Pan’s Labyrinth (2006).

The beauty of the movies is, for me, the ability for the fantasy to bleed into the real. I don’t mean that film should be limited to the fantastical but that it allows worlds, people, lives and situations which are alien to me to become real, if only for the duration of that film. This is the secret of good movies and, for the great ones, this bleeding does not stop as the end titles go up. It continues, the grip it has can last for hours, days, months or, for those touched with true greatness, for a lifetime.

It occurred to me a while ago how many films which mean so much to me are often about this process, about how the fantasy meets and influences the real. Films like Field of Dreams, Cinema Paradiso or Martin Scorsese’s Hugo. They are films which explore the seams between dimensions, commenting on and celebrating them in a way which I always find incredibly moving.

Of course, the fantasy is not always a happy one; sometimes it lives in the darkness, in the shadows and in the black crevasses of our minds and if there is one film maker who can reveal this darkness, who can celebrate its unflinching bleakness in a way which is as moving and captivating as any of those aforementioned films, it’s Guillermo del Toro.

Del Toro has made some truly wonderful films – from the action-packed fun of Hellboy, Hellboy II: The Golden Army and Pacific Rim, to the stylised gothic creepiness of Crimson Peak, and the romanticism of his Oscar winning The Shape Of Water – but I, like so many, have always believed that his most perfect achievements were two of his Spanish language films, Pan’s Labyrinth and The Devil’s Backbone.

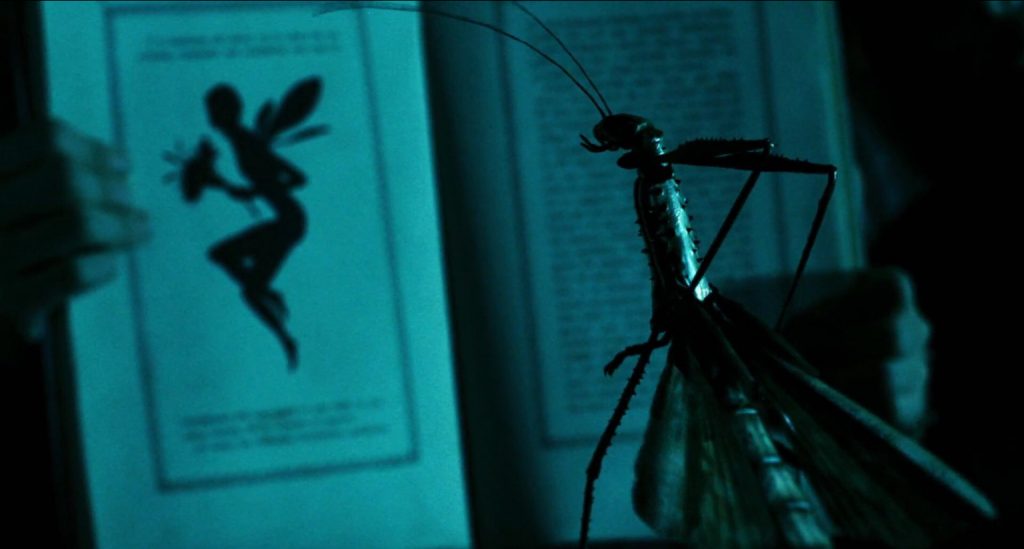

The most celebrated of these two films is undoubtedly Pan’s Labyrinth (El Laberinto del Fauno). Released in 2006, it tells the story of Ofelia (Ivana Baquero), a 10-year-old girl who moves with her mother, Carmen (Ariadna Gil), into the countryside to join her new stepfather Captain Vidal (Sergi López). Vidal is a Falangist charged with hunting down the remnants of the anti-Franco guerrillas hiding in the nearby forest. On the journey, Ofelia finds a strange looking insect which seems to follow her around. Later, as she lies in bed, the insect enters her bedroom and magically transforms into a fairy. The Fairy then directs the girl to an abandoned Labyrinth, a short walk from the mill in which they are now living.

It’s in this Labyrinth that she meets the Faun, a mythical creature that tells her she is the reincarnation of Princess Moanna, daughter to the King of The Underworld. But in order to prove that she still has some of the magic in her, she has to pass three tasks. Once these are completed she will be able to take her rightful place in her Kingdom and to live forever as it’s Princess.

The three tasks involve taking a key from the inside a giant and quite hideous toad, retrieving a dagger from the mysterious Pale Man, and drawing blood from an innocent. At the same time she must contend with her increasingly violent and oppressive stepfather, and her mother who is pregnant and suffering terribly from it.

This is a violent and dangerous world. Although the Spanish Civil War has ended about five years ago there is still fighting in the forest. There are constant tensions between the soldiers led by Captain Vidal and the locals, many of whom are sympathetic to the rebels. It’s a clash between the real and the fantastical.

Del Toro has said many times that Pan’s Labyrinth is his most personal film, and it’s obviously one he feels a lot of pride for. He’s spoken about how much work went into its development, how there are more layers to it than just about any other film he’s made. It‘s a film in which he explores many of his main concerns and preoccupations and accomplishes it most successfully.

