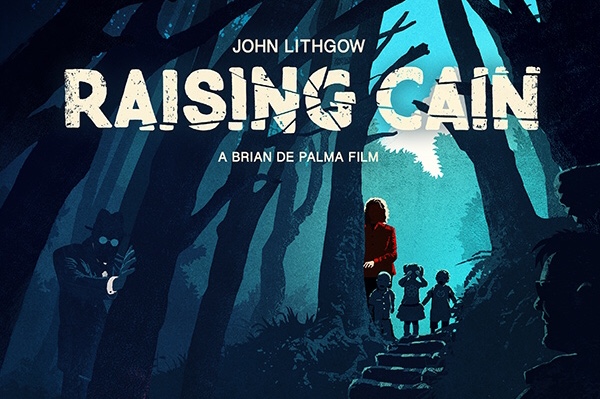

Raising Cain (1992) / Raising Cain: Recut (2012) – Review.

When discussing the filmography of Brian De Palma there are a number of obvious films that come to mind – Scarface, The Untouchables, Carlito’s Way, Obsession and Dressed To Kill being just a few. One film which is rarely mentioned however, is one of his best – 1992’s Raising Cain.

One issue that arises when discussing Raising Cain is how to describe the film without giving too much away. When I first saw it back when it was initially released, I went in without knowing anything about it. It was Brian De Palma after all, what more would I need to know? Yes it was his first film after the debacle that was The Bonfire of the Vanities but even that was interesting from a cinematic point of view (if not a comedic one as intended).

Why Raising Cain would appeal to De Palma after the difficulties he faced making The Bonfire of the Vanities is obvious. Written by himself and with a much smaller budget, it marked a return to the style of film that had made him famous in the ‘70s. It was a film that was more controllable and, what’s more, the control would be in his hands. It undoubtedly made him feel most comfortable – it was about sex, death, personality disorders and would utilise a number of stylistic flourishes that he had already mastered. It was a return to the Hitchcockian filmmaking that he had long been associated with.

In the end the film was only a modest success, grossing a little over $36million worldwide, on a budget of $12 million, and was only marginally successful with the critics. It proved one of the most divisive films of the year and remains so when focusing on De Palma’s fairly wild career. Some see it as a brilliant example of De Palma being De Palma, others see it as the director becoming almost a parody of himself. De Palma has admitted that he struggled with it in the editing room. Initially he wanted it to be fairly nonlinear, to focus first on one character before the switching its main focus later on. This however, proved disastrous in test screenings with audiences confused about exactly what was happening and when. In the end De Palma caved in and presented a compromised version – one that was more linear in its approach.

Written with its star, John Lithgow, in mind, Raising Cain revolves around a child psychologist, Dr Carter Nix. In the very first scene of the theatrical version he tries to convince a friend, whom he knows from playdates with their kids in the local park, to allow her daughter to take part in an experiment conducted by his father. His own daughter, he says, is taking part and he needs more subjects. The mother declines this offer and is quite shocked that he would do this to his own child. The conversation becomes strained and then, out of the blue, Nix attacks the woman using chloroform to subdue her. It’s at this point where panic sets in and Cain shows up (also played by John Lithgow). Cain is everything that Carter is not – confident, ruthless and cool under pressure.

Cain and Carter are the same person. As, we will later find out, are Margot and Josh. Dr Nix is suffering from Multiple Personality Disorder and is being forced by the Cain personality, along with that of his long dead father, to kidnap children so that experiments that had once been conducted on him can continue. This is not a spoiler – one of the copy lines of the film was ‘When Jenny Cheated On Her Husband, He Didn’t Just Leave, He Split!’ Another copy line ‘De-ranged, De-mented, De-ceptive, De Palma’ is just perfect.

If you are looking for logic then this cut of Raising Cain will not be for you. It leaves logic at the front door, slamming that door in its face. It’s not a film concerned with tying up loose ends. In fact it seems to embrace them, focusing instead on style, mood and paranoia.

Carter’s wife Jenny, a Cancer Specialist in the local hospital (played by the wonderful Lolita Davidovich) becomes suspicious of her husband and doesn’t like the attention he’s giving their daughter. Not that she’s completely innocent herself, she’s having an affair with the husband of one of her dying patients. This provides a subplot regarding a gift that she had bought for both men which, although seemingly trivial, is really well thought out and offers moments of real tension. It also gives us one of two genuine shocks in the film which are worthy of any great thriller.

Tension is one thing that you would expect from De Palma and he cranks it up on numerous occasions. Using his trademark slow-motion camera, with an emphasis on Dutch angles and wide-angle lenses, you are kept on the edge of your seat throughout, even when it doesn’t seem to make a lot of sense.

There is one very long take using a steady cam which follows a pair of detectives and Dr. Waldheim (played by the wonderful Frances Sternhagen), a former co-worker of the late Dr Nix Senior, as they walk the labyrinthine corridors and escalators of the Police precinct, which is pure De Palma Gold. It is essentially one long scene full of exposition but the way it’s filmed takes our mind off the length and the fact that it’s nothing more than basic information filler, and ensures that it is interesting and amusing.

This is just one example of a bravura filmmaker knowing exactly what he needs to do to make the mundane interesting. Another example of this is the ending. Amy, the daughter of Carter and Jenny, has been kidnapped. Carter has been found out and is being interrogated by the police. We learn the truth of Carter’s past for the first time and John Lithgow gets to have fun playing multiple characters in the same scene. Even a very odd moment earlier involving a young child with a strange voice is explained and suddenly makes perfect sense. It is here that De Palma’s use of slo-mo, the wonderful soundtrack by Pino Donaggio, the cinematography by Stephen H. Burum and the suspension of disbelief that we have accepted throughout really comes up trumps.

