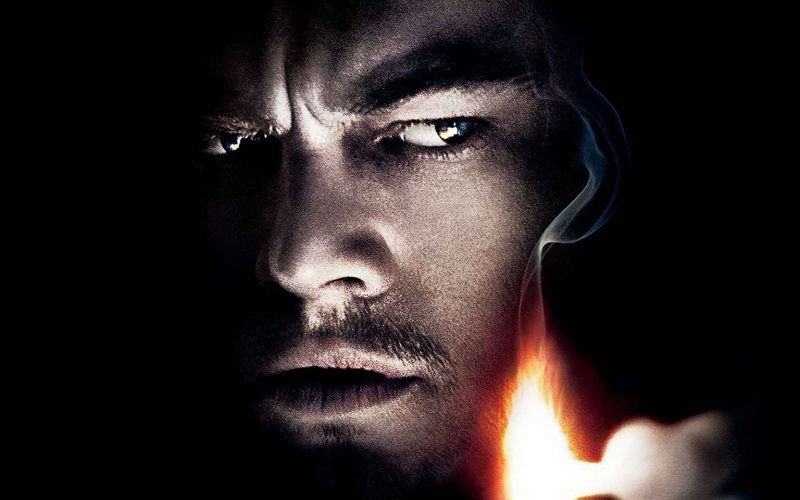

Shutter Island (2010).

Although known for making what may be considered ‘prestige’ films and the promotion of art-house classics, Martin Scorsese has always had a liking for more low-brow genre films, including the film noir ‘B’ pictures of the 1940s directed by the likes of Nicholas Ray and Ida Lupino. He hasn’t often dipped his toes into this genre as a filmmaker, except for two violent and highly stylised movies, Cape Fear (1991) and Shutter Island (2010).

Like Casino, Goodfellas and The Age Of Innocence, Shutter Island was based on a novel. Written by Dennis Lehane, it tells the story of a US Marshal, Edward ‘Teddy’ Daniels, who, with his partner Chuck Aule, travel to Ashcliffe Hospital for the criminally insane, located in Boston Harbour on Shutter Island. They’re there to investigate the disappearance of an inmate, Rachel Solando.

Immediately things are not as they should be – there seems to be a lack of trust from the staff who seem willing to offer only limited assistance. The patients seem to know more than the cops, one of them going so far as to grab Daniels’ notebook and scribble the word ‘Run!’ on one of its pages. He also finds some cryptic clues in the form of a note in Solando’s room – ‘The law of 4: Who is 67?’

The investigation takes place during a massive storm which limits their opportunities to interrogate the witnesses and the clues further. On top of this, Daniels beginnings to suffer debilitating migraines which cause him to pass out on a number of occasions. If this isn’t enough, the doctors in charge of the hospital, Dr John Cawley (Ben Kinsley) and Dr Jeremiah Naehring (Max Von Sydow) seem to be holding something back. There is something going on, something just beyond the reach of the lead detective that pushes his paranoia and neuroses to the fore.

The missing patient is soon found but things still don’t sit well with Daniels, there seems to be something happening just beyond his grasp. Furthermore, he has an agenda of his own. He’s not just on the island for the assigned case, he’s also there to find the man who killed his wife Delores (Michelle Williams) who he’s convinced is being kept in the mysterious Ward C, the building where the most dangerous of the inmates are being kept.

It may be obvious from the above description that Shutter Island is steeped in paranoia. From the opening scene on the ferry where a seasick Daniels spends most of his time throwing up, there is a pervasive sense of unease which clouds not just Daniels’ judgement but the viewers’ too. This unease is not just from the mystery, but also from the sense – like Daniels on the ferry – that we are not on solid ground, that we should question everything and then when answers are presented, we should perhaps question them too.

We know that Scorsese is indebted to the masters that came before him, and in the case of Shutter Island, he is undoubtedly standing on the shoulders of Alfred Hitchcock. The atmosphere, which almost drips off the screen and soaks our shoes, is reminiscent of Vertigo with more than a pinch of Psycho. If it were to be compared with the work of a modern master, I would suggest Brian De Palma, although Scorsese is more interested in the slow collapse of a mind and steers away from that director’s preference towards a sexual, psychoanalytical approach.

Daniels is a scarred individual, someone who has seen and experienced the very worst of mankind. He was there at the liberation of Dachau and witnessed the suffering of those he was freeing. He also took part in a horrific act of revenge against those who worked at the concentration camp. On top of this, he had to experience the loss of his wife and, from the start of the film, he is a very fragile individual on the verge of collapse.

The key to the film is Leonardo DiCaprio’s performance. DiCaprio has always been a very physical performer and here he’s no different. His inner turmoil is given a most expressionistic outward display, writ large in his sweaty face and bloodshot eyes. He hunches over, often barely able to stand, his hands often held to his face. This is in total contrast to the others around him who all seem to have a level of control he lacks.

As you would expect from a Scorsese film, the production values are superb but I would single out the cinematography by Robert Richardson and the music arrangement by Robbie Robertson. Richardson gives the landscapes an artificial quality, further adding to the sense that things are not as they seem. The sea is wild and foreboding, the island is dangerous, and the interiors, especially the luxurious doctors’ lounge and the corridors of Ward C, seem too hot, too claustrophobic, too anxious.

Robertson, who Scorsese has had a long relationship with (Robertson was a member of The Band whom Scorsese made the documentary The Last Waltz about), didn’t write a score for Shutter Island. Instead he found some of the most expressionistic modern classical music and used it in lieu of a traditional score. One standout theme is ‘Symphony No. 3: Passacaglia – Allegro Moderato’ by Krzysztof Penderecki, a piece full of uncertainty and deep resonating dread. It’s a superb piece that could work for just about any haunted house film, and fits so easily you could swear it was written for the film.

There are a lot of twists and turns in Shutter Island which I won’t go into now. Part of the pleasure of the film is guessing what will happen next. Although in terms of box office, it was one of Scorsese’s biggest hits grossing almost $300 million worldwide and, at the time of writing, has an IMDB user score of 8.1/10, it never really established a reputation that could endure. This I believe makes it ripe for rediscovery. Unfortunately I had read the book a few years before the film’s release so the ending of the film held no surprises for me. Normally I prefer reading the book before the film adaptation is made and often, like the anticipation of a novel, I have enjoyed getting the full movie treatment, however, in this case, I wish I hadn’t. But while that first viewing was compromised for me somewhat, I’ve found subsequent viewings to be surprisingly rewarding, unburdened from that initial sense of expectancy. Now I can appreciate the photography and the craftsmanship that went into making this damn fine film.

Whilst Shutter Island isn’t top-tier Scorsese, like Cape Fear before it, this is a fantastically engineered genre film made by a master craftsman who knows cinema inside out. From a cinephile’s perspective, there’s a lot to enjoy and appreciate here, and if you haven’t seen Shutter Island, this is a great opportunity to disengage your mind for two hours and enter a labyrinthine mystery that keeps you guessing. Many genre films of this particular type have been compared to a rollercoaster, but Shutter Island is more akin to a funhouse, a ride that can literally swipe the carpet from under you. It may not be the most pleasant of rides – good thrillers and horrors rarely are – but if you can stomach the sea-sickness and the sense of unease, there is a great time to be had here.

Film ‘89 Verdict – 8/10