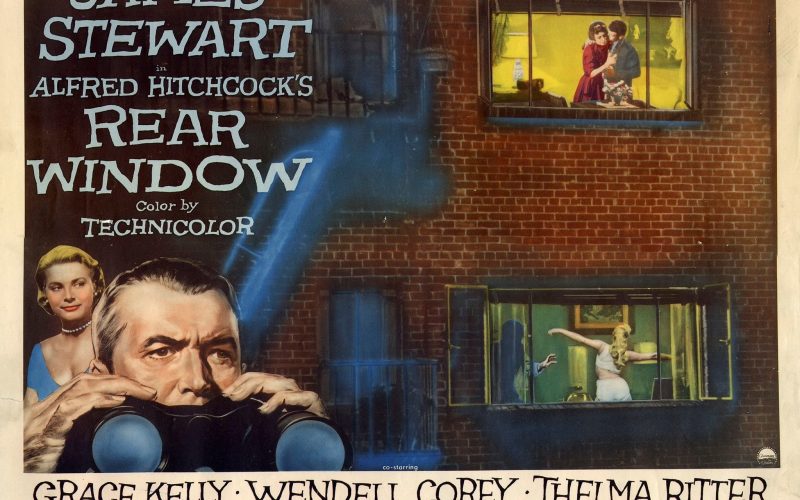

Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954).

Spies like us.

*** SPOILER ALERT ***

By the time of Rear Window’s release in September of 1954, the master of suspense, Alfred Hitchcock, had directed over 40 features and was very much in the tail end of his long and illustrious career in that he would only direct a further 13 theatrical films. Yet it is in this period, from the mid 1950’s onwards, where he was arguably at his most creatively successful and where he crafted many of his very best and most beloved works. Of those, Rear Window would undoubtedly both feature and place highly in the majority of top 10 lists of Hitchcock films by fans and critics alike.

Rear Window was made for an estimated $1 million and was shot entirely on one meticulously designed and crafted Paramount stage, the huge set consisting of dozens of apartments, several of which were completely furnished with their own running water and electricity. This wasn’t the first time that Hitchcock had used confined sets or locales having done so to great effect previously on Lifeboat (1944) and Rope (1948). The film centres around a wheelchair bound voyeuristic photographer who may or may not have discovered evidence of a grisly murder in one of the apartments across from his own.

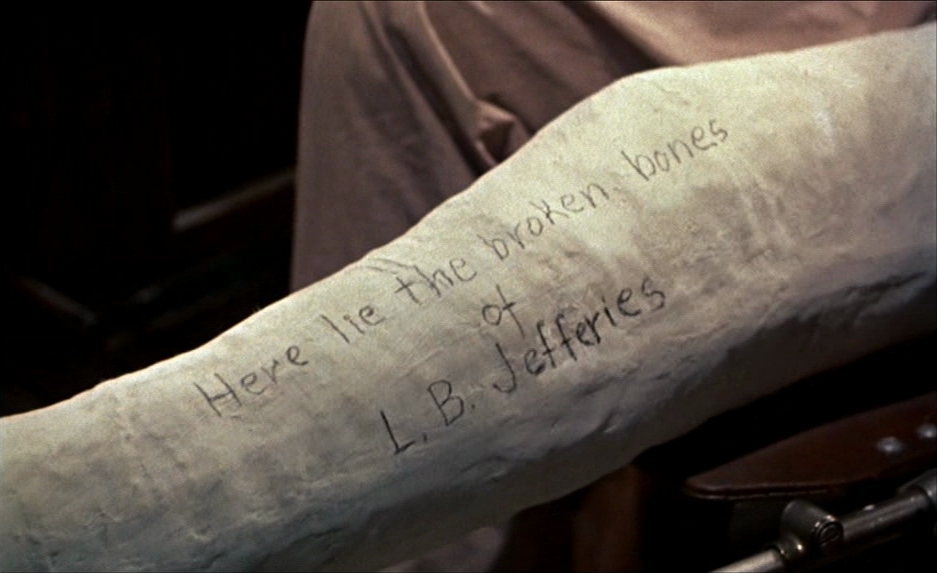

As the film opens it is not our protagonist L.B. Jeffries that is the voyeur but us, the viewer as the camera gives us the first glimpse into the lives of the inhabitants of the tenement block upon which Jeffries’ titular rear window looks. Whilst we peek into this colourfully mundane world and the humdrum daily activities of it’s inhabitants, Jeffries sleeps uncomfortably in the humid summer morning air. The camera shows us enough visual exposition to tell us that Jeffries has his left leg in full plaster cast up to the waist and is a photographer of some renown. This quick and efficient visual storytelling harks back to Hitchcock’s earlier work in the silent film era.

