The History of ‘50s Science-Fiction Cinema – Part 1.

Alien Invasions, monsters, mad scientists, dashing heroes and women who were sometimes intelligent, mostly beautiful and always capable of belting out one hell of a scream. There’s something about classic science-fiction that still resonates today. Yet for many reasons, they’ve never really been taken as seriously as films from other genres and periods.

Film history is the history of waves. Moments in time in which a group of filmmakers from particular countries, inspired to follow a style of filmmaking that, for whatever reason, flourishes for a number of years before losing prominence. The German Expressionist movement and the Russian School of Montage of the 1920s, the Italian Neo-realists of the late ‘40s and early ‘50s, the British New Wave of the ‘60s, the French Novelle Vague in the early ‘60s are just a few examples.

But few movements have been as popular with the general public than the wave of science fiction films of the 1950s. They have been dismissed because many of them lacked quality and also one suspects, because they were so popular with youngsters that it’s easy to dismiss them as mere entertainment rather than art. Yet the genre films of this period undoubtedly fit the definition of a ‘wave’. Firstly, they were mostly confined to a specific location and era; secondly, they reflected the mood and anxieties of that specific era; and finally, because they had a distinct influence on filmmakers from later periods all around the world.

As is often the case, there are a number of reasons for this particular wave both culturally and technologically. World War II had ended and was replaced by a new Cold War that would at times, prove just as terrifying even though it lacked the immediacy of the battlefield like in previous wars. It was also a time of massive technological optimism, which ran alongside, and sometimes counter to, the unease and fear of the cold war.

The relief at the end of the last World War was still being felt and celebrated, and horizons were getting bigger whilst the world was getting smaller. Significantly, it was also a time when people began looking beyond the boundaries of the Earth and into space. All these elements came together at a time when it became possible to make films more cheaply while still finding an audience. The films reflected all these hopes, anxieties, boundaries and the beliefs that the world and the universe at large was feeling at that particular moment. There are too many films to list every one just as there are many that are not worth discussing, but there are a number of classics which are essential to anyone who wishes to dig into this treasure trove.

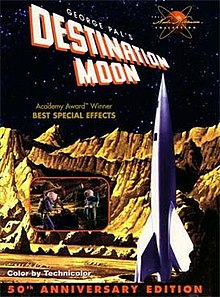

The decade didn’t start with many great movies but June 27th 1950 saw the release of Destination Moon, a film which legendary science-fiction author Isaac Asimov described as ‘the first intelligent science-fiction movie made’. It’s a prophetic film which reflected the optimistic and forward thinking idealism that was gripping the United States at the time. It was perhaps the first film to take space exploration and its dangers seriously. It follows the voyage of four astronauts on their way to the moon and focuses on the scientific and technological hurdles that needed to be overcome. The crew land on the moon but use up too much fuel for them all to return. Mission control informs them that in order for their Luna landing craft to be light enough to take off and return home, one astronaut needs to remain. The drama does not come from an external and unknown source, it stems from the very real tension that comes from an extreme situation and how the crew handles it. In many ways it’s a precursor to Ron Howard’s Apollo 13. Watching it today it’s surprising how scientifically accurate the film is, especially as it was made almost twenty years before man eventually landed on the moon. Destination Moon was directed by Irving Pichel and produced by George Pal, a name we will hear again later.

The decade didn’t start with many great movies but June 27th 1950 saw the release of Destination Moon, a film which legendary science-fiction author Isaac Asimov described as ‘the first intelligent science-fiction movie made’. It’s a prophetic film which reflected the optimistic and forward thinking idealism that was gripping the United States at the time. It was perhaps the first film to take space exploration and its dangers seriously. It follows the voyage of four astronauts on their way to the moon and focuses on the scientific and technological hurdles that needed to be overcome. The crew land on the moon but use up too much fuel for them all to return. Mission control informs them that in order for their Luna landing craft to be light enough to take off and return home, one astronaut needs to remain. The drama does not come from an external and unknown source, it stems from the very real tension that comes from an extreme situation and how the crew handles it. In many ways it’s a precursor to Ron Howard’s Apollo 13. Watching it today it’s surprising how scientifically accurate the film is, especially as it was made almost twenty years before man eventually landed on the moon. Destination Moon was directed by Irving Pichel and produced by George Pal, a name we will hear again later.