The power of del Toro is that he understands the meaning and the importance of monsters. For him they are not mere objects to create fear, but are conduits in which we understand our own fears. The monster is a visual representation of those aspects of life that we have difficulty understanding – violence, death, creation, fear, amongst other things. These are not always tangible nor easily described in neat sentences. Take for example Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, which has been the subject of many books exploring the power and the meaning of the most famous of monsters. It has been remade on film and for television countless times, and each reincarnation differs in what it has to say and what the monster represents.

The monsters in Pan’s Labyrinth are, for Ofelia, a means of escape from the true horror that she lives in. In the world of Fairy Tales there are rules which are easily understandable to a ten-year-old in a way that adult life is not.

How can Ofelia’s mother be attracted to this awful man? The Captain is supposedly fighting bad guys and yet the rebels treat her well when he does not. Why did her real father die and why is her mother so ill right now? These are issues too big for a child to understand, but a mythical creature from a book can give her an easily understandable and straightforward quest – complete task A, then B, then C – and the reward is desirable and achievable. The complexity of the real world is not so easily defined, there is no beginning, middle or end, it is constant, and this can be uncomfortable compared to the structure of a story.

Ofelia says very little; she complains a bit but that’s because she’s a young girl but we see her thoughts writ large on her face. Del Toro has said that the most important image on screen is the glance, and it is through the glances of the characters, with their personalities displayed in every furrow of the brow, that we understand what they are feeling and experiencing. From the moment we first see Mercedes (Maribel Verdú), we know of her sympathy for the rebels. We see that she is a caring woman, constantly living in fear, but courageous in the face of evil. In Ofelia’s mother we see the pain of pregnancy and the desperate need for love and companionship that has been missing since the death of her first husband. Because she is so fearful of being alone she is willing to overlook the violence and lack of love from her new husband.

Captain Vidal is perhaps the most interesting character. He could easily have been one-dimensional – a monster with no nuance – yet, as the film progresses, we are given tantalising glimpses into his subconscious. His anger and his need for order (if it wasn’t fascism it would have certainly been something else) came from his father, a man who is revered in the Franco army and of whom countless stories exist. Yet for Vidal his father is a constant reminder of his own failures. He knows he is a little man who can’t live up to his father’s reputation. He’s full of self-loathing and hatred so he dominates through fear and violence. There are moments when he seems to display acute insight, yet, for the majority of the film, he fails to notice that some of those closest to him – Mercedes or the Doctor for example – are conspiring against him. He’s also the source of ridicule from some of his own domestic staff and if he found out he’d probably profess an air of disinterest whilst condemning them to death for undermining him. In one moment whilst shaving, he even slices a straight razor across his reflected neck, an indication of his self-loathing and fragility. Despite the grotesques that Ofelia meets, the true monster of the film is undoubtedly Captain Vidal.

The monsters are some of the most beautifully realised creations ever seen on film, starting with the faun. The title is a little misleading as the character Pan never plays a part or is mentioned. The original Spanish title – El Laberinto del Fauno – translates to The Labyrinth of the Faun, and it’s the faun that plays the most dominant role of the monsters. Played elegantly by Doug Jones who has worked with del Toro on a number of projects Mimic (1997), Hellboy (2004), Hellboy II: The Golden Army (2008), Crimson Peak (2015), and The Shape of Water (2017)), although he’s always covered in make-up. Jones is a remarkably physical actor who brings to life both the faun and the terrifying Pale Man. He’s unsympathetic and untrustworthy, but we are unable to take our eyes off him.

The Pale Man is probably the most famous of the creatures in Pan’s Labyrinth, and possibly del Toro’s entire body of work. With its eyes hidden in the palms of its hands and its jerking, uncoordinated movement, the Pale Man is a wonderfully realised creation.

The entire film is a visual delight, with the cinematographer (Guillermo Navarro), Art Direction (Eugenio Caballer) & Set Decoration (Pilar Revuelta), and Make-up (David Martí and Montse Ribé) all winning Academy Awards for their work. Pan’s Labyrinth was nominated for 6 Oscars including Best Foreign Language Film (which it lost to the brilliant The Lives of Others), Best Original Screenplay (del Toro) and Best Score. Javier Navarrete’s music conjures a wonderful blend of intrigue and lightness, especially the main theme, fittingly named Mercedes Lullaby.

Pan’s Labyrinth is one of those rare films which bridges fantasy and reality, realising the intrinsic links between horror and fairy tales. This is something we have forgotten in this Disneyfied world. It shows us the importance of fantasy, not just as an escape from the real world, but also in how it helps us cope with the real world. It’s a wonderful film, a masterpiece which effortlessly sways from horror to lullaby, between wars and dreams, cemented together with everyday heroism. Del Toro is one of the finest directors we have, and this is, for me, his opus, a masterwork which has haunted me since the first time I experienced it, one that captures the majesty of what film can achieve; it is cinema at its greatest.

Film ‘89 Verdict – 10/10