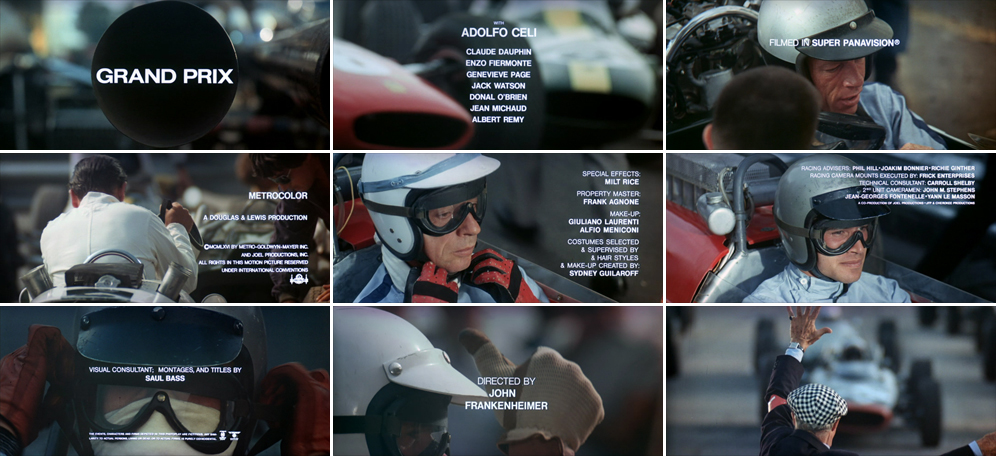

John Frankenheimer’s epic 1966 Formula 1 racing drama opens with a four and a half minute title sequence that consists of a chain of shots of exhausts, tyres, cylinders, dials, throttles being adjusted and drivers sat in their cars on the starting grid at the famous Monaco Grand Prix circuit. Frankenheimer employs great use of split-screen photography to mix up the close-up shots coupled with the roar of revving engines before we are thrown headlong into the film’s opening race.

This brilliantly edited title sequence, by none other than the legendary Saul Bass, is an almost pornographic celebration of all things mechanical and automotive and a firm indicator that this film has a director behind the wheel who is more than fit for purpose. Frankenheimer was well known for his love of cars and racing and was the perfect choice to film an almost three hour study of the thrills, politics, culture and danger of this incredible sport. It would be filmed alongside the 1966/67 Formula 1 season and would follow four fictitious drivers played by James Garner, Yves Montand, Brian Bedford and Antonio Sabato. Famous real life drivers would play supporting roles throughout.

The drivers and supporting characters is where the fiction would end as the racing teams, locations, tracks and cars would all be very much real (although Formula 3 cars stood in for the Formula 1 cars used in real life to keep the production costs down). It follows our drivers as they make their way through the season and their interactions both on the track and off. Personal relationships are firmly interwoven and although some of the more melodramatic elements are a little ham-fisted in places, on the whole we are given what feels like a very honest portrayal of the incredible camaraderie within the extended Formula 1 family of drivers, their own families, the crew and team owners.

Garner’s American driver, Pete Aron is looking for his first championship win and gives a more than solid central performance as the man doggedly chasing the current champion, Yves Montand’s coolly disciplined and experienced Frenchman, Jean-Pierre Sarti. Bedford’s Brit racer, Scott Stoddard’s story arc follows an eerily similar one to that would nearly kill Niki Lauder in real life 10 years later. Former Bond villain, Adolfo Celi would play über bastard and Ferrari boss Agostini Manetta. How the then real life Ferrari boss Enzo Ferrari allowed such a raw and cutting portrayal of the man who’s team would, in real life, drive seven drivers to their deaths in the 50’s and 60’s is quite amazing and was a very brave move indeed.

No discussion of Grand Prix would be complete without an analysis of the film’s staggering technical aspects and have no doubt, this is one of the most technically astounding films ever committed to the big screen. The film strikes a perfect balance of drama and racing action and the shot-for-real racing makes up a considerable proportion of the near three hour run-time. The film would nab three Oscar’s for its technical achievements.

Frankenheimer had his crew construct a series of never before seen camera mounts which would be attached to the cars and allow for 180 degree panning from a front-on shot of the driver to a driver’s point of view of the on-coming track. This places the viewer right in the cockpit and the sense of speed and danger is palpable. The aerial and crane photography is also superb and makes the most of the snaking courses. Not a single process shot is used. All the racing is done for real.

James Garner, at the time one of Hollywood’s biggest names and earners, did all his own driving. He’d frequently match and often best the film’s professional drivers in races held in between shooting. Seeing a major star on screen behind the wheel driving at speeds often reaching 150mph is something that gives the film a verisimilitude that few films have ever matched save for Steve McQueen’s own passion project Le Mans (1971).

The aforementioned sense of realism includes aspects of the real-life courses that seem almost far fetched. In one race on Belgium’s Spa Francorchamps course, our drivers hit a veritable wall of rain that comes from nowhere and causes carnage. This was a realistic portrayal of the circuit’s micro-climates and a well implemented dramatic aspect that racing fans would no doubt (pardon the pun) lap up.

The absurd danger of the Italian circuit at Monza with its high banking corners was how the course looked back then and this would be the last time the course would be seen in such a form before significant changes were brought in to prevent drivers flying off the track. Again the film has an eerie prescience in that this race is the one that has two of our drivers vying for the championship, one determined to prove himself, the other resigned to the pressures placed upon himself by his team’s owner. The shocking conclusion to this race would be seen in a similarly shocking and wholly real tragedy when Ayrton Senna lost his life at Imola, Italy almost 30 years later. His death also attributed to a similar degree of pressure and doubt that Sarti finds himself in here.

This aspect of the film’s portrayal of the dangers of the sport is its key theme throughout and what lends Grand Prix an almost documentary edge. The ’66/’67 season was the last one where drivers were racing without properly considered safety precautions. Prior to the big changes brought into the sport by those championing driver safety such as Jackie Stewart, drivers were losing their lives on an alarmingly frequent basis. The film takes time to assess why the drivers take such risks, what drives them to do so and why death was such an accepted inevitability of the sport at that time. By the film’s close we are left with one of our four drivers walking the track post-race, lamenting the death of a friend, a brother, in this most close knit of families.

The sport would be forever changed and the deaths would be drastically reduced after this season yet the same drive and determination in the face of still high odds of death would remain and would continue to drive these men to push the boundaries of speed and technology. No other film since has given such a broad but also realistically detailed and timely study of motor racing.

I’ve tried to keep spoilers to a minimum as I’m sure that there are many reading this who haven’t seen the film. I urge you to seek it out and, when watching it, remind yourselves that nothing like this had ever been seen on screen before. Slightly jarring moments of melodrama aside, Grand Prix is as perfect and thrilling a representation of the sport that you’ll find and, for me, remains the absolute definitive depiction of the sport of motor racing ever committed to film.

Film ‘89 Verdict – 9/10