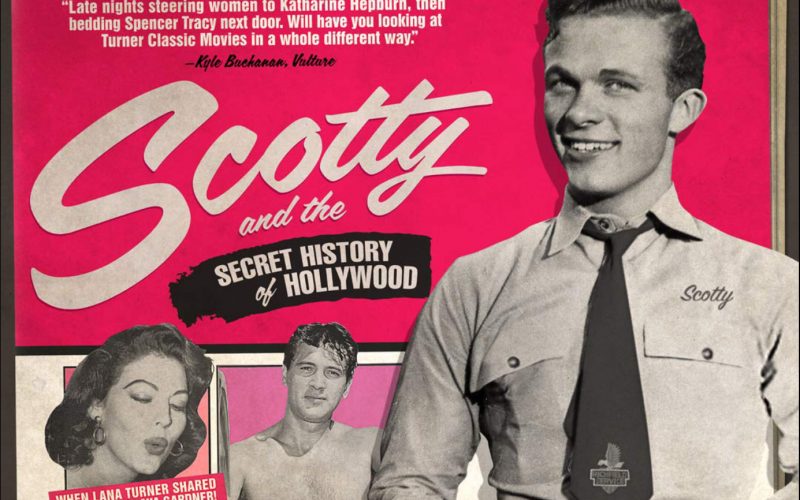

Scotty and the Secret History of Hollywood (2018).

The Golden Age of Hollywood was lined with shame and secrets, and people have been spilling the tea continually since then. (Kenneth Anger’s seminal Hollywood Babylon is nearing its sixtieth anniversary, in fact.) It’s common knowledge that many directors and actors lived double lives in the spotlight, to better adhere to post-Hays Code morality clauses laid down by the studio mandarins. But for as many Rock Hudsons as we knew about, there are still more people who went to their grave in the closet.

Enter Scotty Bowers, a curly-haired leprechaun of a man in his 90s. Bowers published his own book about the subject in 2012 called Full Service, a tell-all about his time spent running an illicit sex service out of a Hollywood Boulevard gas station from 1945 through the 1980s. He’s careful not to call himself a pimp, because money never changed hands from the young studs in his stable to Scotty himself – he merely made love connections between, say, Walter Pidgeon and some corn-fed, midwestern young man.

Documentarian Matt Tyrnauer (Valentino: The Last Emperor) took an immediate liking to the book and the man, and set upon Los Angeles to shoot 300 hours of Bowers and his wife as they went about life in the hills above the city sprawl. The resulting film is bifurcated between following Scotty Bowers listening to him recount his exploits between the sheets with a who’s-who of platinum luminaries, and trying to parse the psychology behind what makes the guy tick. The same man who “entertained” Spencer Tracy and Cary Grant, it turns out, was molested by Catholic priests as a child and even hired himself out to a long list of Chicago clergy in the 1920s when he realized he could make money from his body.

It’s easy to assume that most viewers will show up expecting a full and sordid account of which box office idols preferred which sex acts, and there is that. But Tyrnauer is more interested in trekking through the two trash-filled houses which Bowers has filled with a lifetime of detritus, watching the nonagenarian deliberate whether or not to claim an abandoned toilet on the side of Mulholland Drive because “it still works.” There’s a psychological connection the director is drawing between Bowers’ hardscrabble early 20th century childhood, the mind-bending bomb-blast of fighting in the Pacific theater in World War II, the decision to enter sex work in the 1940s, and the impending toll of the AIDS scourge of the 1980s, when he quit running his book. Add to that a late-reel reveal of a daughter who died in her 20s of a botched abortion and you get a sadder picture of the aged bon vivant you met at the beginning of the movie.

As an aside, hoarding is generally thought to be a psychological dysfunction brought on by a traumatic event, and it would appear that Scotty Bowers has his pick of them to choose from.

These are all fascinating elements, more than worthy of a documentary, but there is one element of Tyrnauer’s treatment of Bowers’s story which seems foggy; the insinuation that the man was some sort of champion for gay men and women because he facilitated hookups in back rooms. Such talking heads as Stephen Fry use exultant language to describe Bowers’ accomplishments, to give him the credit of entering a civil rights fray decades before it became de rigeur. My impression is that Bowers was doing what felt good – following his own hedonism – and any social benefit was merely secondary to his carnality.

Tyrnauer uses the tide of renown from Bowers’s book Full Service as a framing device, tracking back and forth from salons and parlors to bookstores and parties as people celebrate the release and revelations from the volume. Gay men queue up to thank the author for shining a spotlight on a repressive moral age in America, where homosexuality was verboten and it was mandatory to conceal your sexual bent if it didn’t conform to the midcentury Wasp ideal. In that respect the need for a man like Bowers and a movie like this one makes itself evident. One thing we know for sure is that there’s a ton of buried history in the U.S.A., and the work of disinterring the skeletons of previous epochs is ongoing. There is an acknowledgment by the director of the involuntary nature of Bowers’ story, how maybe Spencer Tracy wouldn’t have wanted the truth exposed, but Bowers waves that away by citing the amount of time his subjects have been dead, as if time in the dirt neutralizes those charges against him.

When Tyrnauer is wrapping up his travelogue through Bowers’ life, he does present his subject with a pointed question, the only one the director opted to include in his final edit; Do you think that being molested as a child demented you in any way, perhaps dictating the adult life the viewer just witnessed? The movie presents numerous head-spinning revelations, but Bowers dismisses all the presumed trauma of his brutal upbringing by insisting he was making defined choices every step of the way. In spite of his informality and loose-lipped style, the subject is very much a man of his generation, unwilling to admit flaw or vulnerability. He’s unchallenged for the most part, which leaves some questions unanswered.

It goes without saying that this film is in limited release in America right now, so seeing it might be a task in itself, but it’s worth the hunt. You’ll never look at pictures of Cary Grant and Randolph Scott the same way again. You have been warned.

Film ‘89 Verdict – 7/10

Scotty and the Secret History of Hollywood is currently on a limited US theatrical release.