If you have bought into the film to this point the ending will work beautifully. If you have found the whole thing ludicrous and baffling, the ending might just push you over the edge. Raising Cain’s ending is exactly the same in both cuts of the film. The beginning, however, is quite different.

If you have bought into the film to this point the ending will work beautifully. If you have found the whole thing ludicrous and baffling, the ending might just push you over the edge. Raising Cain’s ending is exactly the same in both cuts of the film. The beginning, however, is quite different.

In 2012 a new cut of the film emerged, a fan edit by film and TV director Peet Gelderblom, which was originally released on Indiewire. Gelderblom was watching Raising Cain one evening with his girlfriend. Whilst he loved the film, his girlfriend didn’t and, having explained her reasoning, Gelderblom had to admit that he understood her reservations. He began to look into the film in more detail and discovered a quote by De Palma on CHUD.com in which he said he had had trouble putting together the first half of the film. Gelderblom also found a copy of the second draft of the film, then entitled Father’s Day, which had been circulating online. Although there were many different scenes in this draft which were changed in subsequent versions – for example, the beginning takes place in a bookshop rather than the clock shop that was eventually used) – it did reveal a structure to the opening scenes which was very different to the released film. On discovering this Gelderblom decided to try and rearrange the film so that it would be more in line with this early draft.

The end result was Raising Cain Recut. There are no extra scenes in the Recut version. Gelderblom didn’t have access to any material from the cutting room floor, just the footage that was in the theatrical cut (he basically put his DVD in his computer, ripped it and reedited it from there) but he still managed to rearrange the first half of the film so that not only did it fit with De Palma’s original ideas, but it also increased the tension, put off the revelation of Carter’s multiple personalities until almost a third of the way through, and created a moment of genuine shock that had been somewhat ineffective and even telegraphed in the original cut.

Raising Cain Recut (known as the Director’s Cut on the Arrow Limited Edition Blu-ray that was released a last year), begins by focusing entirely on Jenny. The opening scene I described earlier doesn’t appear until over twenty minutes in and we don’t see Cain for almost thirty minutes. This is the biggest change but it is significant. Mostly however, the recut, whilst continuing to force the viewer to pay attention, also rewards the viewer with more effective pay-offs. De Palma was informed on this new cut and after watching it himself claimed that it managed to achieve “what we didn’t accomplish on the initial release on the film. It’s what I originally wanted the film to be.” He went on to insist that it be included on the upcoming Blu-Ray releases.

It must be said that the Recut is the more satisfying edit of the film. My admiration for the film undoubtedly came from watching the original version, but on seeing this new version, I now believe it to be the superior cut. The question remains though, would I have liked the theatrical version as much if I had watched the new cut first? I must admit that I would have probably found it disappointing. My advice if you have not seen Raising Cain before, is to skip the Theatrical version and go straight to the Recut/Director’s cut instead.

Either way, Raising Cain remains a smorgasbord of narrative styles, including flashbacks, voiceover, dream sequences and plenty of McGuffins along with continuous shifts in perspective.

It’s often said that De Palma frequently rips off Hitchcock. It’s an accusation that has been used against him more often than can be counted. At the same time it’s an accusation that has also been embraced by his many fans. I have never believed that he rips off the Master of Suspense although I have to acknowledge the influence that Hitchcock has had on him is significant. To sling this at him as an insult is to undermine the skill that De Palma has as a filmmaker. What’s wrong with standing on the shoulders of giants as long as you make your work distinctly your own? And De Palma certainly does just that. It could be argued that Raising Cain’s biggest influence was Hitchcock’s Psycho, something that is much more obvious in the Recut version. This would place it nicely in a trilogy of films which would include Sisters and Body Double.

Other obvious influences on Raising Cain are Michael Powell’s 1960 classic, Peeping Tom, and the films of Dario Argento. Intriguingly, John Lithgow also proposes that another major influence was no less than Ingmar Bergman. Whilst this didn’t immediately come to mind when I first saw Raising Cain, as soon as I heard Lithgow’s assertion, I thought of Bergman’s Wild Strawberries with its use of voice-overs and flashbacks and the importance clocks have throughout.

Other obvious influences on Raising Cain are Michael Powell’s 1960 classic, Peeping Tom, and the films of Dario Argento. Intriguingly, John Lithgow also proposes that another major influence was no less than Ingmar Bergman. Whilst this didn’t immediately come to mind when I first saw Raising Cain, as soon as I heard Lithgow’s assertion, I thought of Bergman’s Wild Strawberries with its use of voice-overs and flashbacks and the importance clocks have throughout.

Raising Cain is a delirious dream of a film. From the music to the editing to the off-kilter camera techniques, to the very black humour that permeates throughout, it is a wild ride. I can understand it if some don’t buy into it as it’s not a film that you can sit back and passively enjoy. You have to accept what it is from the very start and continue accepting it until the very last shot (which is itself a joyous example of De Palma’s wonderfully macabre sense of humour).

If you choose to accept this continuous sense of delirium then you are in for a real treat. I think it’s now fairly obvious that I did very much enjoy Raising Cain and as I was watching it, a description popped to mind that persisted and I think sums up the movie perfectly – Raising Cain is a cinephile’s wet dream. I think De Palma would be happy with that.

Film ‘89 Verdict:

Recut/Director’s Cut – 9/10

Theatrical Cut – 8/10