Woman in the Dunes (1964).

Every so often you come across a film that you had never previously heard of, but when you sit down to watch it, it impacts you so much that you just can’t believe you’d previously missed it. This can happen on social media or in the press (all too rarely as the mainstream media likes to concentrate more on promoting modern films), but more often than not, it occurs when listening to some of the great podcasts from around the world. It’s one of the reasons The Film ‘89 Podcast exists.

It was whilst listening to an old episode of Wrong Reel with Dave Eaves and James Hancock (WR230), that I first heard of the US Criterion Collection release of Woman in the Dunes. I’m not sure why it passed me by for so long as I’m a lover of Japanese Cinema, especially Ozu, Kurosawa, Mizoguchi and Naruse. They are films which capture the exotic nature of another culture, whilst also having a universality that is easy to empathise with. There’s an ordinariness about them that is easily translatable across borders and cultures, even directors that were once seen as distinctly Japanese, such as Yasujirô Ozu, speak to us personally.

Woman in the Dunes, directed by Hiroshi Teshigahara, is no different, even though its story, on face value at least, is an odd one. Niki Junpei (Eiji Okada – who was probably best known for playing Lui opposite the wonderful Emmanuelle Riva in Alain Resnais’s Hiroshima Mon Amour) is a teacher and ‘a bit of a scholar’ and he spends his days wandering around sand dunes searching for bugs. The day gets late and he is offered the chance to stay in the house of a local, which he happily accepts. The house is little more than a shack and is located at the bottom of a pit, surrounded on all sides by a very high wall of sand. The only way in or out is by climbing a rope ladder. When he gets to the bottom he meets his host, a widow (Kyōko Kishida -who also appeared in Ozu’s An Autumn Afternoon) who feeds him and helps him settle down. All is well.

The next morning he gets up early, eager to continue his bug hunt, and notices that the rope ladder is gone. He’s trapped. The woman doesn’t seem concerned and, although he doesn’t initially pick up on it, she seems to indicate that he is to remain. He is there, apparently, to help the woman dig the sand which is then lifted by buckets tied to ropes back to the surface by the locals. As the days pass, the man gets increasingly frustrated, rebelling against the trap he is in, until he is driven almost insane by thirst. In the end he capitulates and reluctantly begins to join the woman digging the sand.

We aren’t told much about the man or the woman. We know he is a teacher from Tokyo and he has three days leave, but beyond that there’s almost nothing. We never find out if he is married or if he has children or, beyond etymology, what his interests are. These are not important. As far as the woman is concerned, we never find out if she chose to live in this pit. We are told in passing that she had a husband and daughter, and that they are both buried in the sand somewhere. We also know that other men have been there before this current captive. She seems to accept her situation, and her ‘guest’s’ (her words not mine), as if it’s perfectly natural. In fact, she takes a certain pride in her job and her home.

She has the obvious desires – to talk to someone, to work alongside someone, and to touch and be touched by a man. She has passion within her that she has missed and, in one memorable scene, they have sex on the floor of the hut, her face distorted by the sand sticking to her face, the music almost discordant and antithetical to the scene we are watching. In fact, there are two elements that really stand out here. Firstly, the music by Tôru Takemitsu, which continually creates a conflict between what we see and what we hear. It keeps us on edge at all times, making us question what exactly we are seeing and what we should be feeling.

