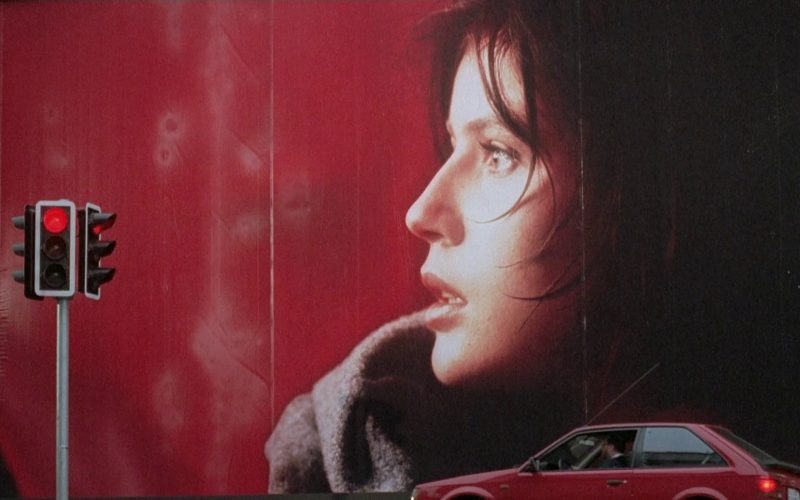

Three Colors: Red (1994).

Valentine is a model, living alone in a small apartment. By day she works and does ballet to keep fit. At night she pines after Michel, her distant, paranoid and controlling lover who travels Europe. She is lonely and consoles herself by sleeping with Michel’s jacket. One day she runs over a dog and takes him back to its owner who doesn’t seem very interested in his dog’s plight. She doesn’t know quite what to think of this man until she discovers he spends his time spying in on his neighbour’s phone calls. He knows it’s illegal, he is, after all, a retired judge, but he does it because he too is lonely. Valentine is at first disgusted, however, as the film progresses, a mutual friendship is slowly developed.

This may seem like a simple story, however this is a Krzysztof Kieslowski film and Kieslowski is a filmmaker who uses simplicity as a coat-hanger, something on which to hang his ideas and to play with the audience’s expectations.

In Red, the third of his Three Colors films, Kieslowski gives himself one simple problem; how do you tell a story about two different people of two different generations without the use of flashbacks or scenes of long expository dialogue?

The answer is to bring the two different timelines together as one and to make random coincidence completely acceptable. This is the essence of Red. All three films of the trilogy are interested in form: Blue explores internal grief and makes it very cinematic – in effect interpreting the internal life, thoughts and emotions, using the language of film; White challenges the constraints of comedy, whilst Red tackles the storytelling process itself.

At first glance, it’s easier to understand how Red relates to the third element of the French motto – liberty, equality, fraternity. Whereas, Blue and Red’s examination of Liberty and Equality were rather opaque, the central premise of Red is, undoubtedly, one of Friendship. Valentine and the Judge do grow to like each other, overcoming each other’s self-erected boundaries, and therefore becoming close.

To Valentine, the Judge represents the future, one in which she hopes to be happily married. He tells her of a dream he has where she wakes up, middle aged and smiling. Valentine accepts this, not simply as a dream, but as prophesy. She so desperately wants it that she fully accepts it as her future. For the Judge, this is also a future he hopes will come to pass, however, there’s something else – he hopes for Valentine a life he was never able to experience.

Throughout the film, Valentine crosses paths with Auguste, a student studying to be a judge himself. They don’t speak but they’re aware of each other as they live in the same street. They absently watch each other from their apartment windows, not spying, just aware as neighbours often are. They pass each other in the street, not aware of each other. In one scene they’re both in a music shop, listening to the music from headphones hanging down for the customer’s convenience. It’s almost as if they’re together without ever knowing it. There also seems to be a playful sense of inevitability.

What Valentine doesn’t realise is that one of the conversations she overhears at the Judge’s house is Auguste and his girlfriend. After Valentine insists, the judge gives himself in to the authorities, admitting to spying. As a result of this Auguste’s girlfriend meets another man and, after catching them together Auguste is devastated. He sinks into a depression and it looks like he may never recover.

But who is Auguste? Why are we being told his story? In many respects we aren’t being told his story and this is the answer to Kieslowski’s conundrum: how do you tell the story of the old Judge’s past without the use of flashback or expository speeches. Auguste is actually living a version of the Judge’s past. Even before the Judge tells his story to Valentine, we have already seen it, the loss, the tragedy and the loneliness. How does this tie into Valentine’s story and what will happen to Auguste? This is the motivation – will the younger version of the Judge be destined to complete his story in the same way it had with the older one? Or will there be another, happier ending which may or not involve Valentine?

Three Colors: Red marks the end of a remarkable trilogy. I didn’t think Blue could have been bettered but Red is at the very least its equal. The performances are perfect, both Irène Jacob as Valentine and Jean-Louis Trintignant as the retired Judge are spot on. Throughout Kieslowski paints the screen in vivid reds which are quite beautiful to look at and his handling on the various intertwining and overlapping stories is succinct and precise.

If there is one distraction it’s the cameo’s of the main character’s from Blue and White. We know they’re coming and we anticipate their appearance. Alfred Hitchcock used to make his cameo early in the film so as not to distract the audience, Kieslowski waits until the very end, but when it comes, distraction or not, it’s certainly worth it – tying up the three stories without compromising the integrity of the series.

The trilogy is now over 20 years old yet it remains a remarkable achievement. Kieslowski admitted that the overriding principles of France, the three doctrines liberty, equality and fraternity were used solely to get funding to make the films, however, there is no doubt that these principles are central to the director’s story-telling and reveal things that may not necessarily have been obvious.

Although each film – Blue, White and Red – are very different in story, mise en scene and of course, cinematography – they still work remarkably well as a coherent series. What Kieslowski achieved with these three films is remarkable and still resonates two and a half decades later.

Film ‘89 Verdict – 10/10

The Three Colors Trilogy – Blue, White, Red – are currently available to stream on Amazon Prime Video.