“We’ve become a race of peeping toms. What people oughta do is get outside their own house and look in for a change.”

So says Stella, Jeffries’ insurance company appointed nurse. It’s this focus on voyeurism – that which is forced through circumstance, that which is borne out of boredom and that which is done out of a belief that one has a duty to watch out for our common neighbour – which is displayed and explored in Rear Window. The very act of going to the movies is a form of voyeurism in and of itself albeit one laced with artifice as the lives we are watching aren’t real yet are often every bit as compelling, if not more so, than real life. In many ways, Rear Window’s nosey protagonist is a reflection of us, the audience, our confinement through choice to sit and watch others for hours on end is very much like Jeffries’ own situation. We are watching to be entertained and in many ways so is he yet with his curiosity comes a degree of interaction and ultimately of responsibility.

It is to his nurse Stella that Jeffries laments of his potential forthcoming marriage to Lisa Fremont whom he considers “too perfect” for him to marry. When Lisa is revealed to be played by Grace Kelly, arguably the most beautiful woman to ever grace the silver screen, Jeffries’ persona is laid bare for examination. What frustrations and insecurities must lie within a man, so driven and able on the surface, yet who would deny himself the very epitome of the perfect woman? What itch has he yet to scratch before he sees that he has everything he could ever want or need within his grasp?

“What is it about travelling from one place to another taking pictures? It’s like being a tourist on an endless vacation.”

The attentive viewer will be able to glean just enough from Jeffries’ initial conversation with Lisa so as to build a picture of his life outside of the constraints of his plaster cast. A rough and ready risk taker, traits that undoubtedly led to the racetrack photograph that caused the collision that in turn led to his injury. Jeffries seems far more interested in the eccentricities of his neighbours than his beautiful fiancé to be. In the six weeks since his accident has he done nothing more than watch from his two room apartment the lives of others seemingly less privileged than him? It would certainly appear so. Nowhere is this more obvious than when Jeffries observes the neighbour whom he mockingly calls “Miss Lonely Heart”, her tragic dinner date telling us in a brief moment all we need to know about her life as well as something about her unsympathetic observer. Miss Lonely Heart dines with a man who isn’t there whilst Lisa lovingly prepares a meal for Jeffries, a man who for her at times isn’t really there either.

Rear Window is peppered with several brief glimpses into the lives of characters whom we will never get to truly know throughout the film, only view from a distance. These are purely fringe characters, complex window dressing placed there to enrich and give life to the relatively confined environment. Never has a film so intimate in scope felt so satisfyingly rich in character detail and it’s Jeffries’ reaction to many of these observed little moments that enriches our view of him and the type of man he is. What is also so clever about Hitchcock’s meticulous story construction is how the actions and interactions of Jeffries’ neighbours often mirrors aspects of his own relationship with Lisa.

Rear Window has a script that bears such a great depth of characterisation that it is near flawless in its efficiency. Needless to say, such a confined story needs a great script and Rear Window’s is as good as any and certainly one of if not the very best scripts in a Hitchcock film. The exchanges of dialogue between the small core cast is precision writing of the highest order. No line is wasted or in any way superfluous to the requirements of the story being told.

What Hitchcock does in Rear Window that is so simple yet so fiendishly brilliant is to tap into our desire to spy on the lives of others no matter how trivial their day-to-day existence may be. The modern proliferation of reality TV programmes shows this to be a true human trait and it shows just how ahead of the curve the auteur director was over 6 decades ago.

“A murderer would never parade his crime in front of an open window.”

It’s when Jeffries and Lisa part on ill terms following a brief spat that he hears a scream that may or may not be the initiating sound of an event that will push his curiosity to consume him from this point on. The next day Jeffries sees a neighbour whom he calls “The Salesman” (Raymond Burr) wrapping large butchers knives in newspaper and from this point Jeffries begins to make the connection with The Salesman’s odd nocturnal activities and the scream he heard the night before.

