Quentin Tarantino’s first 25 years, Part 8 – Django Unchained (2012).

“The D is silent.”

In 2012, having hopped from one genre to the other for the preceding decade with his tales of criminality, homages to martial arts films and Grind-house cinema, auteur director Quentin Tarantino took his first foray into that most beloved genre, one teeming with classics across almost a century of cinema, the Western. Taking inspiration from and paying homage to the Spaghetti Western, this latest outing would be a loose remake and quasi-sequel of sorts to the Django series of Spaghetti Westerns. The star of the original 1966 film Django, Franco Nero, would also appear in a small role. The whimsical exchange between Franco Nero’s character and the new iteration of Django where Nero asks him to spell his name only to be told that the “D” is silent, his response of “I know” should please fans of the original film immensely.

The nods and winks to innumerable Westerns of yesteryear would proliferate the film, be they musical cues and actual songs lifted wholesale or general nods to the style with the use of crash-zooms and whip-pans. The purposeful use of stylistic flourishes to mimic the films Tarantino holds dear to him is part of his trademark style as is his penchant for tonal shifts between serious subject matter like racial justice (and injustice) and some gleefully absurd humour (the KKK’s meeting where they discuss their hoods) that is one of his many calling cards.

Will Smith originally turned down the lead role that would later go to Jamie Foxx. Foxx plays a slave who having been separated from his wife, is rescued by German bounty hunter, Dr. King Schultz as Django can identify three brothers who Schultz is looking for. Waltz won a Best Supporting Actor Academy Award in a role for which the description ‘Supporting’ seems rather insufficient. As much as Foxx is great as Django, to call Waltz’s role a mere supporting character is paying him short shrift. This is a film with two equal leads, one black, the other white and between them is formed a friendship and working partnership that flies in the face of the extreme racial injustice that is seen pretty much everywhere else in the film.

Tarantino’s film bears striking similarities to Skin Game a little seen 1971 Western with overt comedic overtones starring James Garner and Louis Gossett Jnr. as friends, one white, the other black, who scam slavers. Peppering a film that features such serious subject matter, that of slavery, with moments of overt, at times cartoonish humour is something that Tarantino is wholly adept at. The striking of that fine balance in tone whilst in no way shying away from the horrific treatment of African American slaves at the hands of their white masters is no easy feat. And makes no bones about it, there are moments throughout Django Unchained which are sickening, be it the flogging of women, forced Mandingo fighting or the way that black people are generally mistreated throughout.