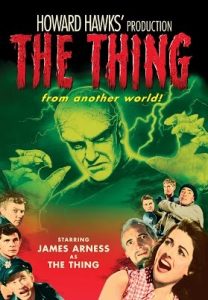

1951 was one of the greatest years of this period with three masterpieces released. The first of these was The Thing From Another World, which was released on April 6th. Based on the John W. Campbell Jnr. novella Who Goes There, The Thing From Another World tells the story of an alien invasion at the North Pole. The scientists and military men of an expeditionary outpost discover an alien life form frozen in ice. The ice melts and the alien is released. The men (and one woman – Margaret Sheridan) are trapped and caught in a storm and have no choice but to confront the terror that they are facing. The heroes of the film are the military, men of action who just want to get out alive. The scientists are more problematic, especially the lead, Dr Carrington (played by Robert Cornthwaite who also starred in Mant, the film-within-a-film in Joe Dante’s loving 1993 pastiche of the era, Matinee) who assumes that the alien is far more intelligent than humans and therefore, not interested in violence. Suffice to say, he was wrong. Directed by Christian Nyby and produced by Howard Hawks, The Thing From Another World is top class entertainment. Using Hawks‘ trademark rapid fire dialogue and a great cast it’s one of the highlights of the period and, although later eclipsed by John Carpenter’s 1982 remake, The Thing, it is still essential viewing.

1951 was one of the greatest years of this period with three masterpieces released. The first of these was The Thing From Another World, which was released on April 6th. Based on the John W. Campbell Jnr. novella Who Goes There, The Thing From Another World tells the story of an alien invasion at the North Pole. The scientists and military men of an expeditionary outpost discover an alien life form frozen in ice. The ice melts and the alien is released. The men (and one woman – Margaret Sheridan) are trapped and caught in a storm and have no choice but to confront the terror that they are facing. The heroes of the film are the military, men of action who just want to get out alive. The scientists are more problematic, especially the lead, Dr Carrington (played by Robert Cornthwaite who also starred in Mant, the film-within-a-film in Joe Dante’s loving 1993 pastiche of the era, Matinee) who assumes that the alien is far more intelligent than humans and therefore, not interested in violence. Suffice to say, he was wrong. Directed by Christian Nyby and produced by Howard Hawks, The Thing From Another World is top class entertainment. Using Hawks‘ trademark rapid fire dialogue and a great cast it’s one of the highlights of the period and, although later eclipsed by John Carpenter’s 1982 remake, The Thing, it is still essential viewing.

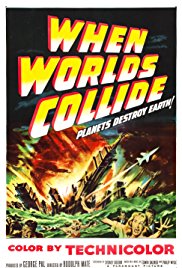

In August 1951 When Worlds Collide was released. The story is simple, a rogue star is discovered and in eight months time it’s going to crash into the earth destroying everything that we know. The heroes, Dr Joyce Hendron (Barbara Rush) and pilot David Randall (Richard Derr), try and organise giant arks to ferry a select number of people to a planet that is circling the star. When Worlds Collide reinforces the pattern that would be seen time and time again – the muscular, strong-jawed handsome hero accompanied by the strong-willed, beautiful and usually very intelligent female companion. Many saw it as a sequel of sorts to Destination Moon and, once again, it emphasises science over fantasy. It is also an allegory, a way of creatively expressing the fear of nuclear war without ever having to mention it directly.

In August 1951 When Worlds Collide was released. The story is simple, a rogue star is discovered and in eight months time it’s going to crash into the earth destroying everything that we know. The heroes, Dr Joyce Hendron (Barbara Rush) and pilot David Randall (Richard Derr), try and organise giant arks to ferry a select number of people to a planet that is circling the star. When Worlds Collide reinforces the pattern that would be seen time and time again – the muscular, strong-jawed handsome hero accompanied by the strong-willed, beautiful and usually very intelligent female companion. Many saw it as a sequel of sorts to Destination Moon and, once again, it emphasises science over fantasy. It is also an allegory, a way of creatively expressing the fear of nuclear war without ever having to mention it directly.