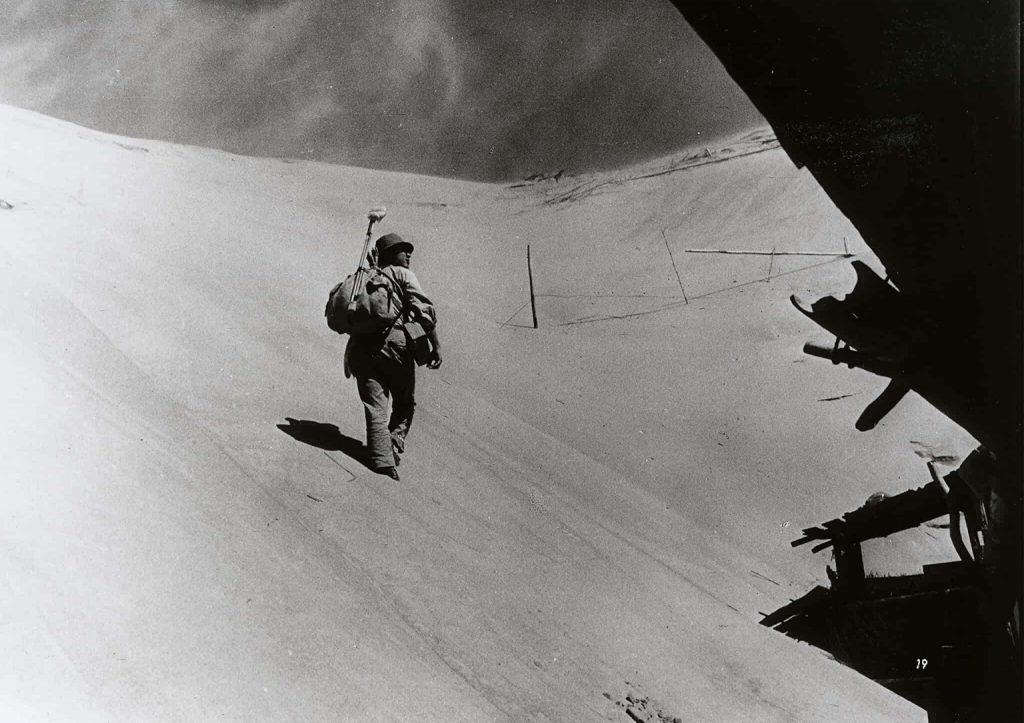

The second element is the sand. It pervades every scene, probably every frame. Hiroshi Segawa’s cinematography is stunning and really captures the heat and dust of the first half of the film. We have extreme close-ups of the protagonists in which it’s impossible to tell if you are seeing the man’s stubble or sand sticking roughly to him. These shots are in contrast with the vast expanse of the dunes themselves where the sand is always moving, always falling, a character in its own right. Early in the film there is a shot of the woman sleeping naked, the curves of her body resembling the dunes that surround them.

I have seen Woman in the Dunes twice now and still can’t put my finger on what exactly it’s meant to represent. The woman explains that ‘If we stop shovelling the house will get buried. If we get buried, the house next door is in danger’. We also know that the locals sell the sand as a cheap (and inferior) product to the construction industry, but why the sand can’t be collected in an easier way, we aren’t told. If this film was about reality, the locals would descend into the pits every day to collect the sand, instead of having someone live there. Neither are we told of how many others are living in these pits. No explanation is ever given. This is not a film about reality after all. I doubt that sand can be piled up at such steep angles without falling down and refilling the hole, but the images of the teacher desperately trying to climb out of the pit are beautiful and tragic. He is a beetle fighting a losing battle against gravity and a countless number of tiny grains – a battle he is doomed to lose.

It’s obvious that it’s an allegory of some kind. I’ve read elsewhere that it’s about the Japanese sense of duty – the man soon develops a kinship and a loyalty for the pit, the woman and the job of shovelling sand; but it could as easily be read as a study of Stockholm Syndrome (where someone who has been held captive begins identifying with their captors). After my first viewing I thought it could possibly be about the stages of a man’s life: the film begins with the man in the role of a child, helpless and entirely dependent on the woman, then becomes the rebellious teenager, until finally accepting and embracing his adulthood and his sexuality.

I was also reminded of the Laurel and Hardy great The Music Box, in which the two heroes continually attempt to carry a large piano up a flight of steps only for it to fall repeatedly to the bottom again. The comedy in The Music Box comes from the simple fact that the protagonists are incompetent (it is a comedy after all); in Woman in the Dunes it’s not a piano but the endless shovelling of sand, and the comedy has become a tragedy.

Although a little on the long side (2 hours 26 minutes), it never fails to keep your attention. Both Eiji Okada and Kyôko Kishida are fantastic, and their performances feel real and truthful. Okada commands the screen and it’s in him that we see ourselves, but Kyôko is excellent as the lonely woman, doomed to a thankless and dangerous task whilst coping with an intense sense of loss. Hiroshi Teshigahara’ direction is splendid, and there are some truly wonderful images throughout. Woman in the Dunes is a mesmerising film that grips you from start to finish. It doesn’t matter that the story is so odd and that its meaning is ambiguous, it simply must be watched. It’s exciting and horrific at times, as well as genuinely moving. One thing is for sure, you won’t look at sand the same way ever again.

Film ‘89 Verdict – 9/10