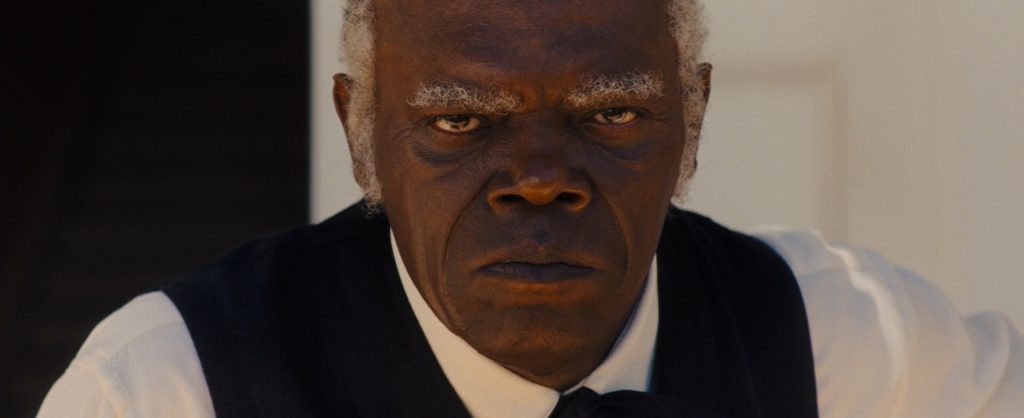

Tarantino has courted controversy in the past and earned the consternation of the likes of fellow director Spike Lee for his character’s flagrant and often far too comfortable use of a certain racial slur beginning with ‘n’ and that same word is used more here than all his other films put together. But what this film does is portray its many racist characters, including most disturbingly, Samuel L. Jackson’s hateful Stephen, as the reprehensible characters they truly are and amongst the many hats Django Unchained wears is that of an out and out revenge film. The initial plot thread of Django aiding Schultz in his quest to track and kill the Brittle Brothers is brought to a fairly swift conclusion after which Schultz, a man very adept at killing, trains Django in the art of death dealing with a six-shooter. As well as the accompanying training montage we are also shown some simply jaw dropping vistas throughout Django and Schultz’s travels courtesy of director of photography, Robert Richardson. Richardson has become Tarantino’s go-to DoP of choice and for good reason. Much as he did in the Kill Bill films, Inglourious Basterds and later on in The Hateful Eight, Richardson makes the most of the stunningly expansive Wyoming, Louisiana and California locales. Django is as much a feast for the eyes as any of Richardson’s other Tarantino films.

Circling back to it’s revenge themes, Django introduces several would-be antagonists before we are eventually introduced to the true villain of the piece, one Calvin Candie played by none other than Leonardo DiCaprio. Having never played an out and out villain, DiCaprio fully indulges his darker side but Candie always tries to mask his base brutality behind a veil of fey gentlemanly charm. Following our introduction to Candie we are shown the brutality of a Mandingo fight with Candie watching and cheering his sickening, joyous approval. Along with his house servant Stephen, the pair form the villainous core of a film already brimming with despicable individuals. Candie is now the master of Django’s wife Broomhilda, played by the wonderful Kerry Washington, and his engagement in a cat and mouse game with Schultz and Django as they try to free her gives the director one of many opportunities to indulge in arguably his most well known trademark, that unmistakable Tarantino dialogue. The focus of the majority of the most memorable dialogue scenes is Waltz who commands the screen with a performance that doesn’t get the same level of acclaim as his turn as Hans Landa in Inglourious Basterds but is arguably equal to it due in no small part to how likeable his character is.

As much as it has numerous moments of explosive violence, Django Unchained has many extended dialogue scenes throughout its 2 hour 45 minute runtime. The film snagged its second Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay for Quentin Tarantino and the dialogue is at times up to the director’s usual standards. That said, this is the first Tarantino film made after the tragic death of his long time collaborative partner Sally Menke and this is the first Tarantino film where the considerable length is felt to the film’s detriment. In the last third of the film there are certainly entire scenes that could do with a trim or could be lifted out entirely without harming the narrative. Menke had an innate understanding of the natural flow of a film and the effectiveness of her judicious editing simply cannot be understated. Without her, Tarantino’s self indulgence wins over in a few scenes where the absurd humour is allowed to overpower the story progression. The scene where Django once more finds himself in chains with Tarantino making an ill-advised cameo, feels completely unnecessary and is one of several scenes that drag the film when it should be building and gaining momentum towards its admittedly gloriously bloody finale.

Other moments of overindulgence that pulled me out of the film were Tarantino’s use of some contemporary music cues and songs and the reuse of music from Spaghetti Westerns that I’m at least vaguely familiar with. It’s some of the more out of place humour that serves to remind you that you’re very much watching a Tarantino film and this does harm the film insomuch that it would be refreshing to a least once have a film that bucked Tarantino’s own trends as he so subversively bucked trends and eschewed convention in his earlier films. Personally I don’t need the on the nose humour with such frequency as it’s used here nor the plethora of referential nods to other films.

As much as Django Unchained is a damn fine film in many respects, it is somewhat bloated and I long for more restrained and mature films as the director gets older. If fifteen minutes or so were trimmed from its runtime then I’m sure this would be ranked in the top tier of both Tarantino’s work and also amongst the very best modern day Westerns. As it stands it’s certainly better than Death Proof and is for me the better of Tarantino’s two Westerns. There’s a heck of a lot to like in Django Unchained. It has several interweaving subplots and the writing helps layer the characters. The performances are uniformly great, it’s beautifully lensed and when it does unleash the carnage it certainly doesn’t hold back. It’s rich and has that unmistakable Tarantino edge and doesn’t ever compromise on its director’s vision even though the absence of Sally Menke, one of the very best editors in the business and Tarantino’s most cherished colleague is felt by way of its slightly lengthy runtime. That said, Django Unchained is bold, brutal and, on the whole, entertaining filmmaking from one of this generations most important and influential directors.

Film ‘89 Verdict – 8/10