This fear of the destructive force that nuclear bombs could create is also explored in The Day The Earth Stood Still which was released in September 1951. The world is rocked one day with the appearance of a flying saucer which lands in Washington D.C. Two aliens appear – one a giant robot named Gort and the other a humanoid named Klaatu (brilliantly played by Michael Rennie). Klaatu is shot by an over anxious soldier and taken to hospital where he insists he needs to talk to the world’s leaders but, as any earthling could have told him, there are two major obstacles to talking openly with the world: paranoia and bureaucracy. Klaatu is told he can only speak to representatives of the US (they are afraid that Klaatu’s message may be against their national interests). In order to spread his message, Klaatu escapes and wanders the streets, mingling with the locals, and discovering that they are worth saving, even though they have what he sees as an irrational fear of his kind. His message is simple, the development of nuclear weapons is not only dangerous for the Earth but for others throughout the galaxy. It is admittedly, a none-too-subtle, anti-nuclear message, pleading with the leaders of the time to come together and put their petty differences aside. The Day The Earth Stood Still was directed by Robert Wise, who had started out as an editor working with Orson Welles on Citizen Kane and directing such diverse classics as The Haunting, The Sound Of Music, West Side Story and Star Trek: The Motion Picture. It‘s a wonderful film that transcends the genre and belongs in the haven of true science-fiction classics.

This fear of the destructive force that nuclear bombs could create is also explored in The Day The Earth Stood Still which was released in September 1951. The world is rocked one day with the appearance of a flying saucer which lands in Washington D.C. Two aliens appear – one a giant robot named Gort and the other a humanoid named Klaatu (brilliantly played by Michael Rennie). Klaatu is shot by an over anxious soldier and taken to hospital where he insists he needs to talk to the world’s leaders but, as any earthling could have told him, there are two major obstacles to talking openly with the world: paranoia and bureaucracy. Klaatu is told he can only speak to representatives of the US (they are afraid that Klaatu’s message may be against their national interests). In order to spread his message, Klaatu escapes and wanders the streets, mingling with the locals, and discovering that they are worth saving, even though they have what he sees as an irrational fear of his kind. His message is simple, the development of nuclear weapons is not only dangerous for the Earth but for others throughout the galaxy. It is admittedly, a none-too-subtle, anti-nuclear message, pleading with the leaders of the time to come together and put their petty differences aside. The Day The Earth Stood Still was directed by Robert Wise, who had started out as an editor working with Orson Welles on Citizen Kane and directing such diverse classics as The Haunting, The Sound Of Music, West Side Story and Star Trek: The Motion Picture. It‘s a wonderful film that transcends the genre and belongs in the haven of true science-fiction classics.

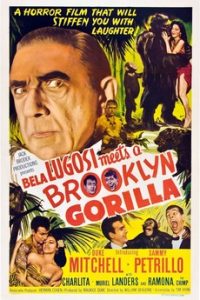

1952 wasn’t a stellar year for sci-fi although it did produce some marvelous titles including Captive Women, Untamed Women, Bela Lugosi Meets the Brooklyn Gorilla and, best of all, Zombies of the Stratosphere. Unfortunately, none of these films lived up to the promise of their wildly inventive titles. 1953 however, was a return to form with two classics and a number of other notable titles. First there was Invaders From Mars which was released April 22nd. This is perhaps the first great sci-fi to warn against the influence of communism. It was a time of heightened fear of Russia and its state ideology and could be seen almost every night on the TV news and commentary programmes. This was only 6 years after the House of Unamerican Activities blacklisted the original ‘Hollywood Ten’ – filmmakers who were accused of spreading pro-communist messages through their movies. Eventually, more than 300 artists were blacklisted and many of the biggest names in Hollywood, including Charlie Chaplin and Orson Welles were forced to go overseas to continue working.