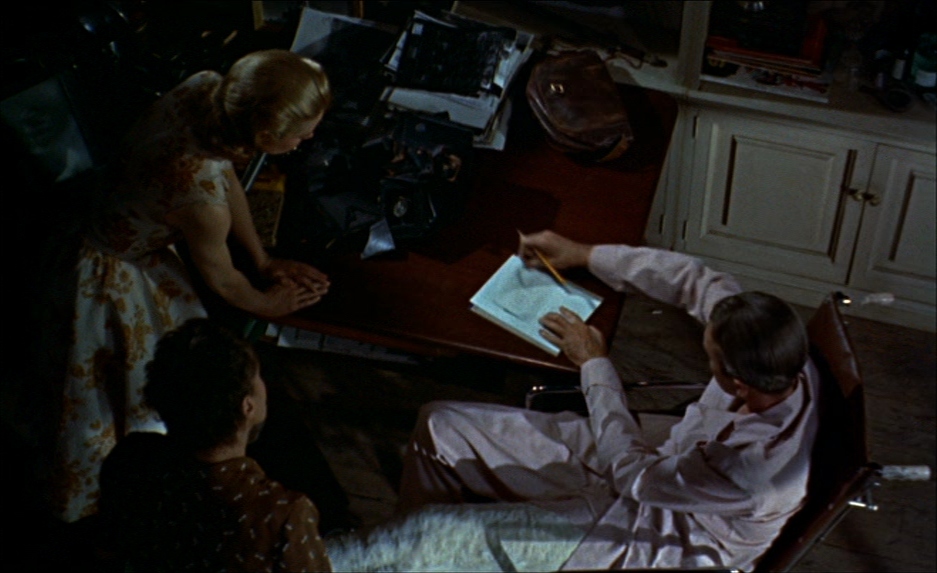

Jeffries’ suspicions as to the domestic murder that may have taken place mere yards from his home is shared with not just Lisa but also his policeman friend Lt. Tom Doyle. Doyle is initially sold enough on Jeffries’ idea to begin his investigation but later, having found no firm leads, claims Jeffries’ evidence to be nothing more than the ill-found suspicions of a man with far too much time on his hands. It’s left to Lisa to remain Jeffries’ only ally in his quest for the truth and she more than lives up to her image of the perfect companion as she serves as the investigative sleuth that Jeffries’ injury prevents him from being. In many ways she is the true hero of the story, loyal to Jeffries yet almost resistant to his inadequacies. It is Lisa who puts herself in harms way to attempt to uncover firmer evidence of the foul play that Jeffries so firmly suspects. Is Lisa more fittingly Rear Window’s protagonist than Jeffries who in many ways is more of an extension of us, the audience?

The exquisite use of a silent phone call near the end ratchets the tension up to eleven as things come to a head and with Jeffries’ allies otherwise engaged, he is left to face his neighbour alone. Unlike some of Hitchcock’s more abrupt endings Rear Window has a satisfyingly subdued yet unashamedly upbeat denouement that rounds things off perfectly. Indeed perfection is something that seems to permeate much of Rear Window. The simplistic brilliance of the central conceit of a confident, globetrotting photographer confined to his apartment; that same character so blatantly dismissive of the perfect woman he has at his beckon call; the set, so effective and efficient in its use yet it never fails to hold our interest due to the finely crafted people that populate it tapping into our inherent desire to observe the lives of others; the perfect cast, James Stewart, Grace Kelly, arguably the ultimate male and female Hollywood darlings whose chemistry here is something truly magical to behold.

One particular technical flourish of Hitch’s that can’t go unnoticed here is the use of a diagetic soundtrack as opposed to a traditional score. All the sound and music in Rear Window comes from within the film itself, from the various apartments and surrounding environment and adds subtly but immeasurably to Rear Window’s much needed sense of verisimilitude. It’s a bold and brilliant choice by a director at the very top of his game.

Revered filmmaker Peter Bogdanovich once described Rear Window as being Hitchcock’s “Testament film, the best example of what Hitchcock’s cinema at its best stood for which was essentially the use of the subjective point of view” and it would be hard to argue with that appraisal.

Alfred Hitchcock may well have peaked with Rear Window, then again there are one or two movies we’ve yet to cover from the intervening years that could be considered equally strong entries in his filmography. Maybe it’s too early to call a winner yet as to which is the auteur’s best work but Rear Window is nevertheless an undisputed classic of cinema and gets my absolute highest recommendation.

Film ‘89 Verdict – 10/10