1952 wasn’t a stellar year for sci-fi although it did produce some marvelous titles including Captive Women, Untamed Women, Bela Lugosi Meets the Brooklyn Gorilla and, best of all, Zombies of the Stratosphere. Unfortunately, none of these films lived up to the promise of their wildly inventive titles. 1953 however, was a return to form with two classics and a number of other notable titles. First there was Invaders From Mars which was released April 22nd. This is perhaps the first great sci-fi to warn against the influence of communism. It was a time of heightened fear of Russia and its state ideology and could be seen almost every night on the TV news and commentary programmes. This was only 6 years after the House of Unamerican Activities blacklisted the original ‘Hollywood Ten’ – filmmakers who were accused of spreading pro-communist messages through their movies. Eventually, more than 300 artists were blacklisted and many of the biggest names in Hollywood, including Charlie Chaplin and Orson Welles were forced to go overseas to continue working.

One of the strengths of sci-fi is its ability to pick up on the moods of the day and to either subtly reveal them or exploit them for narrative purposes. After the HUAC had attacked Hollywood, many producers and studio heads promised to make more anti-Soviet films, which was ironic given that the American Government had previously requested the studios portray Russia in a positive light in order to aid the immediate post-war effort. But studio bosses were, in many respects, politicians and they jumped at the opportunity to listen to the present administration, do their bidding and keep their jobs with minimum interference and additional red tape.

Films like 1949’s The Red Menace (Dir: R.G. Springsteen) & The Red Danube (Dir: George Sidney), Gulity Of Treason (1950 Dir: Felix E Feist) and the John Wayne starrer Big Jim McClain (1952, Dir: Edward Ludwig) had already covered the threat of Communism and there had also been a 1952 sci-fi, Red Planet Mars (see what they did there?) in which scientists received a message from our nearest solar cousin purporting that the planet was a utopia. The message then changes and, mirroring The Day The Earth Stood Still, the Martians threaten the earth with constant nuclear war because it has strayed from the teachings in the Bible. Revolutions break out around the world (including in the Soviet Union) and a new age of theocracy begins. The film has a lot of fine ideas but unfortunately the execution is left wanting.

The same cannot be said for Invaders From Mars. Directed by William Cameron Menzies (director of the 1936 sci-fi classic Things to Come and assistant director on Gone With The Wind – he directed the famous attack on Atlanta scenes) Invaders From Mars is told, in part, through the eyes of a child, something that is very common today but was less so in the ‘50s. One evening, little David Maclean is woken by a loud noise which he initially assumes is thunder. When he investigates however, he sees a flying saucer land in the nearby sand dunes. Pretty soon his family and other members of the community start acting strangely, lacking in emotion, except when punishing David for questioning them about what might be wrong. It is something that would be expanded upon a few years later in Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

After an act of sabotage on a rocket research plant, the army are called in and surround the saucer. The heroes, astronomer Dr. Stuart Kelston (Arthur Franz) accompanied by the very lovely Dr. Pat Blake (Helena Carter) and David are sucked into the sand dunes and discover a hidden network of caves which the Martians have created. They are captured by the Martians and we are introduced to their leader, a bodiless head which controls its minions telepathically. The Martians are using a devise which is attached to the back of a human’s neck to put them under the influence of the head. At the end of the film it looks like the whole thing may have been the result of an over active imagination and it seems that David has dreamt the whole thing, however, as he wakes from the dream, he hears a clap of thunder looks out the window and sees the same space ship descending from space.

Invaders from Mars is great entertainment even though it has a very dark undercurrent, and it has some wonderful visual effects with the Martian head deserving a special mention. It taps into anti-communist paranoia perfectly, especially in the first half. I’d highly recommend it especially if you’re a fan of Brad Bird’s brilliant The Iron Giant (1999) which was influenced by Invaders From Mars. It was remade in 1986 by Tobe Hooper.

In Part 2 we’ll continue our flight through the greatest sci-fi films of the 1950s, including such classics as The War Of The Worlds, The Creature from the Black Lagoon and the magnificent creature feature Them!